Functions of introductory and plug-in constructions, their structural types, functional-semantic classification. Summary: Syntactic stylistics Stylistic use of introductory and insert structures

Against the background of various syntactic means of appeal, they stand out for their expressive coloring and functional and stylistic fixation. Of greatest interest is the use of addresses by writers, which also reflect the intonations of tenderness and participation characteristic of colloquial speech: I remember, beloved, I remember; Ah, Tolya, Tolya!; Are you still alive, my old lady? (Ec.), and familiarity or even rudeness: Here we are. Hello, old (N.); Oh, you red-headed fool, what have you done (from the magazine), and mockery, mockery: Where, clever, are you wandering, head [to the Donkey]? (Cr.)

At the same time, the emotional sound of appeals in a poetic text often reaches high pathos: Pets of a windy Fate, tyrants of the world! tremble! And you, take heart and listen, rise up, fallen slaves! (P.), murderous sarcasm: Farewell, unwashed Russia, a country of slaves, a country of masters, and you, blue uniforms, and you, a people devoted to them (L.), bright pictorial power: You are my fallen maple, icy maple (Es. ); Farewell, free element! (P.)

To create the emotionality of speech, writers can use words with bright expressive coloring as appeals: an autocratic villain; haughty descendants, figurative paraphrases: O Volga, my cradle, did anyone love you like I do? (N) In addition, epithets are often used when addressing, and they themselves are often tropes - metaphors, metonyms: Throw me, fire tower, to scare people (Bub.), Come here, beard! Their expression is emphasized by particles: Hey, coachman!; Come on, my friend; tautological combinations, pleonasms: Wind, wind, you are mighty (P.); Wind-wind!; Sea-Okian, finally, a special intonation - all this enhances the expressive power of this syntactic device in artistic speech.

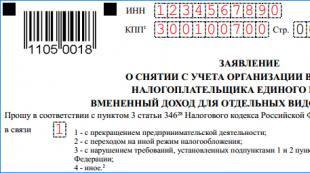

However, appeals are sometimes needed in texts that are devoid of imagery and do not allow the use of expressive elements, in business correspondence, official documents addressed to certain individuals. But here the function of appeals is different: they play an informative role (indicate to whom the document is addressed), and also organize the text, acting as a kind of “beginning”.

In official business speech, stable combinations have been developed that serve as appeals in certain situations: dear sir, citizen, ladies and gentlemen, etc. Some of the previously used addresses are outdated: dear, venerable. The choice of the form of address in an official setting is important, since speech etiquette is an integral part of the culture of behavior, and in special situations it also acquires a socio-political connotation.

The use of introductory words and phrases in speech requires a stylistic comment, since they, expressing certain evaluative meanings, give an expressive coloring to the statement and are often assigned to the functional style. Stylistically unjustified use of introductory words and phrases damages the culture of speech. Appeal to them may be associated with the aesthetic attitude of writers and poets. All this is of undoubted stylistic interest.

If we start from the traditional classification of the main meanings of the introductory components, it is easy to identify their types that are attached to one or another functional style. So, introductory words and phrases expressing reliability, confidence, assumption: undoubtedly, of course, probably, possibly - gravitate towards book styles.

Introductory words and phrases used to attract the attention of the interlocutor, as a rule, function in a colloquial style, their element is oral speech. But the writers, skillfully inserting them into the dialogues of the characters, imitate a casual conversation: - Our friend Popov is a nice fellow, - Smirnov said with tears in his eyes, - I love him, I deeply appreciate his talent, I am in love with him, but ... you know? - this money will ruin him (Ch.). Such introductory units include: listen, agree, imagine, imagine, do you believe, remember, understand, do me a favor and under. Abuse of them sharply reduces the culture of speech.

A significant group consists of words and phrases expressing an emotional assessment of the message: fortunately, to surprise, unfortunately, to shame, to joy, to misfortune, an amazing thing, a sinful thing, there is nothing to hide and under. Expressing joy, pleasure, chagrin, surprise, they give speech an expressive coloring and therefore cannot be used in strict texts of book speech, but are often used in live communication between people and in works of art.

Introductory sentences expressing roughly the same shades of meaning as introductory words, in contrast to them, are stylistically more independent. This is due to the fact that they are more diverse in terms of lexical composition and volume. But the main sphere of their use is oral speech (which the introductory sentences enrich intonation, giving it special expressiveness), as well as artistic, but not book styles, in which, as a rule, shorter introductory units are preferred.

Introductory sentences can be quite common: While our hero, as they wrote in novels in the leisurely good old days, goes to the illuminated windows, we will have time to tell what a village party is (Sol.); but more often they are quite laconic: you know, you should notice, if I'm not mistaken, etc.

Insert words, phrases and sentences are additional, incidental remarks in the text.

Here are a few examples of the stylistically perfect inclusion of insert structures in a poetic text: Believe me (conscience is a guarantee), marriage will be torment for us (P.); When I begin to die, and, believe me, you will not have long to wait - you were led to transfer me to our garden (L.); And every evening, at the appointed hour (or is it just a dream of mine?), the girlish camp, seized with silks, moves in the foggy window (Bl.).

The use of introductory words and phrases in speech requires a stylistic comment, since they, expressing certain evaluative meanings, give an expressive coloring to the statement and are often assigned to the functional style. Stylistically unjustified use of introductory words and phrases damages the culture of speech. Appeal to them may be associated with the aesthetic attitude of writers and poets. All this is of undoubted stylistic interest.

If we start from the traditional classification of the main meanings of the introductory components, it is easy to identify their types that are attached to one or another functional style. So, introductory words and phrases expressing reliability, confidence, assumption: certainly, of course, probably, probably, - gravitate toward book styles.

Introductory words and phrases used to attract the attention of the interlocutor, as a rule, function in a colloquial style, their element is oral speech. But the writers, skillfully inserting them into the dialogues of the characters, imitate a casual conversation: - Our friend Popov is a nice fellow,” Smirnov said with tears in his eyes, “I love him, deeply appreciate his talent, I’m in love with him, but… you know? - this money will ruin him(Ch.). These input units include: listen, agree, imagine, imagine, do you believe, remember, understand, do me a favor and under. Abuse of them sharply reduces the culture of speech.

A significant group consists of words and phrases expressing an emotional assessment of the message: fortunately, to surprise, unfortunately, to shame, to joy, to misfortune, an amazing thing, a sinful thing, there is nothing to hide a sin and under. Expressing joy, pleasure, chagrin, surprise, they give speech an expressive coloring and therefore cannot be used in strict texts of book speech, but are often used in live communication between people and in works of art.

Introductory sentences expressing roughly the same shades of meaning as introductory words, in contrast to them, are stylistically more independent. This is due to the fact that they are more diverse in terms of lexical composition and volume. But the main sphere of their use is oral speech (which introductory sentences are enriched intonation, giving it special expressiveness), as well as artistic, but not bookish styles, in which, as a rule, preference is given to shorter introductory units.

Introductory sentences can be quite common: While our hero, as they wrote in novels in the leisurely good old days, goes to the illuminated windows, we will have time to tell what a village party is.(Sol.); but more often they are quite concise: you know, you should notice if I'm not mistaken etc.

Plug-in words, phrases and sentences are additional, incidental remarks in the text.

Here are some examples of the stylistically perfect inclusion of insert structures in a poetic text: Believe (conscience is a surety), marriage will be torture for us(P.); When I start to die, and, believe me, you won't have long to wait - you will take me to our garden(L.); And every evening, at the appointed hour (Or is it just me dreaming?), girlish figure, seized by silks, moves in a foggy window(Bl.).

