1613 election of Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov to the kingdom. Election of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov to the kingdom

The end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries became a period of socio-political, economic and dynastic crisis in Russian history, which was called the Time of Troubles. The Time of Troubles began with the catastrophic famine of 1601-1603. A sharp deterioration in the situation of all segments of the population led to mass unrest under the slogan of overthrowing Tsar Boris Godunov and transferring the throne to the “legitimate” sovereign, as well as to the emergence of impostors False Dmitry I and False Dmitry II as a result of the dynastic crisis.

"Seven Boyars" - the government formed in Moscow after the overthrow of Tsar Vasily Shuisky in July 1610, concluded an agreement on the election of the Polish prince Vladislav to the Russian throne and in September 1610 allowed the Polish army into the capital.

Since 1611, patriotic sentiments began to grow in Russia. The First Militia, formed against the Poles, never managed to drive the foreigners out of Moscow. And a new impostor, False Dmitry III, appeared in Pskov. In the fall of 1611, on the initiative of Kuzma Minin, the formation of the Second Militia began in Nizhny Novgorod, led by Prince Dmitry Pozharsky. In August 1612, it approached Moscow and liberated it in the fall. The leadership of the Zemsky militia began preparing for the electoral Zemsky Sobor.

At the beginning of 1613, elected officials from “the whole earth” began to gather in Moscow. This was the first indisputably all-class Zemsky Sobor with the participation of townspeople and even rural representatives. The number of “council people” gathered in Moscow exceeded 800 people, representing at least 58 cities.

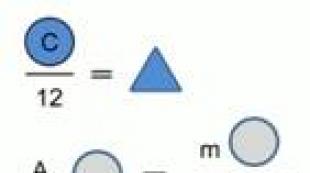

The Zemsky Sobor began its work on January 16 (January 6, old style) 1613. Representatives of “the whole earth” annulled the decision of the previous council on the election of Prince Vladislav to the Russian throne and decided: “Foreign princes and Tatar princes should not be invited to the Russian throne.”

The conciliar meetings took place in an atmosphere of fierce rivalry between various political groups that took shape in Russian society during the Time of Troubles and sought to strengthen their position by electing their contender to the royal throne. The council participants nominated more than ten candidates for the throne. Various sources name Fyodor Mstislavsky, Ivan Vorotynsky, Fyodor Sheremetev, Dmitry Trubetskoy, Dmitry Mamstrukovich and Ivan Borisovich Cherkassky, Ivan Golitsyn, Ivan Nikitich and Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov, Pyotr Pronsky and Dmitry Pozharsky among the candidates.

Data from the “Report on Patrimonies and Estates of 1613,” which records land grants made immediately after the election of the Tsar, make it possible to identify the most active members of the “Romanov” circle. The candidacy of Mikhail Fedorovich in 1613 was supported not by the influential clan of Romanov boyars, but by a circle that spontaneously formed during the work of the Zemsky Sobor, composed of minor figures from the previously defeated boyar groups.

According to a number of historians, the decisive role in the election of Mikhail Romanov to the kingdom was played by the Cossacks, who during this period became an influential social force. A movement arose among service people and Cossacks, the center of which was the Moscow courtyard of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, and its active inspirer was the cellarer of this monastery, Abraham Palitsyn, a very influential person among both the militias and Muscovites. At meetings with the participation of cellarer Abraham, it was decided to proclaim 16-year-old Mikhail Fedorovich, the son of Rostov Metropolitan Philaret captured by the Poles, as tsar.

The main argument of Mikhail Romanov’s supporters was that, unlike elected tsars, he was elected not by people, but by God, since he comes from a noble royal root. Not kinship with Rurik, but closeness and kinship with the dynasty of Ivan IV gave the right to occupy his throne.

Many boyars joined the Romanov party, and he was also supported by the highest Orthodox clergy - the Consecrated Cathedral.

