What forms of government did Thomas Aquinas distinguish? About the reign of sovereigns

"ON THE GOVERNMENT OF STATES" *

Thomas Aquinas (1226 - 1274) - the main representative of medieval Catholic theology and scholasticism. In 1323 he was canonized as a saint, and in 1879 his teaching was declared the “only true” philosophy of Catholicism. The state, according to the teachings of Thomas Aquinas, is a part of the universal order, the ruler of which is God.

· “... The goal is to achieve heavenly bliss through a virtuous life ... To lead to this goal is the appointment of not earthly, but divine power”

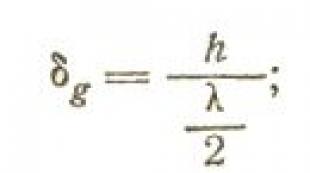

... If an unjust government is administered by only one who seeks to extract his interest from the government, and not at all the benefit for the multitude subject to him, such a ruler is called a tyrant (which name is derived from “strength”), because, as you know, he oppresses with power, and does not rule with justice, which is why among the ancients powerful people were called tyrants. If an unjust government is administered not by one person, but ... by a few - it is called an oligarchy, that is, it is the rule of a few, when, as you know, a few suppress the plebs for the sake of enrichment, differing from a tyrant only in quantity. If the unjust government is carried out by many, this is called democracy, which means the dominance of the people, when people from the common people suppress the rich. Thus, the whole people acts as one tyrant. Just government should be distinguished in the same way. So, if the government is carried out by some kind of multitude, this is called “polity”, for example, when a multitude consisting of warriors dominates a city-state or province. If management is carried out by a few, but possessing excellent qualities, people, this kind of government is called "aristocracy", that is, the best power, or the power of the best, those who are therefore called optimates. If just government is exercised by one, he is rightly called a king. …

Some of those who go to the goal manage to achieve it directly, and someone indirectly. Therefore, in the direction of the multitude, just and unjust meet. All government is direct when it leads to a proper end, and indirect when it leads to an improper one. Many freemen and many slaves serve different purposes. For he is free who is his own cause, but a slave is he who is what he is by the cause of another. So, if a multitude of free people is directed by a ruler for the common good of this multitude, this government is direct and just, as befits the free. If the government is directed not to the common good of the multitude, but to the personal good of the ruler, this government is unjust and perverted. …

So one governs better than many, because they are only getting closer to becoming one. Moreover, what exists by nature is arranged in the best way, because nature in each individual case acts in the best way, and the general government in nature is carried out by one. Indeed, among the many parts of the body, there is one that moves everything, namely the heart, and among the parts of the soul, one force predominates, namely the mind. After all, the bees have one king, and in the whole universe there is one God, the creator of everything and the ruler. And this is reasonable. Verily, every multitude comes from one. Therefore, if what comes from art imitates what comes from nature, and the work of art is the better, the closer it approaches what exists in nature, then it inevitably follows that that human multitude is best governed, which manages one. …

Moreover, a united force is more effective in accomplishing what is intended than a scattered or divided one. After all, many, united together, are pulling what they cannot pull out one by one if the load is divided among each. Therefore, how much more beneficial it is when the power that works for good is more united, since it is directed towards doing good, so much more harmful if the power that works for evil is one, and not divided. The power of the wicked ruler is directed to the evil of the multitude, since he will turn the common good of the multitude only into his own good. So, the more united the government, under a just government, the more useful it is; thus a monarchy is better than an aristocracy, and an aristocracy is better than a polity. For unjust government, the opposite is true - so, obviously, the more united the government, the more pernicious it is. So, tyranny is more pernicious than oligarchy, and oligarchy than democracy. …

So people unite in order to live well together, which no one can achieve by living alone; but the good life follows virtue, for the virtuous life is the goal of human union. ... But to live following virtue is not the ultimate goal of the united multitude, the goal is to achieve heavenly bliss through a virtuous life. ... Leading to this goal is the appointment of not earthly, but divine power. This kind of authority belongs to the one who is not only a man, but also God, namely our Lord Jesus Christ...

So, the service of his kingdom, since the spiritual is separated from the earthly, was entrusted not to earthly rulers, but to priests, and especially to the high priest, the successor of Peter, the vicar of Christ, the Pope of Rome, to whom all the kings of the Christian world must obey, as to the Lord Jesus Christ himself. For those to whom the care of the anterior ends belongs must obey him to whom the care of the final goal belongs, and recognize his authority.

Four mnemonic rules, five proofs that God exists, the problems of theology, the superiority of spoken language over writing, the reasons why the activities of the Dominicans make sense and other important discoveries, as well as facts about the biography of the Sicilian Bull

Prepared by Svetlana Yatsyk

Saint Thomas Aquinas. Fresco by Fra Bartolomeo. Around 1510-1511 Museo di San Marco dell "Angelico, Florence, Italy / Bridgeman Images

1. On the origin and disadvantageous relationship

Thomas Aquinas (or Aquinas; 1225-1274) was the son of Count Landolfo d'Aquino and nephew of Count Tommaso d'Acerra, Grand Justiciar of the Kingdom of Sicily (that is, the first of the royal advisers in charge of court and finance), and second cousin of Frederick II Staufen . Kinship with the emperor, who, seeking to subjugate all of Italy, constantly fought with the popes of Rome, could not but do a disservice to the young theologian - despite the open and even demonstrative conflict of Aquinas with his family and the fact that he joined the Dominican order loyal to the papacy . In 1277, part of Thomas's theses was condemned by the Bishop of Paris and the Church, apparently mainly for political reasons. Subsequently, these theses became generally accepted.

2. About the school nickname

Thomas Aquinas was distinguished by his tall stature, heaviness and sluggishness. It is also believed that he was characterized by meekness, excessive even for monastic humility. During the discussions led by his mentor, the theologian and Dominican Albertus Magnus, Thomas rarely spoke out, and other students laughed at him, calling him the Sicilian Bull (although he was from Naples, not Sicily). Albert the Great is credited with a prophetic remark, allegedly uttered to pacify the students teasing Thomas: “Do you call him a bull? I tell you, this bull will roar so loudly that its roar will deafen the world.”

Posthumously, Aquinas was awarded many other, more flattering nicknames: he is called the “angelic mentor”, the “universal mentor” and the “prince of philosophers”.

3. About mnemonic devices

Early biographers of Thomas Aquinas claim that he had an amazing memory. Even in his school years, he memorized everything that the teacher said, and later, in Cologne, he developed his memory under the guidance of the same Albert the Great. The collection of sayings of the Church Fathers on the four Gospels, which he prepared for Pope Urban, was compiled from what he memorized by looking through, but not transcribing, manuscripts in various monasteries. His memory, according to contemporaries, possessed such strength and tenacity that everything that he happened to read was preserved in it.

Memory for Thomas Aquinas, as for Albertus Magnus, was part of the virtue of prudence, which had to be nurtured and developed. To do this, Thomas formulated a number of mnemonic rules, which he described in a commentary on Aristotle's treatise "On Memory and Remembrance" and in "The Sum of Theology":

- The ability to remember is located in the "sensitive" part of the soul and is associated with the body. Therefore, "sensible things are more accessible to human knowledge." Knowledge that is not associated "with any bodily likeness" is easily forgotten. Therefore, one should look for “symbols inherent in those things that need to be remembered. They should not be too famous, because we are more interested in unusual things, they are more deeply and clearly imprinted in the soul.<…>Following this, it is necessary to come up with similarities and images. Summa Theologiae, II, II, quaestio XLVIII, De partibus Prudentiae..

“Memory is under the control of reason, so the second mnemonic principle of Thomas is “to arrange things [in memory] in a certain order so that, remembering one feature, you can easily move on to the next.”

- Memory is associated with attention, so you need to "feel attached to what needs to be remembered, because what is strongly imprinted in the soul does not slip out of it so easily."

- And finally, the last rule is to regularly reflect on what needs to be remembered.