38.Stylistic use various types complex sentence

The use of complex sentences is a hallmark of book styles. In colloquial speech, especially in its oral form, we use mostly simple sentences, and very often incomplete ones (the absence of certain members is made up for by facial expressions and gestures); less commonly used are complex (mainly non-union). This is due to extralinguistic factors: the content of statements usually does not require complex syntactic constructions that would reflect the logical and grammatical connections between predicative units combined into complex syntactic constructions; the absence of unions is compensated by intonation, which acquires decisive importance in oral speech for expressing various shades of semantic and syntactic relations.

Without dwelling in detail on the syntax of the oral form of colloquial speech, we note that when it is reflected in writing in literary texts, and above all in dramaturgy, non-union complex sentences are most widely used. For example, in the drama of A.P. Chekhov "The Cherry Orchard" I don't think we can do anything. He has a lot to do, is he not up to me? and pays no attention. God be with him at all, it's hard for me to see him. Everyone talks about our wedding, everyone congratulates, but in reality there is nothing, everything is like a dream.

In stage speech, the richness of intonation makes up for the absence of unions. Let's do a simple experiment. Let's try to connect the predicative units combined into complex non-union sentences in the quoted passage using conjunctions: I don't think we will get anything. He has a lot to do, so he is not up to me, and therefore does not pay attention. Everyone is talking about our wedding, so everyone is congratulating us, even though there is nothing really.

Such constructions seem unnatural in an atmosphere of relaxed conversation; non-union proposals convey its character more vividly. Compounds are also close to them (in the quoted passage, only one is used - with the adversative union a).

From this, of course, it does not follow that complex sentences are not presented in artistic speech, reflecting colloquial speech. They exist, but their repertoire is not rich, besides, these are often two-part sentences of a “lightweight” composition: The main action, Kharlampy Spiridonych, is not to forget your work; Ah, what are you? I already told you that I'm not in my voice today(Ch.).

In book functional styles, complex syntactic constructions with various types of coordinating and subordinating connections are widely used. "Pure" compound sentences in book styles are relatively rare, since they do not express the whole variety of causal, conditional, temporal and other relationships that arise between predicative units in scientific, journalistic, official business texts. Referring to compound sentences is justified when describing any facts, observations, stating the results of research:

A friendly conversation is not regulated by anything, and the interlocutors can talk on any topic? Another thing is when a patient talks with a doctor. The patient is waiting for help from the doctor, and the doctor is ready to provide it. At the same time, the patient and the doctor may know absolutely nothing about each other before the meeting, but they don’t need this for communication?

(Popular science article)

Much richer and more versatile in their stylistic and semantic features are complex sentences that occupy a worthy place in any of the book styles:

The fact that a scientific achievement can be turned not only to the benefit of society, but also to its detriment, people have known for a long time, but right now it has become especially clear that science can not only give people good, but also make them deeply unhappy, so never Previously, a scientist did not have such a moral responsibility to people for the biological, material and moral consequences of his searches, as he does today.

(From newspapers)

Complex sentences are, as it were, “adapted” to express complex semantic and grammatical relationships that are especially characteristic of the language of science: they allow not only to accurately formulate a particular thesis, but also to support it with the necessary argumentation, to give scientific justification.

The accuracy and persuasiveness of the structures of complex sentences in this case largely depends on the correct use of the means of communication of predicative parts in complex sentences (unions, allied and correlative words).

Stereotypes, which are often taken by people for knowledge, actually contain only an incomplete and one-sided description of some fact of reality. ... If stereotypes are measured by the criteria of scientific truth and strict logic, then they will have to be recognized as extremely imperfect means of thinking. Nevertheless, stereotypes exist and are widely used by people, although they do not realize it.

In this text, unions not only connect parts of complex sentences, but also establish logical connections between individual sentences as part of a complex syntactic whole: union and yet indicates the opposition of the last sentence of the previous part of the statement.

Among the subordinating conjunctions there are common ones, the use of which is possible in any style: what, to, because, how, if, but there are also purely bookish ones: due to the fact that, due to the fact that, due to the fact that, due to the fact that, due to the fact that, as soon as, and colloquial: once(in meaning if) Once said - do it; if that(in meaning how) People's rumor that the sea wave. A number of unions have an archaic or colloquial coloration: if, if, so that, ponezhe. Stylistically motivated and grammatically accurate use of conjunctions makes speech clear and convincing.

Let us dwell in more detail on the stylistic evaluation of complex sentences. In their composition, the most common are sentences with definitive and explanatory clauses (33.6% and 21.8% in comparison with all others). You can verify this by opening any newspaper and immediately discovering many such structures:

Glasnost, of course, should not be an end in itself. Glasnost should not turn into loudness of people who have nothing to say. We are not for the publicity of talkative nonsense, but for the publicity of thoughts that can be turned into the energy of action.

There are two complex sentences here, both with a clause. Another example from the newspaper:

Do you understand the lyrical delight that gripped the hero? It is only a pity that the author does not allow him to see any significant problems of the modern village, to think, for example, why, when meeting with the chairman, people have “polite and chilly impatience” on their faces.

In a complex sentence, there are two subordinate explanatory parts.

Such a quantitative and qualitative picture reflects the general regularity of book styles, which is due to extralinguistic factors. At the same time, one can also point out special features of styles that are expressed in the selectivity of certain types of complex sentences. Thus, the scientific style is characterized by the predominance of causal and conditional clauses (together they make up 22%) and the minimum number of temporal (2.2%), as well as clauses of place (0.4%).

In the official business style, in second place in terms of frequency after attributive clauses, there are conditional clauses. AT various types texts, the ratio of types of complex sentences, of course, changes, but the strong predominance of conditional clauses in genres of a legal nature and a rather significant percentage in others determines the overall quantitative and qualitative picture of this functional style.

In book styles, the preference for certain syntactic constructions is quite justified, and the editor, like the author, cannot but reckon with this. The same syntactic constructions in different texts have various purpose. So, complex subordinate clauses with a conditional clause in publicistic speech much more often than in fiction receive a comparative meaning, approaching complex sentences in terms of the nature of the connection. If in the recent past the shelves in grocery stores were empty, now they surprise with the abundance and variety of products.(cf.: in past years were empty... and now...).

Comparative constructions with double conjunction if...then... are often used in critical articles and scientific papers: In their youth, if some were fond of Baudelaire, d'Annunzio, Oscar Wilde and already dreamed of new stage forms, others were busy with the plans of folk theaters(from the magazine); compare: some were addicted ... while others were busy with plans... Such a transformation of the semantic-stylistic function of these constructions fundamentally distinguishes journalistic and scientific texts from official business.

In the scientific style, temporary clauses are often complicated by an additional conditional meaning: A scientific hypothesis justifies itself when it is optimal., compare: in case she... The combination of conditional and temporal meanings in a number of cases leads to greater abstraction and generalization of the content expressed by them, which corresponds to the generalized abstract nature of scientific speech.

In artistic speech, where complex sentences with subordinate clauses of time are found four times more often than in scientific speech, the "purely temporary" meanings of these clauses are widely used; moreover, with the help of various conjunctions and the correlation of temporal forms of verbs-predicates, all kinds of shades of temporal relations are transmitted: duration, repetition, unexpectedness of actions, a gap in time between events, etc. This creates great expressive possibilities of artistic speech: A little light breeze will ripple the water, you will stagger, begin to weaken(Cr.); And as soon as the sky lit up, everything suddenly stirred noisily, flashed behind the formation(L.); I only smile when I hear the storm(N.); He has gone noticeably gray since we broke up with him.(T.); As she was leaving the drawing-room, a bell was heard in the hall.(L. T.); We walked until the reflections of the stars began to fade in the windows of the cottages.(Ch.).

