Public choice. Public choice - abstract Publicly collective choice in a market economy

Public choice theory has become one of the main areas of research related to the use of the methodology of neoclassical analysis in relation to the institutional system. It originated in the 1960s as a branch of economics that studies taxation and government spending in the context of providing social benefits. Subsequently, its boundaries have expanded significantly and at present it is interpreted as theory of economic policy.

The representatives of the Italian school of public finance of the late 19th century are considered to be the forerunners of the theory of public choice. Pantaleoni, Mazzola, de Witti and others, Swedish researchers of the early 20th century. Wiksel and Lindahl, who prioritized political processes that would ensure the definition of state budgetary policy. The emergence of the term "public choice" is associated with the publications in 1948 by the Scottish economist Black on the rule of the majority.

A direct impetus to its development was given by the studies of the 1930s and 1940s by such well-known researchers as Bergson, J. Schumpeter, Samuelson, who developed the concept of welfare economics. And the American researcher Buchanan is rightly considered the founder of the theory of public choice. Arrow also made a great contribution to its development.

James Buchanan

James McGill Buchanan (b. 1919) graduated from the College of Education, then the University of Tennessee. During World War II, he fought the Japanese in the Pacific. After demobilization, he studied economics at the University of Chicago under the guidance of F. Knight, where in 1948 he received his doctorate. In 1950 he became a professor of economics at the University of Tennessee, then dean of the economics department at the University of Florida, and also worked at the University of Virginia.

In 1957, Buchanan founded the Thomas Jefferson Center for Political Economy Research, and in 1969 the Center for the Study of Public Choice at George Mason University (Virginia). Buchanan is the author of many works: "Theory of pressure and political economy" (I960), "Formula of Consent: The Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy" (1962), "Cost and Choice: Political Applications of Economics" (1972), "Limits of Freedom: Between Anarchy and Leviathan" (1975), "Democracy in short supply" (1977), "The Power of Taxes" (1980), "Freedom, the Market and the State: Political Economy in the 1980s" (1985), "The Political Economy of the Welfare State" (1988) and many others.

In his works, he considered the problems of the theory of "public choice", democracy in the conditions of a budget deficit, the political and legal foundations of the theory of decision making. In 1986, he received the Nobel Prize "for developing the theory of decision-making in the fields of economics and politics, as well as political theories that demonstrate the limited role of government in the economy."

Buchanan at creation public choice theory became the first researcher who chose a completely new direction of economic analysis - non-market solutions, which closely connected him with the neo-institutional direction. His first work on this topic "Pure Public Finance Theory: A Proposed Approach" was published in 1949.

The study of "public choice" was concentrated at the University of Virginia, where in 1969 Buchanan and Tulloch created Center for the Study of Public Choice, which has become the nucleus virgin school political economy. The hallmark of the school was the application of the methods of mathematical analysis to non-traditional areas of study, primarily politics. On this subject, Buchanan wrote: "Public choice is a view of politics that arises from the extension of the application of the tools and methods of the economist to collective or non-market relations." In this regard, the theory of public choice has today another name - new political economy.

According to Buchanan, the theory of public choice follows from two methodological assumptions. The first is that each individual pursues his own interests, that is, according to A. Smith, "an economic man" and selfish; the second is the interpretation of the political process by which "economic man" realizes his interests through the process of exchange. To comprehend the political process as a mutually beneficial exchange for a "man economically" allows individualism, which is of crucial importance in public choice theory.

Thus, the researcher singled out three most important elements on which the theory of public choice is based:

Methodological individualism;

the concept of "economic man";

The concept of politics as an exchange.

The ideal political institutions and processes are those that, like competitive market, allow to pursue individual interests, at the same time ensuring public interests.

Buchanan emphasizes that the interests of individuals in public choice are individual and public goods with externalities, the provision of which through the market turns out to be less efficient according to the Pareto law than due to one or another political process (certain actions of the state). At the same time, the researcher considers the state primarily as a means of implementing social consent, developing rules that ensure social interaction for the benefit of everyone, and not as a simple supplier of social benefits and a corrector of "failures" in the market.

Approach to politics as a mutually beneficial exchange does not mean that there is no difference between the political market and the market for private goods. Buchanan argues that the efficiency of the private goods market increases with an increase in the level of competition, that is, an increase in the number of its participants, and the political market loses its efficiency from an increase in participants. Any political decision will be Pareto efficient when no one objects to it, but as the number of participants in the process grows, the probability of unanimity inexorably approaches zero.

Considering the differences between the markets for individual (consumer market) and social goods (political market), Buchanan introduces the concept of "quality of choice". He proves that the "quality of choice" in the consumer market is almost imperceptible, since people are always sure that they will receive the purchased good. On it, the buyer can choose between many varieties of one good, buy different goods in a variety of variations.

In the political market for social benefits, everything is more complicated, because when voting for a candidate who promises to increase pensions and repair roads, these benefits are not guaranteed even if this candidate wins the elections. Therefore, the political choice is made from a very limited set of mutually exclusive alternatives. From this, Buchanan concludes that the private market should be preferred over the state wherever possible.

However, what to do in a situation where the private market is extremely inefficient? An American scientist proposed a theory for this case "constitutional economics" which requires the fulfillment of two conditions:

All individuals must be parties to the same contract (agreement). Such a social agreement was defined as a "constitution", that is, a basic agreement;

This transaction by all individuals must be unanimous.

If agreement in a society on a "constitutional agreement" is not reached or violated, then such a society will be threatened with anarchy. And the fear of chaos also influences the individual's decision to adhere to constitutional rules.

In the case where there is no unanimity of the political decision, two problems arise, firstly, some members of society will be forced to act contrary to their interests; secondly, a kind of "infinite regression" arises, that is, a return to the initial state with attempts to achieve unanimity (defining the rules for voting, re-voting, recounting, etc.).

Buchanan sees a fundamental difference between the two stages of the political process: making rules (constitutional) and playing with them (post-constitutional). Accordingly, the functions and role of the state differ, according to which the researcher singles out "manufacturing state" (provides society with non-market social benefits) and "protector state" (ensures the game according to the constitutional rules). The ideal social system, according to the scientist, meets the following requirements:

The same approach to all at the constitutional stage. At the same time, the rule of unanimity serves to protect individual rights and ensure full equality;

Actions at the post-constitutional stage of the political process are effectively limited by the rules that are developed at the constitutional stage. This applies to everyone, both ordinary citizens and those elected by the people to all government bodies;

There is a fundamental difference between actions carried out within the framework of constitutional rules and changes to these rules themselves. Changes are possible only on a constitutional basis and are ideally built on unanimity.

In Buchanan's view, to the extent that a country meets these three requirements, it can be considered constitutional democracy, whose institutions have the normative qualities inherent in contractionism.

In his Nobel lecture, Buchanan succinctly reflected his creative credo: "In my fundamental convictions, I remain an individualist, constitutionalist, contractionist, democrat (all these words, in fact, mean the same thing to me), and professionally I am an economist" .