4. On the relationship between theology and philosophy

Aquinas distinguished three types of wisdom, each of which is endowed with its own "light of truth": the wisdom of Grace, theological wisdom (the wisdom of revelation, using the mind) and metaphysical wisdom (the wisdom of the mind, comprehending the essence of being). Proceeding from this, he believed that the subject of science is the "truths of reason", and the subject of theology is the "truths of revelation."

Philosophy, using its rational methods of cognition, is able to study the properties of the surrounding world. Articles of faith proved by rationalized philosophical arguments (for example, the dogma of the existence of God) become more understandable to man and thereby strengthen him in faith. And in this sense, scientific and philosophical knowledge is a serious support in substantiating the Christian doctrine and refuting criticism of faith.

But many dogmas (for example, the idea of the createdness of the world, the concept of original sin, the incarnation of Christ, the resurrection from the dead, the inevitability of the Last Judgment, etc.) are not amenable to rational justification, since they reflect the supernatural, miraculous qualities of God. The human mind is not able to comprehend the divine plan in full, therefore, true, higher knowledge is not subject to science. God is the lot of supramental knowledge and, therefore, the subject of theology.

However, for Thomas there is no contradiction between philosophy and theology (just as there is no contradiction between the “truths of reason” and the “truths of revelation”), since philosophy and knowledge of the world lead a person to the truths of faith. Therefore, in the view of Thomas Aquinas, studying the things and phenomena of nature, a true scientist is right only when he reveals the dependence of nature on God, when he shows how the divine plan is embodied in nature.

Saint Thomas Aquinas. Fresco by Fra Bartolomeo. 1512 Museo di San Marco dell"Angelico

Saint Thomas Aquinas. Fresco by Fra Bartolomeo. 1512 Museo di San Marco dell"Angelico 5. About Aristotle

Albert the Great, the teacher of Thomas Aquinas, was the author of the first commentary written in Western Europe on Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. It was he who introduced the writings of Aristotle into use in Catholic theology, previously known in the West mainly in the exposition of the Arab philosopher Averroes. Albert showed the absence of contradictions between the teachings of Aristotle and Christianity.

Thanks to this, Thomas Aquinas got the opportunity to Christianize ancient philosophy, primarily the works of Aristotle: striving for a synthesis of faith and knowledge, he supplemented the doctrinal dogmas and religious and philosophical speculations of Christianity with socio-theoretical and scientific reflection based on the logic and metaphysics of Aristotle.

Thomas was not the only theologian who tried to appeal to the writings of Aristotle. The same was done, for example, by his contemporary Seeger of Brabant. However, Seeger's Aristotelianism was considered "Averroist", retaining some of the ideas introduced into the writings of Aristotle by his Arabic and Jewish translators and interpreters. The "Christian Aristotelianism" of Thomas, based on the "pure" teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher, which did not contradict Christianity, won - and Siger of Brabant was put on trial by the Inquisition for his convictions and killed.

6. About the conversational genre

Answering the question why Christ preached, but did not write down the postulates of his teaching, Thomas Aquinas noted: "Christ, addressing hearts, put the word above the scripture" Summa Theologiae, III, quaestio XXXII, articulus 4.. This principle was generally popular in the 13th century: even the system of scholastic university teaching was based on quaestio disputata, discussion on a given problem. Aquinas wrote most of his works in the genre of "sum" - a dialogue consisting of questions and answers, which seemed to him the most accessible for students of theology. The Summa Theologia, for example, a treatise he wrote in Rome, Paris, and Naples between 1265 and 1273, consists of chapters, articles, in the title of which is a controversial issue. Thomas gives several arguments to each, giving different, sometimes opposite answers, and at the end he gives counterarguments and the correct, from his point of view, decision.

7. Evidence for the existence of God

In the first part of The Sum of Theology, Aquinas substantiates the need for theology as a science with its own purpose, subject and method of research. He considers the root cause and the ultimate goal of all that exists, that is, God, to be its subject. That is why the treatise begins with five proofs of the existence of God. It is thanks to them that the Summa Theology is primarily known, despite the fact that out of the 3,500 pages that this treatise occupies, only one and a half are devoted to the existence of God.

First proof the existence of God relies on the Aristotelian understanding of motion. Thomas states that "everything that moves must be moved by something else" Here and below: Summa Theologiae, I, quaestio II, De Deo, an Deus sit.. An attempt to imagine a series of objects, each of which makes the previous one move, but at the same time is set in motion by the next one, leads to infinity. An attempt to imagine this must inevitably lead us to the understanding that there was a certain prime mover, "who is not driven by anything, and by him everyone understands God."

Second proof slightly reminiscent of the first and also relies on Aristotle, this time on his doctrine of four causes. According to Aristotle, everything that exists must have an active (or generative) reason, that from which the existence of a thing begins. Since nothing can produce itself, there must be some first cause, the beginning of all beginnings. This is God.

Third proof the existence of God is a proof "from necessity and chance." Thomas explains that among entities there are those that may or may not be, that is, their existence is accidental. There are also necessary entities. “But everything necessary either has a reason for its necessity in something else, or it does not. However, it is impossible that [a series of] necessary [existing] having a reason for their necessity [in something else] goes to infinity. Therefore, there is a certain essence, necessary in itself. This necessary entity can only be God.

Fourth proof“comes from the degrees [of perfections] found in things. Among things, more and less good, true, noble, and so on are found. However, the degree of goodness, truth and nobility can only be judged in comparison with something "the most true, best and noblest." God has these properties.

In the fifth proof Aquinas again relies on Aristotle's doctrine of causes. Based on the Aristotelian definition of expediency, Thomas states that all objects of being are directed in their existence towards some goal. At the same time, "they achieve the goal not by chance, but intentionally." Since the objects themselves are "devoid of understanding", therefore, "there is something thinking, by which all natural things are directed towards [their] goal. And this is what we call God.

8. About the social system

Following Aristotle, who developed these questions in Politics, Thomas Aquinas reflected on the nature and character of the sole power of the ruler. He compared royal power with other forms of government and, in accordance with the traditions of Christian political thought, spoke unambiguously in favor of the monarchy. From his point of view, the monarchy is the most just form of government, certainly superior to the aristocracy (the power of the best) and polity (the power of the majority in the interests of the common good).

Thomas considered the most reliable type of monarchy to be elective, not hereditary, since electivity can prevent the ruler from turning into a tyrant. The theologian believed that a certain set of people (he probably meant bishops and part of the secular nobility participating in the election of secular sovereigns, primarily the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and the pope) should have the legal opportunity not only to give the king power over themselves, but and deprive him of this power if it begins to acquire the features of tyranny. From the point of view of Thomas Aquinas, this "multiple" should have the right to deprive the ruler of power, even if they "previously submitted themselves to him forever", because the bad ruler "transcends" his office, thereby violating the terms of the original contract. This idea of Thomas Aquinas subsequently formed the basis of the concept of "social contract", which is very significant in modern times.

Another way to combat tyranny, which was proposed by Aquinas, makes it possible to understand on which side he was in the conflict between the empire and the papacy: against the excesses of a tyrant, he believed, the intervention of someone standing above this ruler could help - which could easily be interpreted contemporaries as an endorsement of the intervention of the pope in the affairs of "bad" secular rulers.

9. About indulgences

Thomas Aquinas resolved a number of doubts related to the practice of granting (and buying) indulgences. He shared the concept of the "treasury of the church" - a kind of "surplus" stock of virtues replenished by Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and the saints, from which other Christians can draw. This "treasury" can be disposed of by the Pope of Rome, issuing special, legal in nature acts - indulgences. Indulgences only work because the holiness of some members of the Christian community outweighs the sinfulness of others.

10. About the Dominican mission and preaching

Although the Dominican order was founded by Saint Dominic in 1214, even before the birth of Aquinas, it was Thomas who formulated the principles that became the rationale for their activities. In The Sum Against the Gentiles, the theologian wrote that the path to salvation is open to everyone, and the missionary's role is to give a particular person the knowledge necessary for his salvation. Even a wild pagan (whose soul strives for good) can be saved if the missionary manages to convey to him the saving divine truth.