Compound sentences with comparative clauses are used differently in book styles and artistic speech. In the scientific style, their role is to identify logical connections between compared facts, patterns: The possibility of formation of reflexes based on unconditional reflex changes in the electrical activity of the brain, just as it has been shown for exteroceptive signals, is another proof of the commonality of the mechanisms for the formation of exteroceptive and interoceptive temporary connections..

In artistic speech, the comparative clauses of complex sentences usually become tropes, performing not only a logical-syntactic, but also an expressive function: The air only occasionally trembled, as water trembles indignant at the fall of a branch; Small leaves are brightly and amicably green, as if someone washed them and put varnish on them.(T.).

Thus, if in book functional styles the choice of one or another type of complex sentence is associated, as a rule, with the logical side of the text, then in expressive speech its aesthetic side also becomes important: when choosing one or another type of complex sentence, its expressive possibilities are taken into account .

Stylistic evaluation of a complex sentence in different styles related to the problem of the sentence length criterion. An overly polynomial sentence can turn out to be heavy, cumbersome, and the ego will make it difficult to perceive the text, making it stylistically inferior. However, it would be a profound mistake to believe that short, “light” phrases are preferable in artistic speech.

M. Gorky wrote to one of the novice authors: “It is necessary to unlearn a short phrase, it is appropriate only at moments of the most intense action, a quick change of gestures, moods.” Speech is widespread, "smooth" gives "the reader a clear idea of what is happening, of the gradualness and inevitability of the depicted process" . In Gorky's own prose, one can find many examples of the skillful construction of complex syntactic constructions, in which an exhaustive description of the pictures of the surrounding life and the state of the characters is given.

He seethed and trembled at the insult inflicted on him by this young calf, whom he had despised while talking to him, and now he immediately hated him because he had such clear blue eyes, a healthy tanned face, short strong arms, because he has a village somewhere, a house in it, for the fact that a wealthy peasant invites him as a son-in-law - for all his life, past and future, and most of all for the fact that he, this child, in comparison with him, Chelkash, dares love freedom, which knows no price and which he does not need.

At the same time, it is interesting to note that the writer deliberately simplified the syntax of the novel "Mother", assuming that it would be read in circles of revolutionary workers, and long sentences and polynomial complex constructions are inconvenient for oral perception.

The master of the short phrase was A.P. Chekhov, whose style is distinguished by brilliant brevity. Giving instructions and advice to contemporary writers, Chekhov liked to focus on one of his fundamental principles: “Brevity is the sister of talent,” and recommended, if possible, to simplify complex syntactic constructions. So, editing the story of V.G. Korolenko "The forest is noisy", A.P. Chekhov excluded a number of subordinate clauses when abbreviating the text:

Grandfather's mustache dangles almost to the waist, his eyes look dull (as if grandfather is remembering something and cannot remember); Grandfather bowed his head and sat in silence for a minute (then, when he looked at me, his eyes flashed like a spark of awakened memory through the dull shell that covered them). Maxim and Zakhar will soon come from the forest, look at both of them: I don’t tell them anything, but only those who knew Roman and Opanas can immediately see who looks like whom (although they are already not sons to those people, but grandchildren?) Here are the things.

Of course, editing-abbreviation is not reduced to a thoughtless "struggle" with the use of complex sentences, it is due to many reasons of an aesthetic nature and is associated with the general tasks of working on a text. However, the rejection of subordinate parts, if they do not have an important informative and aesthetic function, could also be dictated by considerations of the choice of syntactic options - a simple or complex sentence.

At the same time, it would be absurd to say that Chekhov himself avoided complex structures. In his stories, you can learn many examples of their skillful use. The writer showed great skill, combining several predicative parts into one complex sentence without sacrificing either clarity or ease of construction:

And at pedagogical councils, he simply oppressed us with his caution, suspiciousness, and his purely case-based considerations about the fact that here in the men's and women's gymnasiums, young people are behaving badly, making a lot of noise in the classes - oh, no matter how it got to the authorities, oh no matter what happened, and that if Petrov were excluded from the second class, and Egorov from the fourth, it would be very good.

The master of stylistic use of complex syntactic constructions was L.N. Tolstoy. Simple, and especially short sentences, are rare in his work. Compound sentences are usually found in Tolstoy when depicting specific pictures (for example, in descriptions of nature):

The next morning, the bright sun that rose quickly ate the thin ice that covered the waters, and all the warm air trembled from the vapors of the obsolete earth that filled it. The young grass, old and emerging with needles, turned green, the buds of viburnum, currant and sticky spirit birch puffed out, and on the vine sprinkled with golden color, an exposed bee buzzed.

The writer's appeal to the life of society suggested to him a complicated syntax. Recall the beginning of the novel "Resurrection":

No matter how hard people tried, having gathered in one small place several hundred thousand, to disfigure the land on which they huddled, no matter how they stoned the earth so that nothing would grow on it, no matter how they cleaned off any breaking grass, no matter how they smoked coal and oil, no matter how they pruned the trees and drove out all the animals and birds, - spring was spring even in the city. The sun warmed, the grass, reviving, grew and turned green wherever they scraped it off, not only on the lawns of the boulevards, but also between the slabs of stones, and birches, poplars, bird cherry blossomed their sticky and odorous leaves, lindens puffed out bursting buds; jackdaws, sparrows and doves were already happily preparing their nests in the spring, and flies were buzzing along the walls, warmed by the sun. Plants, and birds, and insects, and children were cheerful. But people - big, adult people - did not stop deceiving and torturing themselves and each other. People believed that sacred and important is not this spring morning, not this beauty of the world of God, given for the benefit of all beings, - beauty that disposes to peace, harmony and love, but sacred and important is what they themselves invented in order to rule over each other. friend.

On the one hand, complicated constructions, on the other hand, simple, “transparent” ones, emphasize the contrasting juxtaposition of the tragedy of human relations and harmony in nature.

It is interesting to touch upon the problem of A.P. Chekhov of L. Tolstov's syntax. Chekhov found an aesthetic justification for the famous novelist's commitment to complicated syntax. S. Shchukin recalled Chekhov's remark: “Did you pay attention to Tolstoy's language? Enormous periods, proposals piled one on top of the other. Do not think that this is an accident, that this is a disadvantage. This is art, and it is given after labor. These periods give the impression of strength. In Chekhov’s unfinished work “Letter”, the same positive assessment of Tolstoy’s periods is expressed: “... what a fountain gushes from under these “who”, what a flexible, slender, deep thought hides under them, what a screaming truth!” .

The artistic speech of L. Tolstoy reflects his complex, in-depth analysis of the depicted life. The writer seeks to show the reader not the result of his observations (which could be easily presented in the form of simple, short sentences), but the search for truth itself.

Here is how the flow of thoughts and the change of feelings of Pierre Bezukhov are described:

“It would be nice to go to Kuragin,” he thought. But at once he remembered his word of honor given to Prince Andrei not to visit Kuragin.

But immediately, as happens with people who are called spineless, he so passionately wanted to once again experience this dissolute life so familiar to him that he decided to go. And immediately the thought occurred to him that this word meant nothing, because even before Prince Andrei, he also gave Prince Anatole the word to be with him; finally, he thought that all these words of honor were such conditional things, having no definite meaning, especially if you consider that perhaps tomorrow either he will die, or something so unusual will happen to him that there will be no more neither honest nor dishonest ... He went to Kuragin.