Kenneth Arrow

A research economist who is rightly considered to be a mass attitude to public choice theory Kenneth Arrow(born 1921), Nobel laureate 1972. It was he, together with the Scot Black, who first tried to apply the methods of economic analysis to political processes. In his work "Social Choice and Individual Values"(1951), which at one time caused a great resonance, drew an analogy between the state and the individual and denied the main conclusions of public choice theory regarding the economic role of the state.

Arrow was born in New York, graduated from the local City College, and later from Columbia University. He took part in the Second World War, after which he worked as a professor of economics at Stanford (California) and Harvard Universities.

Arrow is best known as a critic of the "public choice" idea. In the named work, he deduced "Arrow's theorem", in which he proves the impossibility of a society making a "collective" decision about its own priorities, taking into account individual priorities.

The scientist's research is devoted economic development, problems of distribution and relations between the market and the state. Among his scientific achievements is a model of general economic equilibrium, built by him together with Zhe. Debre; theory of optimal reserves (accumulation); the theory of uncertainty (decision making in a situation of incomplete information).

Among the works of K. Arrow, in addition to the mentioned book, it is also necessary to highlight "Existence of Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy" (1954), "Replacement of capital by labor and economic efficiency" (1961), "Public Investments, Rates of Return and Optimal Tax Policy" (1970), "Essays on risk theory" (1971), "Resource Allocation Studies" (1977), "Limits of Organization"(1974) and some others.

Kenneth Arrow received the Nobel Prize in Economics jointly with J. Hicks "for their pioneering contributions to the general theory of equilibrium and the theory of welfare."

The founder of this another important component of neo-institutionalism is James Buchanan (1919), who expressed in terms of economic science the main patterns of political decision-making.

Major works: "The Pure Theory of Public Finance" (1949), "Individual Voting Choice and the Market" (1954), "Consent Calculation. The Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy” (1962 together with G. Tulloch), “Public Finance in the Democratic Process” (1967), “The Limits of Freedom. Between Anarchy and Leviathan” (1975), “Democracy in Deficit” (1978, together with R. Wagner), “The Power of Taxation” (1980, together with J. Brennen), etc.

Buchanan, like other representatives of neo-institutionalism, used the economic theory of the neoclassicists as tools of analysis. According to J. Buchanan, this is quite legitimate, since the methods of analyzing market behavior can be applied to the study of any field of activity, including politics, because everywhere people are guided by the same motives. So, in politics they are not driven by altruistic or moral inclinations. Political decisions are the choice of alternatives, and the achievement of political agreement is similar to how it happens in a normal market. The peculiarities of the political market are that if in the ordinary market people exchange money for goods (or product for product), then in politics they pay taxes in exchange for public goods. But although the consumer of public goods is not an individual, but society as a whole, nevertheless, in politics, according to Buchanan, there is still an analogue of free trade. This is the agreement between people inherent in any kind of exchange. In his opinion, the unanimity achieved by the participants in the collective choice in politics is analogous to the voluntary exchange of individual goods in the market.

This is the essence of the economic approach to collective activity. Here, the thesis is called into question that the desire to obtain benefits clearly dominates in the economic sphere, and in the political sphere, supposedly, people do not seek to maximize their utility, but try to realize the public interest, or the common good.

According to Buchanan, a person maximizes utility, both in market and in political exchange (political activity is considered by him as a special form of exchange). In economics, as in politics, people pursue similar goals - to gain benefits, profits. In making appropriate decisions, politicians, according to Buchanan, proceed from their private interests, which do not always correspond to the interests of society. Politicians are thinking about how to ensure success in elections, get votes. The most popular measure is to increase government spending. But this stimulates inflation. This is followed by the strengthening of strict regulation, state control, inflation of the bureaucratic apparatus. As a result, the government concentrates more and more power in its hands. And the economy is on the losing end.

Thus, the myth of the state, which has no other goals than caring for the public interest, is exposed. The state is people who use government institutions for their own interests. The state is an arena of people's competition for influence on decision-making, for access to the distribution of resources, for places in the hierarchical ladder.

The solution to the problem of the abuse of political power, according to Buchanan, lies in the development of the concept of organizing the political market. He proposes to reform political procedures and rules in such a way that they contribute to the achievement of general agreement. In this ideal case, mutual benefits are expected from all parties as a result of collective action, similar to what happens in the market.

In Buchanan's concept, two levels of public choice are distinguished within the framework of political exchange. The first level is the development of rules and procedures for the political game. The second is the formation of a strategy for the behavior of individuals within the framework of established rules.

At the first stage, the rights of individuals are determined, the rules of relationships between them are established. In public choice theory, this is called constitutional choice. The constitution is the key category of J. Buchanan's concept. The term "constitution" refers to a set of pre-agreed rules by which subsequent actions are carried out. For example, the rules governing the ways of financing the budget, the approval of state laws, the taxation system, etc. The current policy is the result of a game within the framework of constitutional rules. And just as the rules of the game predetermine its probable outcome, constitutional norms shape the results of a policy or, conversely, make it difficult to achieve them. Therefore, the effectiveness and efficiency of policy depends to a large extent on how well the original constitution, or, as Buchanan calls it, the constitution of economic policy, was drafted.

But here the most difficult problem arises - the development of rules according to which this constitution is adopted, the so-called pre-constitutional rules. Viewing politics as a process of complex mutually beneficial exchange, Buchanan proposes to organize this exchange in such a way that all participants can expect to receive a net positive result at the level of constitutional choice. J. Buchanan considers this issue from the standpoint of individual members of society who are faced with the choice of alternative rules and decision-making procedures and who know that later they will act within the framework of these rules.

When solving this problem, J. Buchanan puts forward the rule of unanimity for the adoption of the original constitution, since the principle of a qualified and even more so simple majority, even in a direct democracy, can lead to infringement of the rights of the minority. Needless to say, how high the costs of decision-making in conditions of unanimity. The principle of a simple majority allows the choice in favor of an economically inefficient result.

More the situation is more difficult in a representative democracy, when the public choice is carried out at certain intervals and is limited to the circle of applicants who offer their own package of programs. Voters cannot afford the significant expenses associated with obtaining the necessary information about the upcoming elections. There is a kind of threshold effect - the minimum value of benefit that must be exceeded in order for the voter to participate in the political process. A rational voter must balance the marginal benefits of influencing a deputy against the marginal costs. As a rule, the latter are much higher than the former, so the voter's desire to constantly influence the deputy is minimal.

The situation is quite different for voters whose interests are concentrated on certain issues (for example, manufacturers of certain goods). By creating groups, they can significantly offset the costs if the bill that suits them is passed. The fact is that the benefits from the adoption of the law will be realized within the group, and the costs will be distributed to the whole society as a whole. It can be said that the concentrated interest of the few wins over the scattered interests of the majority. The situation is aggravated by the interest of deputies in the active support of influential voters, because this increases the chances of their re-election for a new term. And this is a significant flaw in representative democracy, because in a direct democracy, decisions that are beneficial to them would not be made.

Thus, as Buchanan argues, the omnipotent democratic government, precisely because of the unlimitedness of its power, becomes a plaything in the hands of organized interests, for it must please them in order to secure a majority.