The election took place on February 17 (February 7, old style) 1613, but the official announcement was postponed until March 3 (February 21, old style), so that during this time it would become clear how the people would accept the new king.

Letters were sent to the cities and districts of the country with the news of the election of a king and the oath of allegiance to the new dynasty.

On March 23 (13, according to other sources, March 14, old style), 1613, the ambassadors of the Council arrived in Kostroma. At the Ipatiev Monastery, where Mikhail was with his mother, he was informed of his election to the throne.

Source:

Work of Professor D. V. Tsvetaev,

Manager of the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Justice.

“ELECTION OF Mikhail Feodorovitch Romanov TO THE KINGDOM”

1913 edition

T. SKOROPECHATNI-A.A. LEVENSON

Moscow, Tverskaya, Trekhprudny lane, coll. D.

III.

The composition of the electoral zemsky council of 1613.

Having occupied and cleaned the Kremlin, the boyar Prince. Dmitry Timofeevich Trubetskoy and the steward, Prince Dmitry Mikhailovich Pozharsky, who headed the provisional government, began immediately preparing for the speedy convening of a plenipotentiary council. Now, it seemed, the most convenient time had come for the urgent implementation of the idea that was brewing in everyone’s mind:

It’s impossible to be without a sovereign for even a short time, and the Moscow state has had enough of being ruined”; “It is not possible for us to remain without a king for a single hour, but let us choose a king for our kingdom..

The governors acted here in agreement with all the officials of the state who were with them, i.e. with the zemstvo council or cathedral, which was formed from the councils that consisted of the militias; at the head of the consecrated cathedral was, as before, as in Yaroslavl, Metropolitan Kirill of Rostov and Yaroslavl. If previously both leaders could only convene with those cities that were adjacent to each of them separately, now the practice of convening has changed. It was decided to “exile to all cities with all sorts of people, from small to large,” in order to “turn on the Vladimir and Moscow states and all the great states of the Russian kingdom of the Tsar and the Grand Duke, God willing.”

And so, through the messengers, letters of convocation rushed, as the official narrative puts it, “to the Moscow state, to the Ponizovye, and to the Pomeranian, and to the Seversky, and to all the Ukrainian cities.” The certificates were addressed to all ranks: the consecrated cathedral, boyars, nobles, servants, guests, townspeople and district. The highest spiritual authorities were called upon to “arrive in Moscow”, as those who were part of the consecrated cathedral, according to their position; cities were invited, “having given advice and a strong verdict,” to send “for the Zemstvo Great Council and the State’s robbing” “ten of the best and most intelligent and stable people,” or “as appropriate,” choosing them from all ranks: “from nobles, and from the children of boyars, and from guests, and from merchants, and from Posatsky, and from district people "). The city's elected officials had to give a “complete and strong sufficient order” so that on behalf of their city and district they could “speak freely and fearlessly about state affairs,” and warn them that at the council they should be “straightforward without any cunning.”

Elections were to be carried out immediately, “ignoring all other matters.” The date for the congress in Moscow was set at Nikolin's autumn day (December 6). “Otherwise it was written to you at the end of the letters, we give you information, and you yourself know that, only soon we will not have a sovereign in the Moscow state, and it is not at all possible for us to be without a sovereign; and in no states does the state exist anywhere without a sovereign.” The Novgorod Metropolitan, whose letter was to become known to the Swedish government, was diplomatically notified (November 15) that when the council meets in Moscow and he knows about the arrival of the prince Prince Karl-Philipp Karlusovich in Novgorod, then ambassadors will be sent to the latter with a full agreement on state and about zemstvo affairs. There was no mention of the date of the convocation, but instead they reported that “they wrote to Siberia and Astrakhan about fleecing the state and about advice on who should be in the Moscow state.” This mention shows that the leaders here were the same people who were in Yaroslavl: it was not the custom to call representatives of remote and unsettled Siberia, into the depths of which they were gradually moving aggressively, to the council; and there was no way that deputies from such remote places could have arrived at the actual convening date. The warning skillfully made it clear to the Swedes that the council would not begin soon, and thus tried to gain time for them.