Analyzing this passage, we could transform it into one short sentence: Despite the word given to Prince Andrei, Pierre went to Kuragin. But it is important for the writer to show the hero's path to this decision, the struggle in his soul, hence the sentences of a complicated type. N.G. Chernyshevsky emphasized this ability of Tolstoy to reflect the “dialectic of the soul” of his characters: in their spiritual world, “some feelings and thoughts develop from others; it is interesting for him to observe how a feeling that directly arises from a given position or impression, subject to the influence of memories and the power of combination represented by the imagination, passes into other feelings, returns again to the same starting point, and again and again wanders, changing along the whole chain of memories; how a thought, born of the first sensation, leads to other thoughts, is carried away further and further ... ".

At the same time, it is indicative that in the late period of L. Tolstoy's work he puts forward the requirement of brevity. Since the 1990s, he strongly advises to carefully study the prose of A.S. Pushkin, especially Belkin's Tales. “The presentation always wins from the reduction,” he says to N.N. Gusev. The same interlocutor records an interesting statement by Tolstoy: “Short thoughts are good because they make you think. I don’t like some of my long ones, everything is chewed up in them too much. ”

Thus, in artistic speech, the stylistic use of complex syntactic constructions is largely due to the peculiarities of the individual author's writing style, although the "ideal" style seems to be laconic and "light"; it should not be overloaded with heavy complex structures.

39.Syntactic means of expressive speech

The syntactic means of creating expression are varied. These include those already considered by us - appeals, introductory and plug-in constructions, direct, improperly direct speech, many one-part and incomplete sentences, inversion as a stylistic device, and others. Stylistic figures, which are a strong means of emphatic intonation, should also be characterized.

Emphasis(from Greek. emphasis- indication, expressiveness) is an emotional, excited construction of oratory and lyrical speech. Various techniques that create emphatic intonation are predominantly characteristic of poetry and are rarely found in prose, and are designed not for visual, but for auditory perception of the text, which makes it possible to assess the rise and fall of the voice, the pace of speech, pauses, that is, all the shades of the sounding phrase. Punctuation marks can only conditionally convey these features of expressive syntax.

Poetic syntax is distinguished rhetorical exclamations, which contain a special expression, increasing the intensity of speech. For example, N.V. Gogol: Lush! He has no equal river in the world! (about the Dnieper). Such exclamations are often accompanied by hyperbole, as in the above example. Often they are combined with rhetorical questions: Troika! Three bird! Who made you up?.. Rhetorical question- one of the most common stylistic figures, characterized by remarkable brightness and a variety of emotionally expressive shades. Rhetorical questions contain a statement (or denial), framed as a question that does not require an answer: Weren't you at first so viciously persecuting His free, bold gift And for fun fanned the Slightly hidden fire?..

Coinciding in external grammatical design with ordinary interrogative sentences, rhetorical questions are distinguished by a bright exclamatory intonation, expressing amazement, extreme tension of feelings; It is no coincidence that authors sometimes put an exclamation point or two signs - a question mark and an exclamation point - at the end of rhetorical questions: Does her female mind, brought up in seclusion, doomed to alienation from real life, does she not know how dangerous such aspirations are and how they end??! (Bel.); And how is it that you still don’t understand and don’t know that love, like friendship, like salary, like glory, like everything in the world, must be deserved and supported?! (Good)

The rhetorical question, unlike many stylistic figures, is used not only in poetic and oratorical speech, but also in colloquial and journalistic texts, in artistic and scientific prose.

More rigorous, book coloring characterizes parallelism- the same syntactic construction of adjacent sentences or segments of speech:

The stars are shining in the blue sky

In the blue sea the waves are whipping;

A cloud is moving across the sky

The barrel floats on the sea.

(A.S. Pushkin)

Syntactic parallelism often reinforces rhetorical questions and exclamations, for example:

Poor criticism! She studied courtesy in girls' rooms, and acquired good manners in the hallways, is it any wonder that "Count Nulin" so cruelly offended her subtle sense of decency? (Bel.); Bazarov does not understand all these subtleties. How is it, he thinks, to prepare and attune oneself to love? When a person really loves, how can he be graceful and think about the little things of outward grace? Is real love fluctuates? Does she need any external aids of place, time and momentary disposition caused by conversation? (pis.)

Parallel syntactic constructions are often built according to the principle anaphora(unanimity). So, in the last of the examples we see an anaphoric repetition of the word unless, in Pushkin's poetic text of unity - in the blue sky... in the blue sea. A classic example of an anaphora is Lermontov's lines: I am the one to whom You listened in the midnight silence, Whose thought whispered to your soul, Whose sadness you vaguely guessed, Whose image you saw in a dream. I am the one whose gaze destroys hope; I am the one no one loves; I am the scourge of my earthly slaves, I am the king of knowledge and freedom, I am the enemy of heaven, I am the evil of nature...

Epiphora(ending) - the repetition of the last words of the sentence - also enhances the emphatic intonation: Why destroy the independent development of the child, violating his nature, killing his faith in himself and forcing him to do only what I want, and only the way I want, and only because I want? (Good)

Epiphora gives lyricism to Turgenev's prose poem "How good, how fresh were the roses ..."; this stylistic device was loved by S. Yesenin, let's remember his epiphora! - My white linden has faded, The nightingale dawn has rang... Nothing! I stumbled on a stone, It will all heal by tomorrow!; Foolish heart, don't beat; Concern lay in the misty heart. Why am I known as a charlatan? Why am I known as a brawler? That's why I'm known as a charlatan, That's why I'm known as a brawler. As seen from last example, the author can partly update the vocabulary of the epiphora, vary its content, while maintaining the external similarity of the statement.

Among the striking examples of expressive syntax are various ways proposal closure violations. Primarily, this offset syntactic construction : the end of the sentence is given in a different syntactic plan than the beginning, for example: And for me, Onegin, this splendor, Tinsel of a disgusting life, My successes in a whirlwind of light, My fashionable house and evenings, What is in them? (P.) The incompleteness of the phrase is also possible, as indicated by the author's punctuation: as a rule, this is an ellipsis - But those to whom in a friendly meeting I read the first stanzas ... There are no others, and those are far away, As Sadi once said(P.).

Punctuation allows the author to convey the discontinuity of speech, unexpected pauses, reflecting the emotional excitement of the speaker. Let's remember the words of Anna Snegina in S. Yesenin's poem! - Look... It's getting light. The dawn is like a fire in the snow... It reminds me of something... But what? dawn ... We were sitting together ... We are sixteen years old...

The emotional intensity of speech is conveyed by connecting structures, there are those in which phrases do not fit immediately into one semantic plane, but form an associative chain of attachment. Various methods of joining are provided by modern poetry, journalism, and fiction: Every city has an age and a voice. There are clothes. And a special smell. And a face. And not immediately understandable pride(R.); Quote on the 1st page. About personal. - I recognize the role of the individual in history. Especially if it's the president. Moreover, the President of Russia (V. Chernomyrdin's statement// News. - 1997. - January 29); Here I am in Bykovka. One. It's autumn outside. Late(Ast.). About such connecting structures, Professor N.S. Valgina notes: “Syntactically dependent segments of the text, but extremely independent intonationally, cut off from the sentence that gave rise to them, acquire greater expressiveness, become emotionally rich and vivid.”