One area of research in public choice theory is the economics of bureaucracy. The economy of bureaucracy, according to public choice theory, is a system of organizations that satisfies two criteria: it does not produce economic benefits and it derives part of its income from sources not related to the sale of the results of its activities. In this regard, the theory of political rent is of interest. Political rent seeking is the pursuit of economic rent through the political process. Politicians, although controlled by voters (because they are forced to consider re-election prospects, secure long-term party and public support for themselves), choose that solution from a set of acceptable alternatives, the execution of which maximizes their own utility, and not the utility of its voters. This choice is one of the main motivations of politicians. In the broad sense of the word, this is their “political income”.

In addition, policy makers are interested in solutions that provide clear and immediate benefits and require hidden, hard to define costs. Such decisions contribute to the growth of the popularity of politicians, but, as a rule, they are not economically efficient.

The described abuses of the bureaucracy cannot be fought by the forces of the state itself. The hierarchical structure of the state apparatus is built on the same lines as the structure of large corporations. However, public institutions are often unable to take advantage of the organizational structure of private firms. The reasons are weak control over their functioning, insufficient competition, and greater independence of the bureaucracy. Therefore, Buchanan and his followers are in favor of limiting the economic functions of the state in every possible way.

Even the production of public goods is not a reason, from their point of view, for government intervention in the economy, since different taxpayers benefit differently from government programs. In their opinion, it is democratic to transform public goods and services into economic goods produced by the market.

The merit of the theory of public choice is the formulation of the question of the failures of the state (government). Failures (fiasco) of the state are cases when the state is not able to ensure the effective distribution and use of public resources.

Typically, the failures of the state include:

1. Limited information necessary for decision-making.

Just as there can be asymmetric information in the marketplace, government decisions can often be made without reliable statistics to make better decisions. Moreover, the presence of powerful groups with special interests, an active lobby, a powerful bureaucratic apparatus lead to a significant distortion of even the available information.

2. Imperfection of the political process. Rational ignorance, lobbying, manipulation of votes due to imperfection of the regulations, logrolling, etc.

3. The state's inability to fully foresee and control the immediate and long-term consequences of its decisions. The fact is that economic agents often react in a way that the government did not expect. Their actions greatly change the meaning and direction of the actions taken by the government. Measures taken by the state, merging into the overall structure, often lead to consequences that differ from the original goals. Therefore, the ultimate goals of the state depend not only, but often not so much on itself.

The activity of the state, aimed at correcting the failures of the market, itself turns out to be far from perfect. The fiasco of the government is added to the fiasco of the market. Therefore, it is necessary to strictly monitor the consequences of its activities and adjust it depending on the socio-economic and political situation. When applying certain regulators, the government must strictly monitor the negative effects and take measures in advance to eliminate the negative consequences.

To correct the existing situation, according to supporters of the public choice theory, it is possible with the help of a constitutional revolution. Buchanan proceeds from the paramount importance of the formation of constitutional norms and rules. In this regard, Buchanan's substantiated distinction between two different functions of the state is important:

1. "State-guarantor".

2. "State of production".

The first is the result of an agreement between people and a kind of guarantor of their compliance with the constitutional treaty. Enforcing rights in society means jumping from anarchy to political organization.

The second characterizes the state as a producer of public goods. This function of the state arises as a kind of agreement between citizens regarding the satisfaction of their joint needs in a number of goods and services. Here lies the threat of the emergence of an autocratic state. It is the development and strengthening of the state-producer that leads to the strengthening of the influence of the bureaucracy. Buchanan and his supporters consider the reduction of the economic functions of the state and privatization to be a condition for an effective fight against bureaucracy. In their opinion, the state should perform protective functions and not take on the functions of participation in production activities.

Another achievement of the theory of economic choice is the introduction of the concept of the political-economic (political) cycle - the cycle of economic and political activity of the government between elections. Buchanan noticed that government activity between elections is subject to certain patterns. With a certain degree of conventionality, it can be described as follows.

After the election, a number of measures are taken to change the goals or scope of the previous government. These measures are especially radical if a party comes to power that was previously in opposition. Attempts are being made to reduce the state budget deficit and curb the unpopularity of programs. Newly come to power people are trying to fulfill at least part of the election promises. However, activity then declines until the fall in popularity of the new government reaches a critical level. With the approach next elections government activity is on the rise.

The theory of public choice has made a significant contribution to the development of problems of the role of the state and the political system as a whole, revealed the place and role of economic actors in making political decisions and developing the political system of society.

If we talk about neo-institutionalism in general, then the recognition of the merits of the new direction was expressed in the award Nobel Prize in economics to its most prominent representatives - James Buchanan (1986), Ronald Coase (1991), Gary Becker (1992) and Douglas.

Public choice theory is an important part of institutional economics, sometimes referred to as the "new political economy", because it studies the political mechanism of economic decision making. Having called into question the effectiveness of state intervention in the economy, representatives of the theory of public choice consider the process of making political decisions as an object of analysis.

Public Choice Theory- This is a branch of economic science that studies the patterns of choice of ways for government activities in the field of economics and how this choice is made under the pressure of a democratic system. Economics and politics in public choice theory interact with each other; the new political-economic approach considers not only the economic foundations of behavior in the political process, but also political methods of intervention in the market economy.

14.1. Methodology for public choice analysis.

The concept of "economic man".

methodological individualism. Politics as exchange

The study of public choice theory is based on public choice, which is a set of non-market decision-making processes regarding the production and distribution of public goods, which is usually carried out through a system of political institutions. If the market reveals the mechanisms of individual preferences regarding the production of private goods, then the state is an analogue of the market and reveals the preferences of individuals regarding the production of public goods. A feature of this mechanism for identifying preferences is its non-market nature.

J. Buchanan wrote: "Public choice is a view of politics that arises as a result of the extension of the application of the tools and methods of the economist to collective or non-market decisions."

James Buchanan

American economist James McGill Buchanan was born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. His father, James, after whom J. Buchanan was named, was a farmer, and his mother, Leela (née Scott) Buchanan, was a school teacher before marriage; J. Buchanan's parents were actively involved in local political life. Grandfather John P. Buchanan served one term as Governor of Tennessee; he was nominated for the position by the Populist Farmers' Union. His parents urged him to repeat the path traveled by his grandfather. However, the Great Depression thwarted plans to study law at Vanderbilt University. Instead, he enrolled at Middle Tennessee Teachers College in Murfreesboro, earning his tuition and books by milking cows.

He received his economic education at the University of Tennessee (MA, 1941) and the University of Chicago (Doctor, 1948). He has been a professor of economics at the University of Tennessee (since 1950), the University of Florida and the University of Virginia (since 1956), and has taught at other educational institutions. In recent years, he has worked at the Public Choice Research Center in Fairfax, Virginia.