Keywords

Aquinas / De regimine / authorship / dating / Lord / Prince / rulerannotation scientific article on philosophy, ethics, religious studies, author of scientific work - Alexander Marey

The article is an introduction to the translation into Russian of the first book of the treatise "De regimine principum". It examines the place of the treatise in the tradition of the "rulers' mirror", provides a brief analysis of the problems of authorship and dating of the treatise. Within the framework of the European tradition of mirrors of rulers, the work of Thomas Aquinas "On the reign of princes" occupies a special place. Certainly not the first in the tradition, this text has become one of the best known in the genre. According to his model, the treatises of the same name by Ptolemy of Lucca and Aegidius of Rome were written. In the discussion about dating, the author is of the opinion that the treatise was written in 1271-1273, and the King of Cyprus Hugo III Lusignan was its addressee. Separate place the article is devoted to the discussion about the principles of translation, centered around the approaches to the translation of the main categories of the political philosophy of Aquinas, first of all - princeps. An opinion is expressed about the impossibility of translating it with the Russian concept of "sovereign" and the possibility of translating it with the words "prince" and "ruler" is discussed.

Related Topics scientific works on philosophy, ethics, religious studies, author of scientific work - Alexander Marey

-

On the Royal Authority to the King of Cyprus, or On the Rule of Princes

2016 / Thomas Aquinas, Alexander Marey -

About Princes and Sovereigns

2018 / Marey A.V. - 2015 / Sergey Kondratenko

-

“Ioannis magister parisiensis doctissimus et eloquentissimus est. . . ". John of Paris and His Time: Politics, Philosophy and Culture in Medieval France

2014 / Alexander Gladkov -

Artistic embodiment of the categories of justice, power and freedom in the works of Ambrogio Lorenzetti

2007 / Romanchuk A.V. -

Discussions about active intelligence at the beginning of the 14th century. and the Basel Compendium

2015 / Khorkov Mikhail Lvovich -

Morality as knowledge in the ethical theory of Thomas Aquinas

2014 / Dushin Oleg Ernestovich -

Can demons work miracles? (question six of Francisco de Vitoria's Lectures on the Magical Art)

2017 / Porfiryeva Sofia Igorevna -

"Does bliss lie in an active intellect?" Compendium of the teachings on the active intellect of the beginning of the 14th century. (ms. UB Basel, cod. B III 22, ff. 182ra-183vb)

2015 / -

"treatise on the soul" by Kassian Sakovich: at the intersection of philosophical traditions

2018 / Puminova Natalia

This article is an introduction to the Russian translation of the first book of Thomas Aquinas ’ treatise “De regimine principum.” The author considers the place of the text within the framework of the European tradition of the Mirrors of Princes, while describing, in brief, the problems of the authorship and the dating of the treatise. Among the European Mirrors of the Princes, the work of Thomas Aquinas , On Kingship; or, On the Government of Princes, has a special place. Thanks to its author’s reputation, this text became one of the most famous influences in both European Late Medieval Philosophy and Modern Political Philosophy. Additionally, this treatise has become a model for two famous works of the same name, On the Government of Princes, written by Ptolemy of Lucca, and Egidio Colonna. In the discussion of the dating of Aquinas’ book, the author holds the opinion that this work was composed between 1271 and 1273, and was addressed to Hugh III Lusignan, the king of Cyprus. The special place in this article is occupied by a small terminological discussion of the Russian translation of the Latin word “princeps.” The author affirms that the existing translation of this word as “Lord” (gosudar) is impossible and quite incorrect. In the author's opinion, the correct translation is “the ruler,” or “the Prince.”

The text of the scientific work on the topic "Thomas Aquinas and the European tradition of treatises on government"

Thomas Aquinas and the European tradition of treatises on government

Alexander Marey

PhD in Law, Associate Professor of the School of Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities, Leading Researcher at the Center for Fundamental Sociology, National Research University Higher School of Economics Address: st. Myasnitskaya, 20, Moscow, the Russian Federation 101000 E-mail: [email protected]

The article is an introduction to the translation into Russian of the first book of the treatise "De regimine principum". It examines the place of the treatise in the tradition of the "rulers' mirror", provides a brief analysis of the problems of authorship and dating of the treatise. Within the framework of the European tradition of mirrors of rulers, the work of Thomas Aquinas "On the Rule of Princes" occupies a special place. Certainly not the first in the tradition, this text has become one of the best known in the genre. According to his model, the treatises of the same name by Ptolemy of Lucca and Aegidius of Rome were written. In the discussion about dating, the author is of the opinion that the treatise was written in 1271-1273, and the King of Cyprus Hugo III Lusignan was its addressee. A separate place in the article is devoted to a discussion about the principles of translation, centered around approaches to the translation of the main categories of Aquinas' political philosophy, primarily princeps. An opinion is expressed about the impossibility of translating it with the Russian concept of "sovereign" and the possibility of translating it with the words "prince" and "ruler" is discussed.

Thomas Aquinas and the tradition of treatises "On Government"

In a series of treatises commonly referred to as "mirrors of the rulers"1, a short text by Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)2 "De regimine principum" is of particular importance. Of course, this kind of instruction was an important part of political culture Western Europe, at least since the formation of the so-called "barbarian" kingdoms, and from this point of view, the treatise of Aquinas fits perfectly into the tradition, being its organic part. On the other hand, there are several important points that distinguish this text from previous works of the same genre.

© Marey A.V., 2016

© Center for Fundamental Sociology, 2016 doi: 10.17323/1728-192X-2016-2-87-95

1. On the genre of “mirrors of rulers” and the role of these texts in shaping the political culture of the European Middle Ages, see: Anton, 2006; Bage, 1987; Darricau, 1979; De Benedictis, Pisapia, 1999.

2. Thomas seems to be too famous a figure to describe his biography here. Let me refer to several fundamental works in which one can read a detailed account of his life and work: Finnis, 1998; Stump, 2012; Stetsyura, 2010.

Russian sociological review. 2016.vol. 15 no 2

First, Aquinas not only updated, but radically changed the apparatus by which the usual problems of royal power were analyzed. Unlike previous "mirrors", built, as a rule, on a thorough exegesis of Holy Scripture and the patristic tradition, Thomas built his text, taking as a basis, first of all, the Aristotelian theory of politics. Of course, he was fluent in both the Old and New Testaments, and the material presented in the Bible was fully reflected in his treatise. However, even the usual biblical arguments, considered in the light of Aristotelian logic, already looked different. In this regard, Thomas should be recognized as an innovator and, one might even say, the ancestor of new tradition"mirrors" - "treatises on government". Almost all subsequent authors, among whom we can recall Ptolemy of Lucca, Egidius of Rome, Dante Alighieri, Marsilius of Padua and others, have already used research optics developed by Thomas in their works.

Secondly, the treatise under consideration was written by Aquinas already at a very mature age, towards the end of his life, when the health of the great theologian left much to be desired. Perhaps the consequence of these circumstances was, on the one hand, the size of the treatise - even if it had been completed by Thomas himself, it would hardly have exceeded 40-45 chapters, grouped into 4 books, and on the other hand, the density of the presentation of the material. Concentrating his attention primarily on the problem of tyranny and its difference from the righteous royal rule, Aquinas, in fact, summarized in this small treatise all those observations that he had generously scattered over several of his large writings (“The sum against the pagans”, “The sum of the theology ”, “Comments on the Maxims” first of all). Unlike, for example, the treatise of the same name by Egidius of Rome, in the reflections of Thomas Aquinas there is not a word about how a king should be brought up, how he should dress, what and how much to drink at the table, etc. There are absolutely no everyday recommendations to the ruler, on the contrary, Aquinas is abstract and rather abstract. Rather, this is not an instruction to the king, in the proper sense of the word, but reflections on the essence and form of royal power, written in a seemingly simple, but at the same time very dense language, requiring calm, thoughtful, slow reading.