Unlike connection structures, which are always postpositive, nominative representation(isolated nominative), naming the topic of the subsequent phrase and designed to arouse special interest in the subject of the statement, to enhance its sound, as a rule, comes first: My miller... Oh, that miller! He drives me crazy. Made a bagpipe, slacker, And runs like a postman(Es.). Another example: Moscow! How much has merged in this sound For the Russian heart, How much has resonated in it.! (P.) With such a peculiar emotional presentation of thought, it is separated by an emphatic pause; as noted by A.M. Peshkovsky, “... first an isolated object is put on display, and the listeners only know that something will be said about this object and that for the time being this object must be observed; in the next moment, the thought itself is expressed.

Ellipsis- this is a stylistic figure, consisting in the intentional omission of any member of the sentence, which is implied from the context: We sat down - in ashes, hailstones - in dust, in swords - sickles and plows(Bug.). The omission of the predicate gives speech a special dynamism and expression. This syntactic device must be distinguished from default- a turn of speech, consisting in the fact that the author deliberately does not complete the thought, giving the listener (reader) the right to guess which words are not spoken: No, I wanted... maybe you... I thought it was time for the baron to die.(P.). There is an unexpected pause behind the ellipsis, reflecting the speaker's excitement. As a stylistic device, default is often found in colloquial speech: - You can't imagine, this is such news!.. How do I feel now?.. I can't calm down.

The use of introductory words and phrases in speech requires a stylistic comment, since they, expressing certain evaluative meanings, give an expressive coloring to the statement and are often assigned to the functional style. Stylistically unjustified use of introductory words and phrases damages the culture of speech. Appeal to them may be associated with the aesthetic attitude of writers and poets. All this is of undoubted stylistic interest.

If we start from the traditional classification of the main meanings of the introductory components, it is easy to identify their types that are attached to one or another functional style. So, introductory words and phrases expressing reliability, confidence, assumption: undoubtedly, of course, probably, possibly - gravitate towards book styles.

Introductory words and phrases used to attract the attention of the interlocutor, as a rule, function in a colloquial style, their element is oral speech. But the writers, skillfully inserting them into the dialogues of the characters, imitate a casual conversation: - Our friend Popov is a nice fellow, - Smirnov said with tears in his eyes, - I love him, I deeply appreciate his talent, I am in love with him, but ... you know? - this money will ruin him (Ch.). Such introductory units include: listen, agree, imagine, imagine, do you believe, remember, understand, do me a favor and under. Abuse of them sharply reduces the culture of speech.

A significant group consists of words and phrases expressing an emotional assessment of the message: fortunately, to surprise, unfortunately, to shame, to joy, to misfortune, an amazing thing, a sinful thing, there is nothing to hide and under. Expressing joy, pleasure, chagrin, surprise, they give speech an expressive coloring and therefore cannot be used in strict texts of book speech, but are often used in live communication between people and in works of art.

Introductory sentences expressing roughly the same shades of meaning as introductory words, in contrast to them, are stylistically more independent. This is due to the fact that they are more diverse in terms of lexical composition and volume. But the main sphere of their use is oral speech (which introductory sentences are enriched intonation, giving it special expressiveness), as well as artistic, but not bookish styles, in which, as a rule, preference is given to shorter introductory units.

Introductory sentences can be quite common: While our hero, as they wrote in novels in the leisurely good old days, goes to the illuminated windows, we will have time to tell what a village party is (Sol.); but more often they are quite laconic: you know, you should notice, if I'm not mistaken, etc.

Plug-in words, phrases and sentences are additional, incidental remarks in the text.

Here are a few examples of the stylistically perfect inclusion of insert structures in a poetic text: Believe me (conscience is a guarantee), marriage will be torment for us (P.); When I begin to die, and, believe me, you will not have long to wait - you were led to transfer me to our garden (L.); And every evening, at the appointed hour (or is it just a dream of mine?), the girlish camp, seized with silks, moves in the foggy window (Bl.).

Golub I.B. Stylistics of the Russian language - M., 1997

Stylistic use of addresses

To create the emotionality of speech, writers can use words with bright expressive coloring as appeals: an autocratic villain; haughty descendants, figurative paraphrases: O Volga, my cradle, did anyone love you like I do? (N) In addition, epithets are often used when addressing, and they themselves are often tropes - metaphors, metonyms: Throw me, fire tower, to scare people (Bub.), Come here, beard! Their expression is emphasized by particles: Hey, coachman!; Come on, my friend; tautological combinations, pleonasms: Wind, wind, you are mighty (P.); Wind-wind!; Sea-Okian, finally, a special intonation - all this enhances the expressive power of this syntactic device in artistic speech.

However, appeals are sometimes needed in texts that are devoid of imagery and do not allow the use of expressive elements, in business correspondence, official documents addressed to certain individuals. But here the function of appeals is different: they play an informative role (indicate to whom the document is addressed), and also organize the text, acting as a kind of “beginning”.

In official business speech, stable combinations have been developed that serve as appeals in certain situations: dear sir, citizen, ladies and gentlemen, etc. Some of the previously used addresses are outdated: dear, venerable. The choice of the form of address in an official setting is important, since speech etiquette is an integral part of the culture of behavior, and in special situations it also acquires a socio-political connotation.

Stylistic use of introductory and insert structures

The use of introductory words and phrases in speech requires a stylistic comment, since they, expressing certain evaluative meanings, give an expressive coloring to the statement and are often assigned to the functional style. Stylistically unjustified use of introductory words and phrases damages the culture of speech. Appeal to them may be associated with the aesthetic attitude of writers and poets. All this is of undoubted stylistic interest.

Introductory words and phrases used to attract the attention of the interlocutor, as a rule, function in a colloquial style, their element is oral speech.

A significant group consists of words and phrases expressing an emotional assessment of the message: fortunately, to surprise, unfortunately, to shame, to joy, to misfortune, an amazing thing, a sinful thing, there is nothing to hide and under. Expressing joy, pleasure, chagrin, surprise, they give speech an expressive coloring and therefore cannot be used in strict texts of book speech, but are often used in live communication between people and in works of art.

Plug-in words, phrases and sentences are additional, incidental remarks in the text.

Stylistic use of the period. Stylistic functions of direct and improperly direct speech.

stylistic figures.

Stylistic figures

1) Anaphora (unity) is the repetition of individual words or phrases at the beginning of the passages that make up the statement.

I loveyou, Peter's creation,

I loveyour strict, slender look.(A.S. Pushkin)

2) Epiphora - making the same words or phrases at the end of adjacent verses, or stanzas, or prose paragraphs:

I would like to know why I am a titular councillor.? Why a titular adviser?(Gogol). Flows unceasingly rain, wearisome rain (V. Bryusov)

3) Antithesis - a pronounced opposition of concepts or phenomena. Antithesis contrasts different objects

Houses are new, but prejudices are old.(A. Griboedov).

4) Oxymoron - a combination of words that are directly opposite in meaning in order to show the inconsistency, complexity of the situation, phenomenon, object. An oxymoron attributes opposite qualities to one object or phenomenon.

There is happy melancholy in the scares of dawn.(S. Yesenin). It has come eternal moment . (A. Blok). Brazenly modest wild gaze . (Block) New Year I met one. I am rich, was poor . (M. Tsvetaeva) He's coming, saint and sinner, Russian miracle man! (Twardowski). Huge autumn, old and young, in the fierce blue radiance of the window.(A. Voznesensky)

5) Parallelism - this is the same syntactic construction of adjacent sentences or segments of speech.