The name of J. Buchanan is inextricably linked with the science of public choice. For a long time there was a belief that the decisions taken by individual politicians, political and state organizations should be aimed at bringing the greatest benefit to the whole society. K. Wixel in 1897 for the first time defined politics as a mutually beneficial interchange between citizens and public structures. Developing his ideas, J. Buchanan and G. Tulloch in 1962 published a book under a rather unusual title - "Consent Calculation". Their goal is to analyze the process of making economic decisions by mixed methods of economic and political sciences; the initial premise is directly opposite to the generally accepted one - the decisions of politicians and public organizations proceed, first of all, from their own interests. The main goal of politicians, for example, is to get the maximum vote in elections (as a result, before elections they often make unreasonable decisions from an economic point of view), and state bodies - to maximize their size and power. Here you can see an analogy with microeconomics, built on two fundamental assumptions: the consumer seeks to maximize utility, and the firm seeks to maximize profits. When analyzing the market, we operate with the concepts of supply and demand; in public choice, such opposites are groups of voters and lobbying organizations that differ in their goals and requirements, on the one hand, and politicians, on the other. As a result of their interaction concrete political decisions are born. Various decision-making procedures have also been explored, such as voting rules, as well as the structure of the legislatures themselves.

J. Buchanan in 1986 was awarded the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics "for the study of the contractual and constitutional foundations of the theory of economic and political decision making." The decision of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that "J. Buchanan's main achievement is that he constantly and persistently emphasized the importance of fundamental rules and applied the concept of the political system as an exchange process in order to achieve mutual benefit."

http://gallery.economicus.ru

The main areas of analysis in the theory of public choice are: the electoral process; activity of deputies; theory of bureaucracy; regulation policy and constitutional economics. An important role in their development was played by J. Buchanan, D. Muller, W. Niskanen, M. Olson, G. Tulloch, R. Tollison, F.A. Hayek and other scientists. By analogy with the market of perfect competition, they begin their analysis with direct democracy, then moving on to representative democracy as a limiting factor.

The problems of public choice theory can be formulated as a series of questions:

Is it possible to find a fair collective solution?

· How to "measure" the opinion of individual voters?

· How to influence fellow citizens to make the right decision?

· What are the goals of public welfare? In the interests of whom should society develop in the first place?

· Why do the interests of consumers prevail in verbal disputes, but the interests of producers control politics?

· How to create a coalition government? What are the reasons for the stability of coalitions?

· How do people benefit from the political process?

· Why does the law degenerate into arbitrariness? How to prevent the transformation of democracy into an authoritarian regime?

These questions show that, moving from the simple to the complex, it is possible to analyze various aspects of the modern political system by economic methods.

The main assumptions of public choice theory are:

methodological individualism;

the concept of economic man;

· Politics as an exchange.

Public choice theory is a special case of rational choice theory, which develops the concept methodological individualism, incorporated in the works of T. Hobbes, B. Mandeville, A. Fergusson, K. Menger. This concept consists in the fact that people acting in the political sphere strive to achieve their personal interests under the restrictions imposed by operating system political institutions.

A person in a market economy, identifying his preferences with a product, seeks to make decisions that maximize the value of the utility function, i.e. his behavior is rational. The formulation of the concept of "rationality" is considered not only in a strict form (maximization principle), but also taking into account the time limit, when people strive to provide a certain level of their needs and are guided in their activities, primarily by the economic principle, comparing marginal benefits and marginal costs. . Therefore, public choice theory is based on the concept of "economic man".

Another of the methodological approaches of the public choice theory is the approach to politics as a mutually beneficial exchange based on the analogy between the market for goods and the political market.

Politics as exchange

Politics is a complex system of exchange between individuals in which they collectively seek to achieve their private interests, since they cannot realize them through ordinary market exchange. There are no other interests, except for individual ones. In the market, people exchange apples for oranges, and in politics, they agree to pay taxes in exchange for the benefits that everyone and everyone needs: from the local fire department to the court.

Buchanan J. Constitution of economic policy //

Questions of Economics. - 1994. - No. 6. - S. 108.

In the market, people express their preferences in the consumption of goods as a buyer, forming the demand for goods and services, and consumers of public goods express their interests as voters through the voting mechanism. Vote- this is a peculiar form of taking into account individual preferences, in accordance with which the will of the participants is carried out.

Unlike private, public choice is carried out at certain intervals, limited by the circle of applicants, each of whom offers his own program. Voters are more limited in their choice than buyers of goods in the market, primarily in terms of the information they have.

Participants in the political process are also politicians and civil servants (administrators, officials, bureaucracy).

Politicians define development goals and means to achieve them, seek approval for the programs they have formulated and, if supported, seek ways to implement their programs. Politicians are a kind of entrepreneurs; however, they are interested in the demand for their products not from buyers, but from voters; in their activities there is not the principle of self-sufficiency, but the need for re-election; they maximize not profit, but prestige.

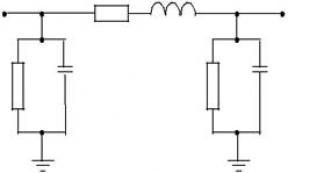

A politico-economic circuit is formed, similar to the circuit of goods and services, where households and firms are replaced by voters and politicians, and instead of markets for goods and resources, the political market and the market for public goods are used (Fig. 14.1).

In the simplest model, voters shape social preferences. In the political market, the most popular politicians are selected, to whom voters delegate their powers by voting. Politicians, in turn, legislate and organize the supply of public goods to voters.

Rice. 14.1.Political-economic circuit

This model can be complicated by the inclusion of bureaucrats (Figure 14.2). The term "bureaucracy" is used in the Weberian sense of the word - as a designation of the rational activity of professional civil servants. Voters who voted for politicians are directly subordinate to the bureaucrats. The behavior of bureaucrats is determined not only by legislators, but also by job descriptions, defining their rights and obligations, their minimum goal is to maintain their position, the maximum is to increase their status.

Rice. 14.2.Political-economic circuit with the participation of the bureaucracy

Thus, the main problem of public choice is the problem of rational behavior of voters, and lies in the fact that from the standpoint of an individual it is irrational to make significant efforts in order to extract information that contributes to a more rational public choice.

Spreading system methods research is accompanied by the development of economic and mathematical modeling. Public choice theory is dominated by statistical and econometric methods based primarily on positivism. The most widely developed econometric techniques are structural equation models, time series analysis, and non-linear estimates.

14.2. Model of interaction between politicians and voters.

Public choice under direct democracy.

Median voter model. public choice

in a representative democracy. The Voting Paradox

Unlike an authoritarian society in a democratic state, political decisions are evaluated and approved by the people, which takes place both directly in referendums and indirectly, through alternative elections. The main features of democracy are manifested in: participation in government; realization of constitutional freedoms; equality of opportunity for the development of each person.

Let us consider how public choice is carried out in conditions of direct and representative democracy. direct democracy- this is politic system in which every citizen has the right to personally vote for a political course or program.

With an increase in the number of voters and an increase in problems that require constant solution, direct democracy is impossible. There is a need for representative institutions and the selection of candidates for them. Representative Democracy is a political system in which citizens periodically elect representatives to elected bodies.

unanimity rule suggests that a certain alternative can be said to be preferred only if it is preferred by all individuals in the group. Thus, the decision is made only if all those participating in the voting vote for it. It is rather difficult to achieve such a solution, since the preferences of individuals differ from each other; as a rule, this requires time, money, search for compromises.

In order to reduce the decision costs associated with the unanimity rule, the majority rule is used. J. Buchanan and G. Tulloch proposed a model for determining the optimal majority (Fig. 14.3).