Perhaps this feature was the reason for the relatively small popularity of the treatise "On the Rule of Princes" in the Middle Ages. For example, the treatise of the same name by Egidius of Rome, mentioned above, despite its enormous size, was much more widely distributed and was translated into several European languages almost immediately after it was written. The Treatise of Thomas was preserved in 10 major manuscripts (Aquinas, 1979: 448) and, unlike his Summae, was rarely quoted by medieval authors. However, the same brevity and theoretical presentation, along with the personality of the author, who had been canonized by that time, pushed this treatise to one of the first places in the early New Age, when it became literally a reference book for anyone who thought about the problems of royal power and tyranny. Finally, it is this feature of Thomas's text that makes this treatise

one of the most interesting and difficult objects for a translator. However, before talking about the translation of the treatise, it is necessary to briefly analyze the issues related to its authorship and the problem of dating. Inextricably linked with the last question is another one, of a smaller scale, but also important - the question of the addressee of the treatise, the very king of Cyprus, at whose request Thomas wrote this text.

Active studies of the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas began in Europe in the late 70s of the XIX century, after the encyclical "Aeterni Patris", in which Pope Leo XIII called for the study of Christian philosophy, and above all the philosophy of Thomas. However, until the treatise "On the Rule of Princes", researchers seriously got only by the 20s of the XX century. The Italian researcher E. Fiori and the Englishman M. Brown (Browne, 1926; Fiori, 1924) were among the first to address the issues of authorship and dating of the treatise. Casting doubt on the fact that Thomas was the author of the entire treatise, they initiated a discussion in which A. O "Rahilly (O" Rahilly, 1929a, 1929b) took part a little later, who expressed the opinion that the text, starting from 4- th chapter of the 2nd book of the treatise was written by a student and secretary of Thomas Aquinas - Ptolemy of Lucca. The same assertion was confirmed - seemingly conclusively - by Martin Grabmann in his monumental work The Works of St. Thomas Aquinas (Grabmann, 1931).

From this time on, the opinion that Aquinas wrote the first book of the treatise and the first 4 chapters of the second book acquired the status of a proven fact and remained so almost without exception until 1979. This year, the German researcher Walter Mohr, in his Notes on the treatise "De regimine", questioned the authorship of Thomas Aquinas and suggested that the author of the treatise was someone else who remained unknown to us (Mohr, 1974). His position, analyzed in detail by J. Blythe in his preface to the translation of "De regimine" (Blythe, 1997: 3-5), today has practically no supporters, with the exception of E. Black (Black, 1992). , in the absence of an exhaustive codicological and paleographic study of all manuscripts of the treatise, this question still remains open.

For my part, recognizing the importance of the arguments of More and Blythe, I join those scholars who unambiguously attribute the first part of the treatise On the Reign of Princes (De regimine, I-II.4) to Thomas Aquinas. The two most striking arguments concerning, firstly, the serious stylistic differences that exist between this treatise and Aquinas' Summaries, and, secondly, changes in the political position of the author (in the Summa Theology, Aquinas speaks in favor of a mixed constitution, then as in "De regimine" unambiguously states the best form of government is monarchy) may be retorted as follows. The stylistic differences can be explained by the difference in genres - if the "Sums" were, in fact, university notes -

Thomas’s lectures, the treatise “On Government” was rather a consultation, an answer to a private question that came from one of the European monarchs. As for ideological differences, as Leopold Genicot rightly noted, this could be the result of the evolution of Thomas's political views throughout his life (Genicot, 1976). However, as mentioned above, the final answer to the questions of both authorship and dating can only be given by a modern critical edition of the monument.

Regarding the dating of the treatise, there are two main versions. Supporters of the first of them date the treatise to 1266, naming the young king of Cyprus Hugo II of Lusignan (1253-1267) as its addressee. The termination of work on the treatise, within the framework of this hypothesis, is associated with the death of the king, which followed at the end of 1267 (Browne, 1926; Grabmann, 1931; O "Rahilly, 1929a; Sredinskaya, 1990; Aquinas, Dyson, 2002).

The second version, which is much closer to me, belongs to the famous German historian, author of the German translation of The Monarchy, Dante Christoph Fluehler. In his book on the medieval reception of Aristotle's "Politics", Flueler draws attention to the fact that in the text of Thomas's treatise in question there are references to almost all books of the "Politics". This, in turn, suggests that Thomas was familiar with the full text of the Politics, translated into Latin by William of Mörbecke only in 1267-1268. Consequently, the dating of the treatise is shifted by several years, to 1271-1273. (Flüeler, 1993: 27-29), the addressee is the next king of Cyprus - Hugo III Lusignan (12671284), and the reason for the termination of work on the treatise is the death of Thomas.

Translation notes. Context

To date, Anglo-Saxon science holds a confident leadership in the number of translations of the treatise in question - I am aware of the existence of six English versions of "De regimine". Since some of them became available to me thanks to the kind help of A. A. Fisun only when preparing this article for publication, in the course of working on my translation, I used three of them prepared by J. B. Phelan, J. Blythe and R. V Dyson (Blythe, 1997; Aquinas and Dyson, 2002; Aquinas and Phelan, 1949). Almost all of them are distinguished by increased attention to the sources used by Aquinas, and at the same time they do not devote enough space and effort to the conceptualization of the basic concepts of Thomas's political philosophy. This is largely due to linguistic proximity - a fairly large number of terms have passed into English from Latin and practically do not require translation.

The same can be said about the existing translations of "De regimine" into French and Spanish. They were used by me sporadically and, unfortunately, turned out to be almost useless - the practice of tracing terminology, in my deep conviction, entails its “disenchantment”, pre-

rotation from terms to ordinary words of everyday language. So they become, of course, clearer, but lose a fair amount of their original meaning. The same, unfortunately, can be said about the translation of the treatise into German prepared by Fr. Schreifogl (Aquin and Schreyvogl, 1975). It is distinguished by the translator's rather weak attention to the terminology of the translation. This is especially evident when Shreifogl refers to such multi-layered concepts as, for example, "royal service" (officium regis), etc.

Finally, in preparing my translation, I constantly consulted the only existing translation of the treatise "On the Rule of Princes" into Russian. This translation was carried out by N. B. Sredinskaya and partially published in 1990 in a reader on the history of feudal society (Sredinskaya, 1990). During publication, it was severely mutilated - almost all fragments with theological content were cut out of it, and only the reception of Aristotelian thought was left. At the same time, it is obvious that Aquinas was primarily a theologian, and his political theory is also primarily a theological theory. Without taking this into account, including when translating some of the key terms of the treatise, one can lose its entire meaning. To my regret, the complete manuscript of N.B. Sredinskaya today remained inaccessible to me, and its author, in a personal conversation, expressed her fear that it was completely lost. In some cases, I found it possible to follow the translation of Sredinskaya, in others, specially stipulated, I disagreed with her. All cases of my discrepancy in the interpretation of certain concepts with other translations of the treatise are indicated everywhere in the footnotes to the translation.

Translation notes. Terminology

A few words about the principles that guided me when translating Thomas' treatise into Russian. The main difficulty for me was the poorly developed dictionary of Russian political philosophy, which is why the translation of many terms in the text should be considered purely conventional and subject to further discussion and correction.

The thematic specificity of the treatise led to a large proportion of the terminology associated with management. A special place, as can be seen even from the title, is occupied by the figure of princeps "a. In the Russian translation of N. B. Sredinskaya, princeps, in full accordance with Russian tradition, turns into a sovereign, which seems completely unacceptable to me.

In short, my arguments against such a translation can be summarized in three points. First, princeps denotes a relationship of primacy (the word used in Rome for the first senator), while the sovereign marks a relationship of domination. Strictly speaking, etymologically and semantically, the word sovereign can only be translated from the Latin dominus. Secondly, where there is a sovereign, the presence of the state in the sense of this word is implied,

characteristic of the European Modern Age, while there is no connection between the princeps "th and the state as a whole. Thomas Aquinas, as you know, lived in a stateless era - one can argue whether the state existed, say, in Rome, but not with the fact that feudalism as type of social relations is absolutely opposite to any statehood.Where there is feudalism, that is, where legal and political pluralism reigns, where there is no single power, a single legal space, there is no state and cannot be. absolute, complete and indivisible power. The phrase "limited sovereign" causes at best a smile, at worst, simply misunderstanding. Aquinas, however, the very idea of \u200b\u200blimited, absolute power in relation to any secular ruler was alien.