Young everywhere we have a road, old people everywhere we honor(Lebedev-Kumach).

Knowing how to speak is an art. Listening is culture.(D. Likhachev)

6)gradation - this is a stylistic figure, consisting in such an arrangement of words, in which each subsequent contains an increasing (ascending gradation) or decreasing value, due to which an increase or weakening of the impression they produce is created.

BUT)I do not regret, do not call, do not cry ,

Everything will pass like smoke from white apple trees.(S. Yesenin).

AT senate give, ministers, sovereign» (A. Griboedov). "Not hour, not day, not year will leave"(Baratynsky). Look what house - big, huge, huge, straight up grandiose ! - the intonation-semantic tension is growing, intensifying - ascending gradation.

B)"Not a god, not a king, and not a hero"- words are arranged in order of weakening their emotional and semantic significance - descending gradation.

7)Inversion - this is the arrangement of the members of the sentence in a special order that violates the usual, so-called direct order, in order to enhance the expressiveness of speech. We can talk about inversion when stylistic tasks are set with its use - increasing the expressiveness of speech.

Amazingour people! hand gave me a goodbye.

8)Ellipsis - this is a stylistic figure, consisting in the omission of any implied member of the sentence. The use of an ellipsis (incomplete sentences) gives the statement dynamism, intonation of lively speech, and artistic expressiveness.

We villages - into ashes, cities - into dust, into swords - sickles and plows(Zhukovsky)

The officer - with a pistol, Terkin - with a soft bayonet.(Twardowski)

9)Default - this is a turn of speech, which consists in the fact that the author deliberately does not fully express the thought, leaving the reader (or listener) to guess what was not said.

No, I wanted... maybe you... I thought

It's time for the baron to die. ( Pushkin)

10)Rhetorical address - This is a stylistic figure, consisting in an underlined appeal to someone or something to enhance the expressiveness of speech. Rhetorical appeals serve not so much to name the addressee of the speech, but to express the attitude towards this or that object, to characterize it, to enhance the expressiveness of the speech.

Flowers, love, village, idleness, field!I am devoted to you soul(Pushkin).

11)Rhetorical question - this is a stylistic figure, consisting in the fact that the question is not posed in order to get an answer to it, but to draw the attention of the reader or listener to a particular phenomenon.

Do you know Ukrainian night?Oh, you don't know the Ukrainian night!(Gogol)

12)polyunion - a stylistic figure, consisting in the deliberate use of repeating unions and intonational underlining of the members of the sentence connected by unions, to enhance the expressiveness of speech.

A thin rain fell and to the forests and to the fields and on the wide Dnieper. ( Gogol) Houses burned at night and the wind was blowing and black bodies on the gallows swayed from the wind, and crows were crying over them(Kuprin)

13)Asyndeton - a stylistic figure consisting in the intentional omission of connecting unions between members of a sentence or between sentences: the absence of unions gives the statement swiftness, richness of impressions within the overall picture.

Swede, Russian - stabs, cuts, cuts, drumming, clicks, gnashing, thunder of cannons, stomping, neighing, moaning ...(Pushkin)

Stylistic mistakes.

The use of a word in an unusual sense: To be literate and have great jargon words, you need to read a lot. -To be literate and have a great reserve words, you need to read a lot.

Violation of lexical compatibility: cheap prices vm. low prices

Use of an extra word (pleonasm): Arrived feathered birds vm. The birds have arrived

The use of words next to or close to each other in a sentence (tautology): story"Mu Mu" tells... vm. The story "Mumu" tells...

Lexical repetitions in the text.

The use of a word (expression) of inappropriate stylistic coloring. So, in a literary context, the use of jargon, vernacular, abusive vocabulary is inappropriate; in a business text, colloquial words, expressively colored words should be avoided.

Mixing vocabulary from different historical eras: On the heroes of chain mail, trousers, mittens.On the heroes of chain mail, armor, gloves.

Poverty and monotony of syntactic constructions. The man was dressed in a burnt padded jacket. The quilted jacket was roughly darned. The boots were almost new. Moth-eaten socks The man was dressed in a roughly darned burnt padded jacket. Although the boots were almost new, the socks were moth-eaten.

Unfortunate word order. There are many works that tell about the author's childhood in world literature. In world literature there are many works that tell about the author's childhood.

Stylistic and semantic inconsistency between the parts of the sentence. The red-haired, fat, healthy, with a shiny face, singer Tamagno attracted Serov as a person of great internal energy. , with a splashing health face.

1. The concept of style. The subject and tasks of practical and functional stylistics.

2. The concept of functional styles. Features of the scientific style.

3. Styles of fiction. Lexical, morphological, syntactic features of style.

4. Journalistic style, its genres. Lexical, morphological, syntactic features of style.

5. Official business style: lexical, morphological, syntactic features of style.

6. Features of conversational style: lexical, morphological, syntactic.

7. Stylistic functions of synonyms, antonyms.

8. Stylistic properties of words associated with their assignment to the active or passive composition of the language.

9. Stylistic properties of words related to the scope of their use.

10. Stylistic use of phraseological means of the language.

11. Figurative means of speech (epithet, metaphor, comparison, etc.).

12. The use of the singular of a noun in the meaning of the plural. The use of abstract, material and proper nouns in the plural.

13. Stylistic use of nouns: gender differences in personal nouns.

14. Stylistic use of noun gender forms. Hesitation in the gender of nouns. The gender of indeclinable nouns.

15. Stylistic characteristics of variants of case forms. Variants of the endings of the genitive case of the singular masculine nouns.

16. Stylistic characteristics of variants of case forms. Variants of the endings of the prepositional case of the singular of masculine nouns.

17. Stylistic characteristics of variants of case forms. Variants of forms of the accusative case of animate and inanimate nouns.

18. Stylistic use of the adjective. Synonymy of full and short forms of adjectives.

19. Stylistic features of the declension of names and surnames.

20. Stylistic features of numerals. Variants of combinations of numerals with nouns.

21. Collective and cardinal numbers as synonyms.

22. Stylistic use of personal pronouns.

23. Stylistic use of reflexive and possessive pronouns.

24. Stylistic features of the formation of some personal forms of the verb. Synonymy of reflexive and non-reflexive forms of the verb.

25. Variants of forms of participles and participles. Stylistic use of adverbs.

26. Syntactic and stylistic meaning of word order. The place of the subject and predicate.

27. Predicate with subject type brother and sister.

28. Predicate with a subject expressed by interrogative, relative, indefinite pronouns.

29. Predicate with a subject, expressed by a quantitative-nominal combination.

30. Coordination of the predicate with the subject, which has an application with it.

31. Coordination of the link with the nominal part of the compound predicate. A predicate with a subject expressed by an indeclinable noun, a complex abbreviated word, an inseparable group of words.

32. Stylistic assessment of the agreement of the predicate with the subject, which includes a collective noun.

33. Stylistic features of the agreement of the predicate with homogeneous subjects.

34. Place of definition, additions and circumstances in the proposal.

35. Coordination of definitions with nouns depending on numerals two three four.

36. Agreement of definition with a noun of general gender and with a noun that has an application.

37. Variants of case forms of the object with transitive verbs with negation.

38. Synonymy of non-prepositional and prepositional constructions.

39. Stylistic features of constructions with verbal nouns. Stringing cases.

40. Stylistic features of management with synonymous words. Management with homogeneous members of the proposal.

41. Stylistic functions of homogeneous members. Unions with homogeneous members.

42. Errors in combinations of homogeneous members.

43. Stylistic use different types simple suggestion.

44. Stylistic use of different types of compound sentences.

45. Errors in complex sentences.

46. general characteristics parallel syntactic constructions.