Rice. 14.3.Optimal majority according to J. Buchanan and G. Tulloch

Buchanan J., Tulloch G. Consent calculation. Logical foundations

constitutional democracy // Buchanan J. Works. – P. 99–105.

The costs incurred by the team when making a decision can be divided into internal (deviations in utility levels from those values that could be achieved with a unanimous decision) and external costs. In order for a decision to be made, the individual must spend some time and effort to develop a collective choice and achieve agreement in the group - these are external costs (curve FROM). A rational individual at the moment of a constitutional choice will try to make a decision that will allow him to minimize the amount of costs associated with its adoption. Optimal Majority (K/N) is determined by the number of voters that minimizes the total cost.

simple majority rule assumes that of the two options proposed for consideration, the one in favor of which more than half of those participating in the procedure will speak out will be chosen. It is optimal for a group in which the opportunity cost of time is of great importance.

Condorcet's rule according to which the voting options are compared in pairs. The option with the most votes is better than any other (by comparing each option with each other) wins.

Board rule allows for a single application of the procedure to make a choice between several different alternatives. At the same time, each agent ranks the states of society and assigns numbers (ranks) to different states in accordance with their preferences: 1 is assigned to the most preferred one; 2 - next, etc. According to the rule, the winner is the alternative with the smallest sum of ranks over all individuals.

The rule of choice "by tradition" assumes the presence of some given preferences, which are considered traditional. With any preferences of individuals, the choice will be made in accordance with traditional preferences.

In conditions of direct democracy, when decisions are made by a majority of votes, it is possible to choose in favor of an economically inefficient result; all decisions tend to be in the interests of the median voter.

Median voter model- a model that characterizes the tendency according to which decision-making within the framework of direct democracy is carried out in accordance with the interests of a person occupying a place in the middle of the scale of interests of a given society.

A rationally acting politician seeks to secure the support of the largest possible number of voters; however, it can be found by sticking to the central part of the political spectrum.

Let there be some set of alternatives located on the same scale (Fig. 14.4). These may be, for example, different amounts of total budget expenditures or the parameters of a particular social program.

Rice. 14.4.Scale of political alternatives

in letters (A, B, C, D, E, F, F) we denote the alternatives, each of which is most preferable for one of the voting individuals (or groups of voters of the same size). If out of three politicians one advocates an alternative BUT, second G, and the third D, then in elections held in several rounds, the first will be clearly uncompetitive, and the third will ultimately yield to the second.

The advantage of the third politician is that his position coincides with the point of view of the median voter, on both sides of which there is on the scale equal number alternatives supported by other voters. It should be noted that the position of the median voter is not necessarily located exactly in the center of the scale; it is important that he occupies a middle position among the voters. In this case, he is provided with the possibility of a coalition with at least half of the remaining voters, which means that the alternative approved by him will receive the majority of votes.

When comparing alternatives G and D everyone who is "to the left" G(these are supporters of the position BUT,B,AT), support G, and when compared G and BUT the coalition with the “median voter” will be joined by everyone who is “to the right” of him ( D, E and AND), and perhaps also B and AT. The latter already depends on the ratio of "distances" on a scale from these points to BUT and G. The defining role of the “median voter” is a real and very important trend in political life and the development of the public sector. It is especially noticeable in stable, relatively homogeneous societies. They are characterized, in particular, by successive electoral victories of two or three moderate parties, whose programs diverge approximately within the same range in which the preferences of the “median voter” can fluctuate.

The median voter model is also relevant for representative democracy, but in this case the situation becomes more complicated. A politician, in order to achieve his goal, very often has to make significant adjustments to his original program or abandon its original principles.

In a representative democracy, the voting process becomes more complicated, but it also has a number of advantages. Elected deputies specialize in making decisions on certain issues; Legislative assemblies organize and direct the activities of the executive power, monitor the implementation of decisions made.

However, public choice theory shows that one cannot fully rely on the results of voting, moreover, the very democratic procedure of voting in legislative bodies does not prevent the adoption of inefficient economic decisions.

The situation in which a stable collective choice is not feasible is described, in particular, by the well-known voting paradox. This is a contradiction that arises from the fact that majority voting does not provide for the identification of real public preferences.

Assume that there are three equal groups of voters, or parliamentary factions (I, II and III), who have to choose from three alternatives, one of which is, for example, a tax cut. (H), the other is an increase in defense spending (O), and the third is the expansion of the health protection program (Z). Table 14.1 presents two of the possible preference profiles. preference profile is a description of the order in which the participants in the choice rank the available alternatives.

Table 14.1

Preference profiles

| First option | Second option |

| I: N, O, Z | I: N, O, Z |

| II: O, N, Z | II: O, Z, N |

| III: N, Z, O | III: Z, N, O |

In the first variant, group I prefers tax cuts most of all, the strengthening of defense is less highly valued, and the development of health care is even lower; for Group II, defense comes first, tax cuts come second, and healthcare comes third; for group III, tax cuts are most important, followed by health care, and defense is the least attractive. In whatever order the alternatives are put to the vote H, O, W will receive support H. For example, if you first compare O and W, then by votes I and II, support is given to O, and then when comparing O and H victory will go H by votes I and III. The same result will be achieved if first matched O and H or H and W. Alternative H will be chosen, and if the decision is made in some other way (but with the preservation of the majority principle), for example, if the least popular alternative is cut off first, and then the remaining two are compared.

However, if the preference profile corresponds to the second option, then round robin, which is the content of the paradox. If the second option compares H and O, votes I and III give preference to H. At the next step, when comparing N and Z, support is received by W by votes II and III. However, if we compare W and O, then the advantage will go to the alternative rejected at the very beginning O, after which a new cycle of comparisons will lead to the same unstable results.

In this case, preferences are not transitive, in which the selection process can continue indefinitely without providing a stable outcome. If the procedure involves stopping, then two cases are possible: either the order in which the alternatives are compared is chosen at random, in which case the result of the choice is arbitrary, or the order of comparisons is controlled by one of the participants, in which case this participant is able to achieve the result that he prefers, those. the result is manipulated. In both cases, the procedure is difficult to recognize as rational. It is customary to call a choice rational, which is characterized by both completeness and transitivity.

The paradox of voting shows that the generally accepted approach to the implementation of the collective choice, based on the principle of the majority, does not provide rationality, i.e. the requirement of rationality is incompatible for him with the requirement of universality. The answer gives impossibility theorem, proved by K. Arrow. Arrow's theorem states that there is no social choice rule that simultaneously satisfies the following requirements (axioms):

unanimity;

the absence of a dictator;

· transitivity;

coverage (completeness and universality);

Independence from outside alternatives.

In other words, the impossibility theorem reveals that for any choice procedure, if it is collective (there is no “dictator”), there can be such preference profiles for which there is no stable, unmanipulable voting outcome.

From this point of view, collective choice is more vulnerable than individual choice. The absence of a collective decision that would not be arbitrary or manipulated is the more likely, the more significant the dissimilarity of individual positions and conflicts of interest, and the heterogeneity of issues contained in one program, the multiplicity of criteria used.