Princeps requires a different translation. Based on the fact that Thomas relied, on the one hand, on the Roman tradition, ascending through Augustine to Cicero, and on the other hand, on the theological tradition, going through the same Augustine to the Holy Scriptures, I believe that it is necessary to look for an adequate translation for the concept of princeps in line with these traditions. This largely explains what I propose as the main equivalent for this concept to use Russian word prince, meaning by this not a specific ruler, but, as generally as possible, a person with power and access to control. This word has serious roots in our political history, but it is also actively used in line with the biblical tradition, to translate the Greek concepts archontes and basileus (I note that the word sovereign is reserved there for the Greek concept kurios, the Latin equivalent of which is just dominus). The second version of the translation of the Latin princeps I see a simple ruler. To take it as the main one prevents me from the fact that the same word - the ruler - in my translation is transmitted the Latin rector, and the ruling word with the same root to it - the Latin regens and presidens.

The rest of the political vocabulary used by Thomas in the treatise raises practically no questions. So, the words "pilot" and "steward", depending on the context, convey the Latin concept of governor; the words "king" or "king" - rex. The word power is used to translate potestas, and sometimes dominium. However, the latter, as a rule, is translated by the concept of dominion, as well as dominatio, which has the same root. The Latin regnum, as long as possible, is transmitted either as a kingdom, or as a royal or royal power. Regimen, in turn, is translated as rule, as well as principatus; if these two terms go as homogeneous (as, for example, at the beginning of the 4th chapter of the treatise), the first is translated as rule, the second as domination.

I will devote a separate study to the analysis of the vocabulary used by Aquinas to describe social reality, which will be published in the next issue of the journal. Therefore, here I will limit myself to a short list of words with their translation options that occur in the treatise. The key concept for social fi-

The philosophy of Thomas is a multitudo, which I, at least for the time being, translate as a totality. The word communion in the text conveys the Latin communitas, and the word communion - societas. Here it is necessary to make a reservation that for Thomas the concept of societas is not a certain subject or object of social relations, not a certain set of people, but the very process of their unity, communication, communication, which determines the choice of a word for translation. The concept of the people is traditionally transmitted by the Latin populus, the word city - civitas.

Quotations from the Holy Scriptures in translation are given according to the Synodal text of the Bible, with the exception of a few fragments, separately specified in footnotes, when Thomas voluntarily or unwittingly distorted the biblical text or when Jerome's translation is especially at odds with modern tradition. "The Sum of Theology" by Aquinas is given in the translation of A. V. Appolonov. Cicero and Sallust are quoted in the translation of V. O. Gorenstein, Titus Livius - in the translation of M. E. Sergeenko. Quotations from Aristotle are based on translations by N. V. Braginskaya (“Nicomachean Ethics”) and S. A. Zhebelev (“Politics”).

Literature

Sredinskaya N. B. (1990). Thomas Aquinas. On the Rule of Sovereigns // Political structures of the era of feudalism in Western Europe (VI-XVII centuries). Leningrad: Science. pp. 217-243.

Stump E. (2012). Aquinas / Per. from English. G. V. Vdovina. M.: Languages of Slavic cultures.

Stetsyura T. D. (2010). Economic ethics of Thomas Aquinas. M.: ROSSPEN. Anton H. H. (2006). Fürstenspiegel des frühen und hohen Mittelalters: Specula princi-pum ineuntis et progredientis medii aevi. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Aquin T. von, Schreyvogl F. (1975). Über die Herrschaft der Fürsten (De regimine princi-

pum). Stuttgart: Reclam. Aquinas Th. (1979). Sancti Thomae de Aquino Opera omnia iussu Leonis XIII P.M. edita.

T. XLII. Roma: Commissio Leonina. Aquinas Th., Dyson R. W. (2002). political writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aquinas Th., Phelan G. B. (1949). De regno ad regem Cypri. Toronto: The Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. Bagge S. (1987). The Political Thought of the King's Mirror. Odense: Odense University Press.

Black A. (1992). Political Thought in Europe, 1250-1450. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blythe J. M. (1997). On the Government of Rulers / De regimine principum; with portions attributed to Thomas Aquinas. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Browne M. (1926). An sit authenticum opusculum S. Thomae "De regimine principum" // Angelicum. Vol. 3. P. 300-303.

Darricau R. (1979). Miroirs des princes // Dictionnaire de spiritualité: ascétique et mystique, doctrine et histoire. Vol. IV. Paris: Beauchesne. P. 1025-1632.

De Benedictis A., Pisapia A. (eds.). (1999). Specula principle. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Finnis J. (1998). Aquinas: Moral, Political and Legal Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fiori E. (1924). Il trattato De regimine principum e le dottrine politiche di S. Tommaso d "Aquino // La Scuola Cattolica. Ser. 7. P. 134-169.

Flueler C. (1993). Rezeption und Interpretation der Aristotelischen Politica im späten Mittelalter. Bohum: B. R. Grüner.

Genicot L. (1976). Le De regno: Speculation ou realisme? // Verbeke G., Verhelst D. (eds.). Aquinas and Problems of His Time. Louvain: Leuven University Press. P. 3-17.

Grabmann M. (1931). Die Werke des Hl. Thomas von Aquin. Münster: Aschendorff.

Mohr W (1974). Bemerkungen zur Verfasserschaft von De regimine principum // Möller J., Kohlenberger H. (eds.). Virtus politics. Stuttgart: Fromann. S. 127-145.

O "Rahilly A. (1929a). Notes on St Thomas. IV: De regimine principum // Irish Ecclesiastical Record. Vol. 31. P. 396-410.

O "Rahilly A. (1929b). Notes on St Thomas. V: Tholomeo of Lucca, Continuator of the De regimine principum // Irish Ecclesiastical Record. Vol. 31. P. 606-614.

Thomas Aquinas and the European Tradition of Treatises on the Government

Alexander V. Marey

Associate Professor, Faculty of Humanities, Leading Researcher, Center for Fundamental Sociology, National Research University Higher School of Economics Address: Myasnitskaya str. 20, 101000 Moscow, Russian Federation E-mail: [email protected]

This article is an introduction to the Russian translation of the first book of Thomas Aquinas" treatise "De regimine principum." The author considers the place of the text within the framework of the European tradition of the Mirrors of Princes, while describing, in brief , the problems of the authorship and the dating of the treatise. Among the European Mirrors of the Princes, the work of Thomas Aquinas, On Kingship; or, On the Government of Princes, has a special place. Thanks to its author"s reputation , this text became one of the most famous influences in both European Late Medieval Philosophy and Modern Political Philosophy. Additionally, this treatise has become a model for two famous works of the same name, On the Government of Princes, written by Ptolemy of Lucca, and Egidio Colonna. In the discussion of the dating of Aquinas" book, the author holds the opinion that this work was composed between 1271 and 1273, and was addressed to Hugh III

Lusignan, the king of Cyprus. The special place in this article is occupied by a small terminological discussion of the Russian translation of the Latin word "princeps." The author affirms that the existing translation of this word as "Lord" (gosudar) is impossible and quite incorrect. In the author's opinion, the correct translation is "the ruler," or "the Prince."

Keywords: Aquinas, De regimine, authorship, dating, Lord, Prince, ruler References

Anton H. H. (2006) Fürstenspiegel des frühen und hohen Mittelalters: Speculaprincipum ineuntis et

progredientismmediiaevi, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Aquin T. von, Schreyvogl F. (1975) Über die Herrschaft der Fürsten (De regimine principum), Stuttgart: Reclam.

Aquinas Th. (1979) Sancti Thomae de Aquino Opera omnia iussu Leonis XIII P.M. edita. T. XLII, Roma: Commissio Leonina.