47. Stylistic use of participles and adverbs.

48. Stylistic use of appeals, introductory and plug-in structures.

49. Stylistic use of the period. Stylistic functions of direct and improperly direct speech.

50. Stylistic figures.

IV. Stylistic functions of insert structures

Plug-in structures that have a semantic capacity (introduce additional information, additional explanations, clarifications, amendments, remarks) are used in various speech styles. Widely used in colloquial speech and in the language of works of art:

It is most prudent and safest to expect a siege inside the city, and to repel an enemy attack by artillery and (if possible) sorties. (A. Pushkin.)

Conclusion:

In works of art, introductory words, phrases, sentences, plug-in constructions are often used, which allow expressing the speaker's attitude to the thought being expressed, drawing attention to what is being reported, making the speech expressive, figurative, as well as adding remarks and explanations to the sentence.

V. Fixing the material

Ex. 410. D. E. Rosenthal. Russian language. 10-11 cells.

Find introductory words and sentences in the text. Explain their function.

Homework

1. Run exercise. 408. D. E. Rosenthal. Russian language. 10-11 cells.

2. Repeat punctuation for calls; isolation of interjections and words-sentences.

Lesson 14 (26-27)

Punctuation when addressing.

Word-sentences and the selection of interjections in speech

The purpose of the lesson:

Repetition and generalization of students' knowledge about constructions that are not grammatically related to the sentence, the formation of the skill to correctly punctuate these constructions in writing.

During the classes

I. Verification work

Ex. 23-5 (A. I. Vlasenkov, L. M. Rybchenkova. Russian language. 10-11 grades)

Write off the text, inserting the missing punctuation marks.

Additional tasks. Make a syntactic analysis of the selected sentence, write out all the phrases, indicate the method of communication. Write out words that are not grammatically related to the members of the sentence.

(The work is done on sheets of paper and evaluated by the teacher.)

II. Repetition of theoretical material on the topic "Appeal"

What is an appeal?

What is a rhetorical appeal? ( Rhetorical appeals convey expressive-emotional relationships: Noise, noise, obedient sail, worry under me, gloomy ocean.(A. Pushkin.))

What stylistic varieties of appeals do you still know? Appeals - metaphors:

Listen, graveyard of laws, as the general calls you...

Appeals - metonymy:

Death, but Death, will you let me say one more word there? (A. Tvardovsky.)

Appeals - ironies:

Where, smart, are you wandering, head? (I. Krylov.)

Inversions - repetitions:

Hello, wind, formidable wind, tailwind world history! (L. Leonov.)

Folklore appeals:

Forgive me, farewell, cheese-dense forest, with a summer will, with a winter blizzard! (A. Koltsov.)

Appeals - proverbs:

Fathers, matchmakers, take out, holy saints! (N. Gogol.)

What appeals are typical for colloquial speech and how are they expressed?

For colloquial speech, for common speech, characteristic appeals expressed by pronouns of the 2nd person:

Well, you move, otherwise you'll be late!

Conversations in truncated form without ending:

Tanya, let's go to the library?

Appeals, which are a combination of a definition with a defined word, between which there is a pronoun of the 2nd person:

Isn't it enough for you, you insatiable kind! (F. Dostoevsky.)

- What punctuation marks separate appeals? (References are usually separated by commas.)

If the appeal is pronounced with special force (intonation), then an exclamation mark may be placed after it. After it, the sentence continues with a capital letter:

Dear, respected closet! I welcome your existence. (A. Chekhov.)

III. Anchoring

Ex. 402 (D. E. Rozental. Russian language. 10-11 grades) The teacher dictates sentences (1, 3, 5, 9, 10, 13, 15), then the students explain the punctuation marks and stylistic functions of the addresses, followed by self-examination on textbook.

IV. Acquaintance with theoretical material on the topic "Punctuation marks for interjections and sentence words"

1. The interjection is separated from the sentence following it with a comma if it is pronounced without an exclamatory intonation:

Bravo, Vera! Where did you get this wisdom? (I. Goncharov.) How I love the sea, oh, how I love the sea! (A. Chekhov.)

2. If the interjection is pronounced with an exclamatory intonation, then an exclamation mark is placed after it. If the interjection is at the beginning of a sentence, then the word following it is written with a capital letter, and if in the middle, then with a lowercase letter:

“U! Minion! the nanny grumbles softly. (I. Goncharov.) Marya, you know, is generous and working, wow! angry! (N. Nekrasov.)

3. It is necessary to distinguish between interjections and identically sounding particles: after interjections, a comma is placed, after particles - no:

Well, let's dance! (N. Ostrovsky.) Well, how not to please your dear little man! (A. Griboyedov.)

4. The comma is not placed inside whole combinations oh you, wow, oh you, oh yes, oh these etc., which include interjections and pronouns or particles:

Oh yes, Mikhail Andreevich, a real gypsy! (A. Tolstoy.)

5. Interjections before words are not separated by a comma how, what and in combination with them expressing a high degree of a sign (in the meanings of “very”, “very”, “wonderful”, “amazing”, “terrible”)

Property, therefore, recognizes; and this, at the present time, oh, how nice! (M. S.-Shchedrin.)

6. Sentence words Yes and No are separated from the sentence revealing their meaning by a comma or an exclamation mark:

No, I will never leave you! Not! You really listen. (L. Tolstoy.)

Particle about standing at the words-sentences Yes and No, a comma is not separated from them:

Oh no, the fog is whitening over the water. (V. Zhukovsky.)

V. Consolidation of the studied

Ex. 391. Letter of comment

Rewrite the sentences, fill in the missing punctuation marks. (Students do the work in a notebook, one of the students, at the choice of the teacher, comments on the punctuation marks.)

VI. Summing up the lesson

Talk about writing interjections.

What are the features of punctuation of words-sentences Yes and No.

Homework

1. Run exercise. 392, 393. (V. F. Grekov, S. E. Kryuchkov, L. A. Cheshko.)

2. Repeat the spelling of checked and unchecked unstressed vowels.

Lesson 15 (28)

Order of words in a sentence

The purpose of the lesson:

To reveal the stylistic functions of word order in a sentence.

During the classes

I. Test dictation

The text is recorded under the dictation of the teacher, the students perform a graphical analysis of punctuation marks and the most significant, from their point of view, spelling.

The purpose of the task is to teach to check the text. (Works are checked by the teacher.)

1. So, as stated above, over the years I have not become important. (A. Tvardovsky.) 2. And only Bryantsev, as it seemed to him, for the first time saw the regiment commander as he is in all spiritual nakedness: both powerful, and hot, and formidable. (M. Bubennov.) 3. The coniferous ocean whipped human life, even hunters - and there are many of them in this region - feel like guests in the forest, do not dare to leave the roads far. (V. Tendryakov.) 4. But Petya, no matter how he squinted, no matter how hard he strained his eyes, to be honest, he did not see anything in the desert of the sea. (V. Kataev.) 5. In one case, he admired her amazing ability to make acquaintances with extraordinary ease and immediately like everything with her simplicity and inexhaustible gaiety; in another case, courage in solving the various questions posed by life; in the third - her fearless riding a motorcycle, contempt for danger; and in many other cases, her happy, melodious voice, affectionately mischievous smile and sultry, radiant, sea-blue eyes. (M. Bubennov.) 6. How good you are, O night sea! (F. Tyutchev.) 7. And the forest was really noisy, oh, and it was noisy! (V. Korolenko.) 8. Well, - he thoughtfully replied, - they are people like people. They love money, but it has always been... Well, they are frivolous... well, well... and mercy sometimes knocks on their hearts... In general, they remind the former ones... housing problem only spoiled them... (M. Bulgakov.) 9. "Yes, I don't like the proletariat," Philipp Philippovich agreed sadly. (M. Bulgakov.)