The elected officials arrived in Moscow gradually, much behind the deadline indicated in the letters; Due to the difficulty of getting ready and the inconvenience and danger of communication routes, many could not keep up with him. After the first draft letters, the second ones were sent, with the requirement that they not delay in sending the authorized representatives; it was prescribed to equip and not be embarrassed by the number, “as many people as fit.” The first traces of the cathedral's activities were preserved from the following January 1613, when it was still far from being at full strength).

Speaking about the composition of the cathedral, it should be noted that in the 17th century the zemstvo cathedrals included: the consecrated cathedral, the boyar duma and representatives of different classes or social groups and strata, service and taxation. Members of the consecrated cathedral and the boyar duma (due to the position of these two government institutions) were present at the councils in one composition. However, the events of the Troubles could not help but affect many of these members: some were in captivity or captivity, some fell under suspicion. The latter fate befell the most prominent members of the Duma. If the government of the leaders who liberated Moscow came to the council unhindered, then those members of the Duma who allowed the Polish garrison into Moscow and wrote and acted against Trubetskoy and Pozharsky had different prospects. Those less noble and more compromised by their service to the Poles were imprisoned and punished. “The most noble boyars, as they say about them, left Moscow and went to different places under the pretext that they wanted to go on a pilgrimage, but more for the reason that all the ordinary people of the country were hostile to them because of the Poles with whom they were at the same time, therefore they need to not show themselves for a while, but hide from view.” They even say that they “were declared rebels” and that inquiries were made around the cities as to whether they would be allowed into the Duma. Far-sighted rulers, having arranged an honorable meeting for these noble persons upon leaving the Kremlin and providing protection from the robbery of the Cossacks, tried and then to support them in public opinion, pointing out that they endured all sorts of oppression from the Poles: “they were all in captivity, and some were for bailiffs.” ", Prince Mstislavsky, "Lithuanian people beat the coins, and his head was beaten in many places." No matter how to explain the departure of the prince. F.I. Mstislavsky with his comrades from Moscow, whether due to a personal desire for rest or external motives, there is no doubt that they were not present at the first meetings of the council and were called to it later, in fact, to participate in the solemn proclamation of the already elected sovereign.

However, not all boyars left Moscow. For example, the boyar Feodor Ivanovich Sheremetev remained. He also signed the letters with which the Kremlin Duma boyars exhorted (January 26, 1612) the “Orthodox peasants” to leave “the thieves’ troubles”, not to follow Pozharsky, but “to our Great Sovereign Tsar and Grand Duke Vladislav Zhigimontovich of All Russia for the wine bring your own and cover it with your current service.” His cousin, Ivan Petrovich Sheremetev, a supporter of Vladislav, did not allow the Nizhny Novgorod militia into Kostroma, for which the Kostroma residents removed him from the voivodeship and almost killed him. Saved from death by the prince. Pozharsky, he joined the ranks of the Nizhny Novgorod army; book Pozharsky was so convinced of his trustworthiness that upon leaving Yaroslavl he left him there as commander. Another nephew of Feodor Ivanovich came to Moscow with the Nizhny Novgorod militia. Both were supposed to bring Feodor Ivanovich Sheremetev closer to the prince. Pozharsky. During the siege, he was in charge of the State Household in the Kremlin, a report on the state of which he was now supposed to submit; with his comrades, he then did what he could to preserve the regalia and some other royal treasures, as well as to protect his loved ones, by wife, relatives of the old woman Marfa Ivanovna Romanova with her young son Mikhail (Sheremetev was married to the cousin of Mikhail Fedorovich). Before they had time to send out all the letters calling for the council, he received (November 25, 1612) from Trubetskoy and Pozharsky a large courtyard space in the Kremlin, “to build a courtyard on that place.” Sheremetev thus began construction where the cathedral met and met; he could conveniently keep abreast of the whole matter, and then began to participate in the council itself. When discussing the candidacy of Mikhail Fedorovich, this circumstance could have its significance).