Aquinas Th., Dyson R. W. (2002) Political Writings, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Aquinas Th., Phelan G. B. (1949) De regno ad regem Cypri, Toronto: The Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Bagge S. (1987) The Political Thought of the King's Mirror, Odense: Odense University Press. Black A. (1992) Political Thought in Europe, 1250-1450, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Blythe JM (1997) On the Government of Rulers / De regimine principum; with portions attributed to

Thomas Aquinas, Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press. Browne M. (1926) An sit authenticum opusculum S. Thomae "De regimine principum". Angelicum, vol. 3, pp. 300-303.

Darricau R. (1979) Miroirs des princes. Dictionnaire de spiritualité: ascétique et mystique, doctrine et

histoire. Vol. IV, Paris: Beauchesne, pp. 1025-1632. De Benedictis A., Pisapia A. (eds.) (1999) Specula principum, Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Finnis J. (1998) Aquinas: Moral, Political and Legal Theory, New York: Oxford University Press. Fiori E. (1924) Il trattato De regimine principum e le dottrine politiche di S. Tommaso d "Aquino. La

Scuola Cattolica, ser. 7, pp. 134-169. Flueler C. (1993) Rezeption und Interpretation der Aristotelischen Politica im späten Mittelalter, Bohum: B. R. Grüner.

Genicot L. (1976) Le De regno: Speculation ou realisme? Aquinas and Problems of His Time (eds.

G. Verbeke, D. Verhelst), Louvain: Leuven University Press, pp. 3-17. Grabmann M. (1931) Die Werke des Hl. Thomas von Aquin, Münster: Aschendorff. Mohr W. (1974) Bemerkungen zur Verfasserschaft von De regimine principum. Virtus politica (eds.

J. Möller, H. Kohlenberger), Stuttgart: Fromann, S. 127-145. O "Rahilly A. (1929) Notes on St Thomas. IV: De regimine principum. Irish Ecclesiastical Record, vol. 31,

O "Rahilly A. (1929) Notes on St Thomas. V: Tholomeo of Lucca, Continuator of the De regimine

principles. Irish Ecclesiastical Record, vol. 31, pp. 606-614. Sredinskaya N. (1990) Foma Akvinskij. O pravlenii gosudarej. Politicheskie struktury jepohi feodalizma vZapadnoj Evrope (VI-XVII vv.), Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 217-243. Stump E. (2012) Akvinat, Moscow: Jazyki slavjanskih kul "tur.

Stetsura T. (2010) Hozjajstvennajajetika FomyAkvinskogo, Moscow: ROSSPEN.

From the standpoint of Christian theology, the original philosophical and legal concept was developed by Thomas Aquinas (1226-1274), the most important authority in medieval Catholic theology and scholasticism, whose name is associated with an influential ideological trend to date - Thomism(in an updated form - neo-Thomism).

His philosophical and legal views are set forth in the treatises "The Sum of Theology", "On the Rule of Sovereigns", as well as in the comments to "Politics" and "Ethics" of Aristotle 1 .

The issue of law and law is interpreted by Thomas Aquinas in the context of Christian ideas about the place and purpose of man in the divine world order, about the nature and meaning of human actions. In covering these issues, he constantly appeals to the theologically modified provisions of ancient authors about natural law and justice, Aristotle's teachings about politics and about man as a "political being" (Thomas also refers to man as a "social being"), etc.

According to Thomas Aquinas, "Man is related to God as from some of its purpose "(The sum of theology, I, q. I, p. 1). At the same time, God, according to Thomas, is the root cause of everything, including human existence and human actions.

At the same time, man is a rational being and has free will, and reason (intellectual abilities) is the root of all freedom.

According to the concept of Thomas, free will is good will. He considers the freedom of the human will and action according to free will to be a manifestation of the due directness of the will in relation to divine goals, the implementation of rationality, justice and goodness in earthly life, the observance of the divine law in its primary sources, which determines the necessary order of the universe.

1 See more: Rare I.G. Encyclopedia of legal and political sciences. SPb., 1872/1873. pp. 809-858; History of political and legal doctrines. Middle Ages and Renaissance. M., 1986. S. 27-39; Borgosh Yu. Thomas Aquinas. M., 1975; Anthology of world philosophy. M, 1969. T. 1. Part 2. S. 823-862; Das Naturrecht in der politischen Theorie. Vienna, 1963.

and human hostel. In the light of such a theological concept of the relationship between freedom and necessity, developed by Thomas 1, - a relationship mediated by the mind that cognizes and determines the practical behavior of people, -: freedom appears as an action in accordance with a reasonably cognized necessity arising from the divine status, nature and goals of the order of the universe and the laws caused by this (goal-conditioned, goal-directed and goal-realizing rules).

Thomas specifies these provisions in his doctrine of law and law."Law," he writes, "is a certain rule and measure of actions by which someone is impelled to action or refrains from it" (Summa teologii, I, q. 90). He sees the essence of law in the ordering of human life and activity from the point of view of bliss as the ultimate goal. Specifying your characterization law as general rule, Thomas emphasizes that the law must express common good all members of society and should be established the whole society(or directly by the society itself or by those to whom it entrusted the care of itself). In addition, the essential characteristic of Thomas's law includes the need for its disclosure, without which its very operation as a general rule and measure of human behavior is impossible.

Thomas summarizes his characteristics of the law in the following definition: "The law is a certain institution of reason for the common good, promulgated by those who have care for society" (Summa teologii, I, q. 90).

Thomas gives the following classification of laws: 1) eternal law (lex aeterna), 2) natural law (lex naturalis), 3) human law (lex humana), and 4) divine law (lex divina).

eternal law represents the universal law of the world order, expressing the divine mind as the supreme global guiding principle, the absolute rule and principle that governs the universal connection of phenomena in the universe (including natural and social processes) and ensures their purposeful development.

The eternal law, as a universal law, is the source of all other laws of a more particular nature. The direct manifestation of this law is natural Law, according to which all divinely created nature and natural beings (including man), by virtue of their innate properties, move towards the realization of goals predetermined and conditioned by the rules (i.e., law) of their nature.

In the future, the idea of the relationship between freedom and necessity from anti-theological positions was developed by a number of thinkers, including Spinoza and Hegel.

The meaning of the natural law for man as a special being endowed by God with soul and mind (the innate, natural light of understanding and cognition) is that man, by his very nature, is endowed with the ability to distinguish between good and evil, is involved in good and is prone to actions and deeds. free will directed towards the realization of good as a goal. This means that in the sphere of practical human behavior (in the field of practical reason, which requires doing good and avoiding evil), there are rules and decrees that naturally determine the order of human relationships due to innate human drives, instincts and inclinations. (to self-preservation, marriage and childbearing, to a hostel, knowledge of God etc.). For man as a rational natural being, to act according to natural law means at the same time the requirement to act at the behest and direction of the human mind.

The difference in the natural (physical, emotional and intellectual) properties and qualities of different people, the variety of life circumstances, etc. lead to unequal understanding and application of the requirements of natural law and a different attitude towards them. The resulting uncertainty associated with vagueness the dictates of natural law, contradicts their obligatory and essentially the same character and meaning for all people. Hence, i.e., from the essence of natural law itself, follows the necessity of human law, which, taking into account the need for certainty and discipline in human relations to the rules and principles of natural law, takes them under protection and concretizes them in relation to various circumstances and particulars of human life.

human law in the interpretation of Thomas - this is a positive law, equipped with compulsory sanction against his violations. Perfect and virtuous people, he notes, can do without human law, natural law is sufficient for them. But in order to neutralize people who are vicious and refractory to convictions and instructions, fear of punishment and coercion are necessary. Thanks to this, innate moral properties and inclinations develop in people, a strong habit is formed to act reasonably, according to free (i.e., good) will.

Human (positive) law, according to the teachings of Thomas, are only those human institutions that correspond natural law(to the dictates of the physical and moral nature of man), otherwise these establishments are not the law, but only a distortion of the law and a deviation from it. Connected with this is Thomas's distinction just and unjust human (positive) law.