14.3. Special interest groups. Lobbying. Logrolling.

bureaucracy model. Seeking political rent

Politicians and civil servants cannot be equally familiar with all aspects of the problems they are solving. Moreover, they, like voters, are characterized by rational ignorance. So, if a member of parliament is elected predominantly by the votes of rural residents, is interested mainly in their support and deals primarily with agricultural issues, then, participating in voting, for example, on amendments to the copyright law, he is unlikely to study in detail the history of the issue, the advantages and disadvantages of possible solutions, etc.

Interest groups often concentrate their efforts on forming the position they need not so much of the voters themselves as of the authorities. This is achieved through lobbying. Lobbying- these are attempts to influence representatives of the authorities in order to make a political decision that is beneficial for a limited group of voters. Explicit abuses aside, the point of lobbying is to explain to the authorities the position of the group concerned and to present arguments in its defense.

If lobbying becomes widespread, it becomes a sphere of competition for groups that defend divergent, sometimes opposing interests. Each of the groups is forced to oppose its own arguments and methods of influence to the arguments and actions of rivals. In principle, multidirectional influences can be balanced. But differences in the activity and cohesion of special interest groups, and most importantly, in their resource capabilities, can give rise to noticeable shifts in the positions of authorities.

A great contribution to the analysis of special interest groups and the theory of lobbying was made by the permanent head of the Center for the Study of Collective Choice of the University of Maryland, Professor Mansoor Olson (1932–1998).

In legislative activities, politicians seek to increase their popularity by using a system logrolling("rolling the log"). This is the practice of mutual support for political decisions through the trading of votes. Each deputy chooses the most important issues for his voters and seeks to obtain the necessary support from other deputies. A deputy buys support on his own issues, giving his vote in return in defense of the projects and programs of his colleagues. Not all vote trading is a negative phenomenon, sometimes with the help of logrolling it is possible to achieve a more efficient distribution of economic resources. However, the opposite effect cannot be ruled out.

The classic form of logrolling is the "barrel of bacon" - a law that includes a set of small local projects that various groups of deputies are interested in adopting.

The interaction of voters and politicians, as well as the decisions of representative bodies, usually determine only general strategies for the development of the public sector. Its concretization and implementation are the tasks of the executive authorities. At the direct disposal of these bodies is the legal right of coercion, which distinguishes the state from other subjects of the market economy.

In the theory of public choice, the state apparatus and its employees are usually denoted by the term "bureaucracy". The bureaucracy does not produce economic benefits and extracts part of the income from sources not related to the sale of the results of its activities. In this case, those deliberately negative associations that are associated with this term in Russian are not necessarily implied. In particular, constant conscious deviations from the performance of duty are by no means assumed.

While entrepreneurs are guided by a profit margin that can be accurately measured, politicians have ultimately quantified criteria for success (electoral victory); the state apparatus is busy with the implementation of heterogeneous, often amenable to not quite unambiguous interpretation of the decisions of representative bodies. It is easier to fulfill this mission, the more resources are at the disposal of the bureaucracy. At the same time, there are usually no clear and universal criteria for evaluating performance.

The apparatus of executive bodies not only implements the adopted political decisions, but actually participates in the preparation of most of them. At the same time, the bureaucracy shows its interest in easing resource constraints and not defining tasks too rigidly. Employees of specialized state bodies have significant advantages in being informed on specific issues, which allows them to form the opinions of politicians. Often there are informal coalitions between specialized bodies and interest groups advocating the adoption of the same projects.

The bureaucracy is not interested in conflicts with active special interest groups. The position of civil servants, especially high-ranking ones, depends on the approval of politicians and the public. Those government agencies and officials who have managed to enlist the sympathy of active influential groups can count on their support even in the event of a clear failure.

Bureaucracy is most often characterized by the desire for stability. An entrepreneur is often ready to take risks and make fundamental changes, since, on the one hand, he manages his own resources, and on the other hand, if successful, the result will be his profit. It is more difficult for civil servants to undertake major innovations because they spend public funds and are constrained by regulations. If the innovation brings a huge return, the employee who proposed it is likely to receive only a relatively modest bonus or another position.

The greater the advantages of bureaucracy in terms of information and its real influence on political decision-making, the more likely, all other things being equal, the excessive expenditure of resources in the public sector and the conservation of non-optimal options for its development.

A certain interest in economy and innovation is created by competition between bodies that perform similar or interchangeable functions. Each of them, seeking to expand the scope of their competence and increase the degree of influence, can look for the most effective solutions.

Public choice theory considers several models of bureaucracy.

U. Niskanen for the first time approached the study of the activities of bureaucratic institutions from the standpoint of a cost-benefit analysis. The focus of his attention was on the questions: what is the volume of output? what are the costs of its production? How do inputs and outputs change with changing conditions? In relation to the firm, this meant the ratio of budget and output.

William Arthur Niskanen: From Practice to Theory of Bureaucracy

William Arthur Niskanen was born in 1933. He graduated from the University of Chicago in 1957 and worked as a staff economist for five years (1957–1962) at the RAND Corporation, the largest public welfare and safety research center. USA. In this “thinking tank”, quite large economists dealt with the problems of the military-industrial complex, among which Armen Alchiyan, George Danzig, William Sharp and others can be mentioned. Over the years, he not only noticeably succeeded in matters of military logistics, but also prepared a doctoral dissertation “ Demand alcoholic drinks”, which he defended at the University of Chicago.

Since 1962, U. Niskanen has been working at the US Department of Defense, where he directs special research in the Systems Analysis Department. In 1964, he was appointed director of the Department of Economic and Political Studies of the Institute for Defense Studies. It was at this time that his interest in public choice theory was born. In 1971, his monograph "Bureocracy and Representative Government" appeared. From September 1972 to July 1975, U. Niskanen was professor at the School of Public Policy at the University of California (Berkeley). From 1975 to 1980, he again becomes a bureaucrat, but this time in a private company, holding the post of director of economics for Ford. From 1981 to 1984, he was one of the economic advisers to the Reagan administration, which served as the basis for his book Reaganomics (1988).

However, the desire for political and economic research gradually began to prevail over the vocation of a political analyst. From 1985 to the present, William Niskanen has served as chairman of the board and staff economist at the Cato Institute in Washington. The Cato Institute is a non-governmental institution that analyzes the American economy from the standpoint of classical liberalism (libertarianism). It was during these years that his theory of bureaucracy became one of the main areas of research in the new political economy. Continuing the traditions of G. Tulloch and E. Downes, U. Niskanen creates an original model of a maximizing bureaucrat, which he significantly refined and developed in his works of the 1990s. His great contribution to the development of the new political economy was recognized by his election as President of the Public Choice Society (1998–2000).

The development of Niskanen's concept went through two phases; the original version was reflected in the 1971 book Bureaucracy and Representative Government; a more general model was formulated in 1975. Its essence was that a bureau is an organization that supplies a given amount of public goods for a monopoly buyer of its services. This buyer is usually a group of political officials. In turn, the bureau is also a monopoly. There is a situation of bilateral monopoly, a feature of which is the exchange of promised products for the budget allocated by the bureau. As with any bilateral monopoly, there is no single equilibrium. The conclusion from the model, which is by no means indisputable, was that, except in some special cases, the output from budget maximization was carried out efficiently by the bureaucracy.