Thus, at the beginning of the electoral council, mainly militia dignitaries led by princes Trubetskoy and Pozharsky sat and acted as members of the Duma, who, of course, opened the cathedral and supervised its proceedings. The boyars, members of the previous government, who, due to their nobility, occupied the leading places in most cases, came to the final, ceremonial meetings. Prince Feodor Ivanovich Mstislavsky signed the approved document on the election of Mikhail Fedorovich to the kingdom as the first of the secular dignitaries), immediately after the non-elected members of the consecrated council (33rd), the boyars princes Ivan Golitsyn, Andr. Sitskaya and Iv. Vorotynsky. The liberating princes occupied only 4 and 10 places in the signatures on one copy of the letter, and even 7 and 31 places on the other. Duma ranks, highest ranks of courtiers and clerks are named on the charter in total up to 84 persons). The rest of the secular non-elected members of the cathedral also belonged to the upper strata of the service class. Among the non-elected members there were quite a few people who had family ties with the Romanovs: in addition to F.I., Sheremetev, the Saltykovs, the princes of Sitsky, the princes of Cherkassy, Prince. Iv, Katyrev-Rostovsky, book. Alexey Lvov and others.

The events of the Time of Troubles brought forward the moral significance of the consecrated cathedral: its Russian members steadily advocated for Orthodox Russian principles. After the martyrdom of Hermogenes, the patriarchal throne remained vacant; Metropolitan of Rostov Filaret and Archbishop of Smolensk Sergius languished with Prince. You. You. Golitsyn, Shein and comrades in Polish captivity, the Novgorod metropolitan was bound by the Swedish authorities. At the head of the consecrated cathedral was its former chairman, Metropolitan Kirill, who held primacy for a long time and was the only metropolitan both in the elective cathedral meetings and during the embassy to Mikhail Fedorovich with an invitation to the kingdom. Metropolitan Ephraim of Kazan, successor of Hermogenes, who was considered one of the voices of the spiritual hierarchy, came to the meeting and coronation; he took first place in the consecrated cathedral and was the first to sign the Approved Charter. Upon his arrival in Moscow, he ordained Gon as metropolitan of Sara and Pond, who then ruled the Russian church until the return of Filaret Nikitich. All three metropolitans signed the Approved Charter). They were followed by three archbishops, including Theodoret of Ryazan, two bishops, archimandrites, abbots, and celari. The abbots of five monasteries were present from the Moscow monasteries, and from the Kremlin Miracle Monastery, where Hermogenes died, there was, in addition to the archimandrite, a cellarer. The Trinity-Sergius Lavra was first represented by both of its famous figures, Archimandrite Dionysius and cellarer Abraham Palitsyn, who later replaced Dionysius and signed the charter alone; Archimandrite Kirill was present from the Kostroma Ipatiev Monastery. The total number of members of the consecrated cathedral according to hierarchical position was 32. Many cities, among their elected representatives, sent clergy, archpriests and priests of local churches and abbots of monasteries.

From the non-elected, official part of the Zemsky Sobor, a total of 171 persons were named in the assault. This number is probably quite close to reality: there is no reason to think that a significant part of the non-elected members did not give their signatures.

87 elected secular members of the cathedral were named in assault. Undoubtedly, there were significantly more of them). Among them, people belonging to the middle strata of the service class and townspeople predominated; there were also palace and black peasants, instrumental people and even representatives of eastern foreigners 2). As for the territorial distribution of the electors, as can be seen from the letter, they came from no less than 46 cities. Zamoskovye, in particular its main, northeastern part, was especially fully represented. This circumstance is easily explained by the size of the Zamoskovye territory, the abundance of cities on it, the immediate participation of cities, namely its northeastern part, in previous measures to restore state order and, finally, by the fact that there was a cathedral within the Zamoskovye region).