Chapter 2. The Philosophy of Law of the Middle Ages

The goal of human law is the common good of people, therefore only those institutions are law that, on the one hand, have in mind this common good and proceed from it, and on the other hand, regulate human behavior only in its connection and correlation with common good, which appears in the form necessary (constituting) attribute and qualities of positive law.

From the conformity of human law to natural law also follows the need to establish in a positive law really feasible requirements, the observance of which is feasible for ordinary, imperfect in their majority, people. A positive law should take people as they are (with their shortcomings and weaknesses), without making excessive demands (in the form, for example, of the prohibition of all vices and all evil).

Related to this is similarity (equality) of requirements, presented by a positive law in the interests of the common good to all people (equality of hardships, duties, etc.). The universality of the law thus implies a moment of equality, in this case in the form of applying an equal measure and the same scale of requirements to all.

A positive law, in addition, must be established by the proper authority (within its powers, without exceeding power) and promulgated.

Only the presence of all these properties and characteristics in human institutions makes them a positive law, obligatory for people. Otherwise, we are talking about unjust laws, which, according to Thomas, not being laws proper, are not binding on people.

Thomas distinguishes two kind unfair laws. Unjust laws of the first type (they lack certain mandatory features of the law, for example, instead of the common good, there is a private benefit of the legislator, his excess of his powers, etc.), although they are not obligatory for subjects, but they compliance is not prohibited in the form of general calmness and undesirability to cultivate the habit of not keeping the law.

The second kind of unjust laws are those that are contrary to natural and divine laws. Such laws are not only optional, but not should be respected and be fulfilled.

Under divine law refers to the law (rules of confession) given to people in divine revelation (in the old and new testament). In substantiating the necessity of the divine law, Thomas points out a number of reasons requiring the addition of human institutions with divine ones.

First, the divine law is necessary to indicate the ultimate goals of human existence, the comprehension of which exceeds one's own limited capabilities. Secondly, bo-

Section V. History of Philosophy of Law and Modernity

the natural law is necessary as the highest and unconditional criterion, which should be guided by the inevitable (for imperfect people) disputes and disagreements about what is proper and fair, about numerous human laws, their merits and demerits, ways to correct them, etc. Thirdly, the divine law is needed in order to direct the internal (spiritual) movements, which remain entirely outside the sphere of influence of the human law that regulates only the outward actions of man. This most important principle of positive legal regulation Thomas very consistently substantiates and implements throughout his teaching on law and law. And, fourthly, the divine law is necessary for the eradication of everything evil and sinful, including everything that cannot be prohibited by human law.

Thomas supplements his interpretation of the laws the doctrine of law.

Law (ius) is, according to Thomas, the action of justice (iustitia) in the divine order of human community. Justice is one of the ethical virtues, which refers to a person’s attitude not to himself, but to other people and consists in repaying each of his own, belonging to him. Thomas, following Ulpian, characterizes justice as an unchanging and constant will to give everyone his own. He shares and Aristotle's idea of two types of justice - equalizing and distributing.

IN Accordingly, the right (understood also as righteous and just) is characterized by Thomas as a certain action, equalized in relation to another person by virtue of a certain equation method. In the equation by the nature of things, we are talking about natural law(ius naturae), with the equation according to human will - about civil, positive law (ius civile).

The right established by the human will (or human law), Thomas also calls human right(ius hu-manum). The law, therefore, plays a legal role here and acts as a source of law. But it is important to keep in mind that, according to the teachings of Thomas, the human will (and will) can make right (and right) only that which corresponds (does not contradict) natural law.

Natural law in the interpretation of Thomas, as in Ulpian, is common to all living beings (animals and people). The natural law that applies only to people, Thomas considers law of peoples(ius gentium).

In addition, Thomas highlights divine right(ius divinum), which, in turn, is divided into natural divine right (immediate deductions from natural law) and positive divine right (for example, the right given by God to the Jewish people).

Chapter 2. The Philosophy of Law of the Middle Ages

In general, Thomas Aquinas developed a very consistent and profound Christian-theological variant of legal

legal understanding. His philosophical and legal views were further developed in the Thomistic and neo-Thomistic concepts of natural law.

2. Medieval lawyers

A significant milestone in the history of philosophical and legal ideas is associated with the work of medieval lawyers.

In general theoretical terms, the legal understanding of medieval jurists in one way or another revolved around the provisions of Roman law and the ideas of Roman jurists as their epicenter and starting point for different kind interpretations and commentaries 1 .

In a number of law schools of that time (X-XI centuries), which arose in Rome, Pavia, Ravenna and other cities, in the course of studying the sources of current law, considerable attention was paid to the relationship between Roman and local (Gothic, Lombard, etc.) law , interpretation of the role of Roman law to fill in the gaps in local customs and codifications.

Under these conditions, the norms, principles and provisions of Roman law in their meaning go beyond the sphere where they directly play the role of an acting source of law, and begin to acquire a more general and universal meaning. A significant place in the then legal understanding begins to be again given to the idea of justice (aequitas) developed in Roman jurisprudence and accepted in the system of Roman law and related natural law ideas and approaches to the current, positive law.

I.A. Pokrovsky noted that "in the jurisprudence of the Pavia school, the conviction early formed that in order to replenish the Lombard law, one should turn to Roman law, that Roman law is common law lex generalis omnium. On the other hand, the novelists of Ravenna took Lombard law into account. In the same cases where legal systems collided with each other and

1 Noting the positive aspects of such an orientation of medieval legal thought and various legal schools and trends towards Roman law, the pre-revolutionary Russian historian of law A. Stoyanov wrote: “War and scholastic dreams absorbed the activities of the majority in medieval society. Brute force and lofty, stillborn philosophies were the dominant phenomena. Meanwhile, the human mind needed healthy food, positive knowledge. that Roman law was the most practical and healthy product of human thought at a time when the European peoples began to feel a thirst for knowledge in themselves ... The scientists of the school of Roman law, as an organ of legal propaganda, were necessary under such conditions. - Stoyanov A. Methods for the development of positive law and the social significance of lawyers from the glossators to the end of the 18th century. Kharkov, 1862. S. 250-251.

444 Section V. History of Philosophy of Law and Modernity

contradicted each other, jurisprudence considered itself entitled to choose between them for reasons of justice, aequitas, as a result of which this aequitas was elevated by them to the supreme criterion of all law. Hence the further view that even within each individual legal system, every norm is subject to evaluation from the point of view of the same aequitas, that a norm that is unjust in application can be rejected and replaced by a rule dictated by justice ... The concept of aequitas is thus identified with the concept of ius naturale and thus the jurisprudence of this time, in its general and basic direction, is the forerunner of natural law school later era" 1 .

This direction was later replaced (end of the 11th - mid-13th centuries) by the school of glossators (or exegetes), whose representatives began to focus on the interpretation (i.e., exegesis, glossator activity) of the very text of the sources of Roman law - the Code of Justinian and especially Digest. This turn from the assessment of certain norms in terms of aequitas to the study of Roman law as a source of positive law is associated primarily with the activities of the lawyers of the University of Bologna, which arose at the end of the 11th century. and soon became the center of the then legal thought.

A similar approach to law was developed in other universities (in Padua, Pisa, Paris, Orleans).

Famous representatives of the school of glossators were Irne-riy, Bulgar, Rogerius, Albericus, Bassianus, Pillius, Vakari-us, Odofredus, Atso. The main glosses - the result of the activities of the entire direction - were collected and published by Accursius in the middle of the 13th century. (Glossa Ordinaria). This collection of glosses enjoyed high prestige and played in the courts the role of a source of current law.

The glossators made a significant contribution to the development of positive law, to the formation and development of legal-dogmatic method interpretation of the current legislation. “First of all,” wrote A. Stoyanov about the activities of the glossators, “they explain to themselves the meaning of individual laws. Hence the so-called legal exegesis (exegesa leqalis), the first step, the ABC of the science of positive law. But from the explanation of individual laws, the higher, theoretical requirements of the mind led jurists to a logically coherent presentation of entire doctrines within the same legal limits of sources. This is a dogmatic element. In addition, the legal literature of the early thirteenth century represents an attempt to expound the teachings of Roman law on its own, without adhering to the order of titles and books of the Code. Here is the germ of a systematic element. Thus glossators attacked those living parties that should be in

1 Pokrovsky I.A. History of Roman law. Petrograd, 1918. S. 191-192.

Chapter 2. The Philosophy of Law of the Middle Ages

method of jurisprudence as a science in the true sense of the word. The study of positive law cannot be dispensed with without exegesis, without dogmatic and systematic treatment. Here are expressed the basic, unchanging methods of the human mind, which are called analysis and synthesis" 1 .