Niskanen's model gave a broad impetus to the study of the behavior of bureaucracy. However, she left aside questions of the institutional environment in which the bureau operates. Therefore, the issues of further development of the theory of bureaucracy are closely related to the development of the problems of constitutional economics.

Unlike U. Niskanen, G. Tulloch (1974) approaches the analysis of bureaucracy as a dynamic process. He is interested in the growth factors of the bureau. It uses an exponential growth function for this. The maximization of the budget by a rational individual is expressed in an increase in the number of employed bureaus.

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru

PUBLIC CHOICE THEORY

Introduction

Chapter 1 Public Choice Theory

1.1 History of the development of public choice theory

1.2 Genesis of public choice theory

Chapter 2

2.1 Background of public choice theory

2.2 Logrolling and political rent seeking

Chapter 3

3.1 Using public choice theory to predict the behavior of voters and politicians

3.2 Using Public Choice Theory to Predict Bureaucracy Behavior

Conclusion

List of used literature

INTRODUCTION

Public choice theory is a branch of economic science that studies the patterns of choice of government activities in the field of economics and how this choice is made under the pressure of a democratic system.

This theory is based on the basic idea that a person in any area of his activity seeks to maximize the result in his own interests. As an independent direction of economic science, it was formed in the 1950s and 60s. However, in a modern interpretation, it originates from the work of J. Buchanan "The Limits of Freedom" (1975). public choice voter politician

Public choice theory is sometimes referred to as the "new political economy" because it deals with the study of the political mechanism of macroeconomic decision-making. According to Buchanan, this theory is based on three main premises: methodological individualism, the concept of "economic man" and the analysis of politics as a process of exchange.

Representatives of the theory of public choice consider the political market by analogy with the commodity market, where the state is also a market in which voters and politicians exchange votes and election promises in order to gain access to the distribution of resources and places on the hierarchical ladder. At the same time, the activities of state representatives are often far from ideal.

According to this theory, the failures of the state include: a) the limited information necessary for decision-making (the presence of an active lobby and a powerful bureaucratic apparatus leads to a significant distortion of the available information); b) imperfection of the political process (manipulation of votes, bureaucracy, search for political rent); c) limited control over the bureaucracy (the larger the state apparatus, the more difficult it is to fight the bureaucracy); d) the inability of the state and persons representing it to foresee and effectively control the immediate and long-term consequences of government decisions.

Every person has faced in his life the need to make a choice. The future of a person depends on it, any wrong step can destroy a career, family life, the fate of other people. All the more important is the right choice in solving state issues.

The study of the mechanisms of public choice is extremely important for politicians in order to find support from the people, managers, in order to better understand how public demand is formed, entrepreneurs, since the external environment has a direct impact on any firm.

Based on this and taking into account the foregoing, we can conclude that the topic of public choice is very relevant.

Among the foreign scientists involved in the study of this problem, one can note J. Buchanan, Muller Denis, D. Tulloch and others. Among domestic scientists, Nureyev R. M. can be noted.

The main purpose of this work is to consider the theory of public choice. The goal set in the work determined the objectives of the study, namely:

1. Analyze the genesis and main provisions of the theory of public choice.

2. Consider the possibilities of practical application of the provisions of the theory of public choice.

CHAPTER 1. PUBLIC CHOICE THEORY

1.1 History of the development of public choice theory

One of the founders of public choice theory is the American economist James McGill Buchanan.

An important role in the formation of the theory of public choice was played by the works on the political philosophy of T. Hobbes, B. Spinoza, as well as the political science studies of J. Madison and A. de Tocqueville. As an independent direction of economic science, it was formed only in the 50-60s of the XX century.

The discussions of the 1930s and 1940s gave an immediate impetus to the theory of public choice. on problems of market socialism and welfare economics (A. Bergson, P. Samuelson).

A wide response in the 1960s was caused by K. Arrow's book "Social Choice and Individual Values" (1st ed. 1951, 2nd ed. 1963), which drew an analogy between the state and the individual. In contrast to this approach, J. Buchanan and G. Tulloch in the book "The Calculation of Consent" (1962) drew an analogy between the state and the market. The relationship of citizens with the state was considered in accordance with the principle of "quid pro quo" (quid pro quo).

Trade in the political market develops primarily in connection with externalities and public goods. In the 1960s, Buchanan published a number of papers on these issues. First of all, it should be noted the book “Fiscal Theory and Political Economy” (1960), the articles “Externalities” (1962, written jointly with W. Stubblebin), “The Economic Theory of Clubs” (1965) and the book “Public Finance in the Democratic Process” ( 1966). It was these ideas, further developed in Buchanan's "The Limits of Freedom" (1975), that contributed to the spread of public choice theory. After the publication of this work, the popularity of Buchanan's ideas among academic economists increased dramatically.

Buchanan and Richard Wagner, in Democracy in Shortfall (1977), argued for the constitutional requirement for a balanced budget. In The Power of Taxation (1980), written by Buchanan with Geoffrey Brennan, this theme is developed further. In particular, it justifies constitutional restrictions on the government's rights in the field of taxation. Thus, Buchanan approaches the idea of a balanced state budget from two sides - from the side of expenditures and from the side of income.

In 1985, another work by Buchanan was published, written jointly with J. Brennan, "The Foundations of the Rules." It substantiates the importance of norms and rules in all spheres of society. The authors of the book compare the rules of the market and political orders. They deepen the understanding of the contractual (contractual) foundations of society, comparing the political "playing by the rules" with "playing without any rules" and analyzing their consequences. This book raises the question of the possibility of a constitutional revolution in a democratic society, which should lead to the formation of a constitutional economy - an economy that can stop the unrestrained growth of the state apparatus, put it under the control of civil society.

Given all of the above, we can conclude that public choice theory is one of the branches of economics that studies the various ways and methods by which people use government institutions for their own interests.

1. 2 Genesis of the theorypublic choice

Public choice theory is one of the most striking areas of economic imperialism, associated with the application of the methodology of neoclassical economic theory to study political processes and phenomena.

The theory of public choice is sometimes called the "new political economy", as it studies the political mechanism of formation of macroeconomic decisions. Criticizing the Keynesians, the representatives of this theory questioned the effectiveness of government intervention in the economy. Consistently using the principles of classical liberalism and the methods of microeconomic analysis, they actively invaded the area traditionally considered the field of activity of political scientists, lawyers, sociologists (such intervention was called "economic imperialism").

Criticizing state regulation, representatives of the theory of public choice made the object of analysis not the impact of monetary and financial measures on the economy, but the process of making government decisions.

Originating in the 1960s as a branch of economics dealing with taxation and government spending, public choice theory has greatly expanded its scope of analysis in the following decades and can now be considered as a discipline that rightly claims to be the economics of politics.

The ideas underlying the theory of public choice were first formulated at the end of the 19th century by representatives of the Italian school of public finance: M. Pantaleoni, U. Mazzola, A. De Viti de Marco and others.