Select and write down 10 words for the spelling of checked unstressed vowels and 10 words for the spelling of unchecked unstressed vowels at the root of the word.

II. Syntactic and stylistic meaning of word order

Knowledge update

What do you know about word order in a Russian sentence? (In a Russian sentence, word order is considered free.)

What changes does the permutation of the members of the sentence entail? (Any rearrangement of the members of a sentence is associated with a greater or lesser change in its meaning or in the stylistic shades of the utterance.)

What role does word order play in a sentence and what does word order depend on? (Syntactic and stylistic. Word order depends on the purpose of the statement.)

Offer analysis.

1. I met my brother's teacher. - I met the teacher's brother.

2. Moscow is the capital of Russia. The capital of Russia is Moscow.

3. Our task is to learn. - Learning is our task.

4. Brother returned sick. The sick brother is back.

What changes did you notice as a result of rearranging the words in the sentence? (The meaning of the sentences has changed. This is due to a change syntactic role a permuted member of the sentence: in the first pair, as a result of the permutation, the addition of “teacher” became an inconsistent definition, and the inconsistent definition of “brother” became an addition; in the second and third pairs, the predicate and the subject "swapped" places; in the fourth pair, the word "sick", which forms the nominal part of the compound predicate, began to play the role of a definition.)

What conclusion can be drawn? (Word order is syntactic.)

What do you know about forward and backward word order? What stylistic function do they perform in a sentence, in context?

The reverse order (inversion nature) of the sentence is determined by the place of the word in the sentence and the position of the interconnected members of the sentence in relation to each other. The winning, significant part of the sentence is the one that is placed at the beginning or, conversely, is moved to the end of the sentence:

His sharpness and subtlety of instinct struck me. (A. Pushkin.) The Dnieper is wonderful in calm weather ... (N. Gogol.) He gladly accepted this news.

- Name the scope of use of sentences with direct and reverse word order. (The direct order is typical for scientific and journalistic speech, the reverse order is more often used in colloquial speech and in works of fiction.)

Is reverse word order always justified in a sentence? (Inversion contains rich stylistic possibilities, but they must be skillfully used. According to A. M. Peshkovsky, if the direct word order is perceived as the norm, then the stylistic use of the reverse order should be aesthetically justified. Unjustified inversion leads to stylistic errors, distortion of meaning phrases or ambiguity.)

III. Offer analysis

Identify stylistic flaws, correct sentences.

1. On the stands ... posters and posters about the performances of I. Ehrenburg in German, French, Czech, Polish and other languages.

(I meant posters and posters on different languages, not the writer's speech.)

2. The second group of the IV course, where the headman Nina Petrova, did a good job of practicing, which this year has significantly increased in its volume compared to last year.

(We are talking about increasing practice, the meaning is distorted due to unfortunate word order.)

3. The best milkmaid Kozlova MP on the 28th day after calving received 37 liters of milk from a cow named Maruska.

(The words on the 28th day after calving should have been put after the word Maruska.)

- Determine the stylistic load of the word at the beginning and at the end of the sentence.

1. He looked around him with indescribable excitement. 2. A light shone dimly from one window. 3. Fate's sentence has come true. 4. Then my friend burned out of shame. 5. The denouement came unexpectedly. 6. A blindingly bright flame escaped from the furnace. 7. On the extreme alley to the steppe, on a January evening in 1930, a horseman rode into the Gremyachiy Log farm.

IV. Summing up the lesson

What role does word order play in a sentence?

What is the stylistic function of reverse word order?

Homework

1. Prepare for control work. Revise the studied material on the syntax of a simple sentence.

2. Task for the future;

a) repeat the spelling of derivative prepositions;

b) prepare a short report on clericalism.

Teacher material

Chancellery- words and expressions of official business speech used outside of it. Chancery deprive speech of the necessary simplicity, liveliness, emotionality, give it a "official" character. It is necessary to distinguish between the concepts of "clerical language" (dry, official speech, devoid of cash colors, inexpressive) and "official business style" (a kind of literary language, the language of contracts and laws, official documents, etc.)

You see, excuse the expression, what a circumstance, by the way. (A. Chekhov.)

Do not enrich speech and pleonasms (verbosity, excess of speech): his autobiography(the word “autobiography” already contains the concept of “one’s own”), meet for the first time in March and etc.

Thus, justified to a certain extent in official business speech, clericalisms turn out to be inappropriate in other speech systems, where their use is not associated with a stylistic intention.

Lessons 16-17 (29-30)

Control work and its analysis. Work on mistakes

The purpose of the lesson:

Checking students' knowledge.

Dictation

1. Find constructions that complicate a simple sentence. Describe them.

2. Parse the sentences.

Option I

Leo Tolstoy is the most popular of modern Russian writers, and War and Peace, one can safely say, is one of the most remarkable books of our time. This extensive work is fanned with an epic spirit; in it, the private and public life of Russia in the first years of our century is depicted by the hand of a true master. A whole era passes before the reader, rich in great events and major figures (the story begins shortly before the battle of Austerlitz and reaches the battle near Moscow), a whole world arises with many types snatched straight from life, belonging to all strata of society. The way in which Count Tolstoy develops his theme is as new as it is peculiar; it is not the method of Walter Scott and, of course, not the manner of Alexandre Dumas either. Count Tolstoy is a Russian writer to the marrow of his bones, and those French readers who are not repulsed by the few lengths and originality of certain judgments will have the right to say to themselves that War and Peace has given them a more direct and true idea of the character and temperament of the Russian people and of Russian life in general than if they had read hundreds of works on ethnography and history. There are whole chapters here in which nothing will ever have to be changed; here are historical figures (like Kutuzov, Rostopchin and others), whose features are established forever. This is the enduring... This is a great work of a great writer - and this is true Russia. (200 words)

(I. S. Turgenev)

Option II

Inspiration is a strict working state of a person. Spiritual uplift is not expressed in a theatrical pose and elation. As well as the notorious "torments of creativity."

Tchaikovsky argued that inspiration is a state when a person works with all his strength, like an ox, and does not at all coquettishly wave his hand.

Each person, at least several times in his life, has experienced a state of inspiration - spiritual uplift, freshness, a vivid perception of reality, the fullness of thought and consciousness of his creative power.

Yes, inspiration is a strict working state, but it has its own poetic coloring, its own, I would say, poetic subtext.

Inspiration enters us like a radiant summer morning that has just thrown off the mists of a quiet night, spattered with dew, with thickets of wet foliage. It gently breathes its healing coolness into our faces.

Inspiration is like first love, when the heart beats loudly in anticipation of amazing meetings, unimaginably beautiful eyes, smiles and omissions.

Then our inner world is finely tuned and true, like a kind of instrument, and responds to everything, even the most hidden, most inconspicuous sounds of life.

Many excellent lines have been written about inspiration by writers and poets. Turgenev called inspiration "the approach of God", the enlightenment of man by thought and feeling.

Tolstoy said about inspiration, perhaps most simply: “Inspiration consists in the fact that something that can be done suddenly opens up.” The brighter the inspiration, the more painstaking work should be for its execution. (210 words)