The problem of the relationship between law and law, justice (aequi-tas) and positive law, in the presence of contradictions between them, was decided by the glossators in favor of official legislation, and in this sense they were lawyers, standing at the origins of European medieval legalism. In this regard, I.A. Pokrovsky rightly noted: “... In contrast to the former freedom of dealing with positive law and the freedom of judicial discretion, the Bologna school demanded that the judge, abandoning his subjective ideas of justice, adhere to the positive norms of the law, i.e. Corpus uris Civilis. Already Irnerius declared that in the event of a conflict between the ius and the aequitas, the decision belongs to the legislature" 2 .

Postglossators (or commentators), occupied a dominant position in jurisprudence in the XIII-XV centuries, the main attention began to be paid to commenting on the glosses themselves. Representatives of the school of post-glossators (Ravanis, Lull, Bartholus, Baldus, etc.), relying on the ideas of scholastic philosophy, sought to give a logical development of such a system of general legal principles, categories and concepts, from which more particular legal provisions, norms and concepts can be deduced in a deductive way.

Unlike glossators, post-glossators again refer to ideas of natural law and the corresponding teachings of the Roman jurists and their other predecessors. At the same time, they interpret natural law as an eternal, reasonable law, derived from the nature of things, compliance with which acts as a criterion for recognizing certain norms of positive law (norms of legislation and customary law).

A number of the main provisions of this school were formulated by its prominent representative Raymond Lull(1234-1315).

Jurisprudence in the interpretation of Lull and other glossators is permeated with ideas and ideas of scholastic philosophy and theology. But Lully "has also other, for him secondary, but in essence more scientific aspirations, namely: 1) to give jurisprudence a compendial exposition and to derive from the universal principles the rights of the beginning, special, by artificial means; 2) in this way to impart to the knowledge of law the property of science; 3) to reinforce the meaning and strength of written law, harmonizing it with natural law, and to refine the mind of a lawyer" 3 .

Stoyanov A. Decree. op. pp. 4-5. " Pokrovsky I.A. Decree. op. P. 194. Stoyanov BUT. Decree. op. P. 10.

Nersesyants "Philosophy of Law"

Section V. History of Philosophy of Law and Modernity

Outlining the techniques of his new approach to law and his understanding "legal art" Lull puts forward, in particular, the following requirements: "reducere ius naturale ad syllogysmum" ("reduce natural law into a syllogism"); "ius positivum ad ius naturale reducatur et cum ipso concordet" ("the positive right to reduce to natural law and harmonize with it") 1 .

Correlation between law and law is decided by Lull in such a way that the recognition of the primacy of natural law over positive law is combined with the search for agreement and correspondence between them. Even rejecting this or that unjust provision of positive law, which contradicts natural law, one should, according to Lulliya, avoid their critical opposition. “A lawyer,” he wrote, “is obliged to investigate whether the written law is fair or false. If he finds it fair, then he must draw correct conclusions from it. If he finds it false, then he must not only use it, without condemning it and about him, so as not to bring disgrace on the elders "(i.e. legislators) 2 .

In addition to the moment of substantive correspondence of the norms of positive law to the meaning and essence of natural justice and reasonable necessity, Lull, in the spirit of scrupulous scholastic logic, also outlines a formalized way of checking the compliance or non-compliance of positive law (secular and canonical) with natural law. “This method,” he notes, “is this: first of all, the lawyer must divide the secular or spiritual law on the basis of a paragraph on the difference ... After separation, agree on its parts one with the other on the basis of a paragraph of agreement ... And if these parts, having united, make up a complete law, hence it follows that the law is just... If the law, spiritual or secular, does not stand up to this, then it is false and there is nothing to care about it "3.

Legal content the characterization of positive legislation from the standpoint of natural law is thus combined and supplemented in Lull's approach with the requirement formalistic procedures for checking the internal integrity, consistency and consistency of the law as a source of valid law. The injustice of a law contrary to natural law, understood by Lull as at the same time its falsity and unreasonableness (divergence from the necessities arising from reason), also meant its self-contradiction, its inconsistency also in the formal-logical plan. This idea underlies the logical procedure proposed by Lull for checking the legal value of a law.

1 Ibid. S. 11.

2 See ibid.

3 See ibid.

Chapter 2. The Philosophy of Law of the Middle Ages

Similar ideas about the nature of the relationship between natural and positive law were developed by Baldus, who argued that natural law is stronger than the principate, the power of the sovereign ("po-tius est ius naturale quam principatus") 1 .

The legal provisions developed and substantiated by lawyers of the post-glossary school have received wide recognition not only in theoretical jurisprudence, but also in legal practice, in judicial activity. The comments of a number of prominent post-glossators were for the then judges the significance of a source of effective law, so that without any exaggeration one can speak of their law-making role 2 .

From the beginning of the XVI century. in jurisprudence, the influence of the post-glossator school is noticeably weakening. At this time, the so-called humanistic school(humanistic direction in jurisprudence). Representatives of this direction (Budaus, Alziatus, Tsaziy, Kuyatsiy, Donell, Douarin, etc.) again focus on a thorough study of the sources of current law, especially Roman law, an intensified process reception which required the harmonization of its provisions with the historically new conditions of socio-political life and with the norms of local national law. Techniques begin to take shape and apply philological and historical approaches to the sources of Roman law, the rudiments of historical understanding and interpretation of law are developing.

For lawyers of the humanistic school, law is, first of all, positive law, legislation. Lawyers XVI in. are predominantly legalists, opposed to feudal fragmentation, for the centralization of state power, unified secular legislation, and the codification of existing positive law. Such legalism, along with the protection of the absolute power of kings, included in the works of a number of lawyers and idea of legality and legalism in a broader sense (the idea of universal freedom, equality of all before the law, criticism of serfdom as an anti-legal phenomenon, etc.). Characteristic in this regard, in particular, is the anti-serf position of the famous French lawyer Beaumanoir, asserting that "every person is free" 3 and striving to implement this idea in their legal provisions and constructions.

At the same time, the focus of the attention of lawyers of the named direction on positive law was not accompanied by a complete denial of natural law ideas and ideas. It's obvious already

1 See: Pokrovsky I.A. Decree. op. S. 198.

2 Thus, the comments of Bartholus (1314-1357) "enjoyed extraordinary authority in the courts; in Spain and Portugal they were translated and even considered binding on the courts." - Pokrovsky I.A. Decree. op. S. .199.

3 See: Stoyanov BUT. Decree. op. S. 35.

448 Section V. History of Philosophy of Law and Modernity

from the fact that the existing positive law also included Roman law, which included these ideas and ideas. It is significant that a number of lawyers of that time (for example, Donell), characterizing the place and role of Roman law among the sources of existing law, regarded it as "the best objective norm of natural justice" 1 .

The concepts of legal understanding of medieval jurists (of a legal and legal nature and profile) significantly deepened the development of the problems of distinguishing between law and law, and later - as an important theoretical source - played a significant role in the formation of the philosophy of law and legal science of modern times.

Grotius

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) - one of the early creators of the "legal worldview" of modern times. He made a huge contribution to the formation of the modern doctrine of international law, to the formation of the foundations new rationalistic philosophy of law and state.

All social issues (domestic and international profile) are studied by Grotius from the standpoint of natural law, through the prism of ideas and requirements of legal justice, which should prevail in relations between individuals, peoples and states.

Also, the theme of war and peace - the subject of special studies of Grotius - turns out to be a legal problem in his interpretation, which he expresses in a concentrated form as the right of war and peace.