This approach was further developed in the works of representatives of the Swedish school in economics- K. Wicksell and E. Lindahl, who paid primary attention to political processes that ensure the definition of state budgetary policy.

The developed approaches remained practically unknown to other researchers for a long time. At the same time, in the 1940-50s, ideas about the rational nature of the behavior of individuals in the political sphere began to actively penetrate into scientific discussions, thanks to the works of J. Schumpeter, C. Arrow, D. Black, E. Downes published during this period.

The combination of these two directions became the basis for the development of a set of ideas now known as public choice theory. Representatives of the so-called Virginia School of Economics played a key role in this. The recognized leader of this school is J. Buchanan, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1986.

Thanks to the numerous works of J. Buchanan, as well as other specialists in the field of public choice theory, such as J. Brennan, W. Niskanen, M. Olson, G. Tulloch, R. Tollison and others, since the early 1960s, there has been Significant progress has been made in developing both the basic ideas of public choice theory and child theories based on these ideas.

In conditions of limited resources, each of us is faced with the choice of one of the available alternatives. Methods for analyzing market behavior are universal. They can be successfully applied to any of the areas where a person must make a choice.

The basic premise of public choice theory is that people act in the political sphere in pursuit of their own self-interest. Rational politicians support, first of all, those programs that contribute to the growth of their prestige and increase the chances of winning the next election. Thus, public choice theory attempts to consistently implement the principles of individualism, extending them to all types of activity, including public service.

The second premise of public choice theory is the concept of the economic man. A person in a market economy identifies his ideas with the product. He seeks to make decisions that maximize the value of the utility function.

His behavior is rational. The rationality of the individual has a universal meaning in this theory. This means that everyone, from voters to the president, is guided in their activities primarily by the economic principle, i.e. compare marginal benefits and marginal costs: MB > MC, where MB is the marginal benefit; MC - marginal cost.

The third premise, the interpretation of politics as a process of exchange, goes back to the dissertation of the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell "Studies in the Theory of Finance" (1896). He saw the main difference between economic and political markets in terms of the manifestation of people's interests. This idea formed the basis of the work of the American economist J. Buchanan.

Proponents of the theory of public choice consider the political market by analogy with the commodity. The state is an arena of people's competition for influence on decision-making, for access to the distribution of resources, for a place in the hierarchical ladder. However, the state is a special kind of market. Its participants have unusual property rights: voters can choose representatives to the highest bodies of the state, deputies - to pass laws, officials - to monitor their implementation. Voters and politicians are treated as individuals exchanging votes and campaign promises.

A basic tenet of public choice theory is that people act in the same way in their private roles as they do in any public role. In analyzing people's personal choices, economists have long concluded that people act in the rational pursuit of personal gain. As consumers, they maximize utility; as entrepreneurs they maximize profits, and so on.

A decision made by or on behalf of a group is sometimes called a public choice. The study of a market economy has largely focused on the choices made by individuals, but in all economies many decisions regarding the allocation of resources are made by governments or other groups.

Economists are interested in the ways in which such collective decisions are made and the resource allocations to which they lead. Economists are particularly interested in the Pareto optimality of collective decisions and the degree to which such decisions reflect the personal preferences of individuals.

Impossibility theorem K.J. Arrow points out that there are serious difficulties in forming collective choices based on individual values.

Summarizing all the above, we can draw the following conclusions:

1) representatives of the theory of public choice made the object of analysis not the impact of monetary and financial measures on the economy, but the process of making government decisions;

2) in conditions of limited resources, each of us faces the choice of one of the available alternatives.

3) methods of market behavior analysis are universal and can be successfully applied to any of the areas where a person has to make a choice.

4) Public choice theorists assume that the actions and choices of people in public office are also driven by considerations of personal gain.

CHAPTER 2. MAIN PROVISIONS OF THE THEORY OF PUBLIC CHOICE

2.1 Background of public choice theory

Public Choice Theory- one of the modern neo-institutional economic theories, formed in the 50-60s. 20th century Its founder is the American scientist-economist J. Buchanan, who received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986 for research in the field of public choice theory.

Public choice theory is sometimes called the new political economy because it studies the political mechanism of macroeconomic decision making.

Criticizing the Keynesians, representatives public choice theories have questioned the effectiveness of government intervention in the economy. Consistently using the principles of classical liberalism and the methods of microeconomic analysis, they actively invaded the area traditionally considered the field of activity of political scientists, lawyers and sociologists. This intervention was called economic imperialism.

Proponents of the theory of public choice consider the political market by analogy with the commodity. The state is an arena of people's competition for influence on decision-making, for access to the distribution of resources, for a place on the hierarchical ladder. However, the state is a special kind of market. Its participants have unusual property rights: voters can choose representatives to the highest bodies of the state, deputies - to pass laws, officials - to monitor their implementation. Voters and politicians are treated as individuals exchanging votes and campaign promises.

The object of analysis of this theory is the public choice in conditions of both direct and representative democracy. Therefore, the main areas of its analysis are the electoral process, the activities of deputies, the economics of the bureaucracy and the policy of state regulation of the economy. By analogy with the perfectly competitive market, public choice theorists begin their analysis with direct democracy, moving on to representative democracy as the limiting factor.

Direct democracy is a political system in which every citizen has the right to personally express their point of view and vote on any specific issue.

Within the framework of direct democracy, there is a model of the so-called median voter, according to which decision-making is carried out in accordance with the interests of the centrist voter (a person who occupies a place in the middle of the scale of interests of a given society). At the same time, resolving issues in favor of the centrist voter has its pluses and minuses. On the one hand, it keeps the community from making unilateral decisions, from extremes, on the other hand, it does not always guarantee the adoption optimal solution, since even in conditions of direct democracy, when decisions are made by a majority of votes, it is possible to choose in favor of an economically inefficient result (for example, underproduction or overproduction of public goods). The fact is that such a voting mechanism does not allow taking into account the totality of the benefits of an individual.

The median voter model is also relevant for representative democracy, but here the selection procedure becomes more complicated. A presidential candidate, in order to achieve his goal, must appeal to the centrist voter at least twice: first within the party (for his nomination from the party), and then to the median voter among the entire population. At the same time, in order to win the sympathy of the majority, one has to make significant adjustments to one's original program, and often even abandon its fundamental principles.

Unlike private, public choice is carried out at certain intervals, limited by the circle of applicants, each of which offers its own package of programs. The latter means that the voter is deprived of the opportunity to elect several deputies: one - to solve employment problems, another - to fight inflation, the third - on problems foreign policy etc. He is forced to elect one deputy, whose position does not completely coincide with his preferences.

Representative democracy has a number of undeniable advantages. In particular, it successfully uses the benefits of the social division of labor. Elected deputies specialize in making decisions on certain issues. Legislative assemblies organize and direct the activities of the executive power, monitor the implementation of decisions made.

At the same time, in a representative democracy, it is possible to make decisions that do not correspond to the interests and aspirations of the majority of the population, which are very far from the model of the median voter. Prerequisites are being created for making decisions in the interests of a narrow group of people. Ways of influencing representatives of power in order to make a political decision beneficial to a limited group of voters are called lobbying.