The active participation taken in the events by the cities of the Pomeranian region suggests that this region was well represented at the council; The absence of signatures of electors on the conciliar charter, except for one, from the cities of this region must be entirely attributed to the incompleteness with which elective representation was generally reflected in the assault. But from the lands stretching towards Pomerania, representatives of Vyatka are known by name among four.

In second place in terms of the number of names mentioned in assaults is the region of Ukrainian cities, from which Kaluga was sent, by the way, by Smirna-Sudovshchikov, whose activities we will have to meet. Then come the rest of the regions adjacent to Zamoskovye from the south: Zaotsky cities, Ryazan region, as well as the southeast-Niz, with its former Tatar capital Kazan; sent his electors and the far south: the North and the Field, in particular, from another source, we learn about the energetic representative of the “glorious Don”. In an extremely unfavorable position regarding the opportunity to take part in the council at that time, of course, were the cities from the German and Lithuanian Ukraine, which, judging by the assaults, were really the weakest represented; nevertheless, they also participated in the conciliar election of the sovereign).

In general, at the council of 1613, all major groups of the population of the Moscow state were represented by its non-elected and elected participants, except for the privately owned peasantry) and serfs.

In territorial terms, the representation at it appears to us even more complete, if we take into account from which cities the clergy came to the council, who were present here by virtue of their official position, and not by choice: then the above number of cities (46), undoubtedly presented at the council, at least 13 more should be added, not counting the capital. If the cities generally followed the norm regarding the number of electives indicated in the invitation letters, and even if only about 46 cities sent electives, then the number of all members of the council exceeded 600.

Thus, despite the haste with which elections had to be carried out, and the difficulties during the congress of members in the capital, the council of 1613 was complete in its composition. At the same time, it clearly outlines the middle classes of the population, far from the oligarchic or foreign tendencies of the upper layer and from the aspirations of the willful Cossacks; it clearly reflects the broad movement of the zemshchina to protect and restore Russian statehood.

NOTE:

1) In view of the uneven composition of the population in cities, letters (for example, addressed to Beloozero) ordered that a choice be made “from abbots, and from archpriests, and from townspeople, and from district people, and from palace villages, and from black volosts,” “and district peasants” (added another); or they demanded (for example, in Ostashkov) that “ten reasonable and reliable people” be sent “from priests, nobles, townspeople and peasants” living in such and such a city and its district. Acts of Moscow region militias, No. 82, 89; Arsenyev Tver Papers, 19-20.

2) Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles, V, 63; Palace Classes, I, 9-12, 34, 183; Collection of state charters and agreements, I, 612; III, 1-2, 6; Additions to Historical Acts, I, No. 166; Acts of the Moscow Region militias, No. 82. - As for the message from the authorities to the Novgorod Metropolitan about writing “to Siberia,” it should be noted that in the surviving district charter through Perm to the Siberian cities, princes Pozharsky and Trubetskoy only notified these cities about the liberation of Moscow and punished they should sing prayers with ringing bells on the occasion of such a joyful event, but they say nothing about sending delegates to the council and about the council itself (Collection of state charters and agreements, I, no. 205); there is no mention of an invitation from Siberia in the official Palace Discharges (I, 10).

Distribution of letters of summons began earlier on November 15, 1612: Additions to the Historical Acts, I, 294. The letter to Beloozero was sent on November 19, delivered quickly, on December 4; but by the deadline, the Beloozersky residents, who still needed time to conduct elections, could not get to the council. The second letter, received on December 27, ordered the electors to be sent immediately, “not to give them any time.” They could get to Moscow no earlier than the second half or even the end of January (Acts of the Moscow Region militias, 99, 107, and preface, XII; Collection of state charters and agreements, I, 637). Members of the cathedral from more distant points and more dangerous along the way could arrive even later. The first document from the activities of the cathedral was the letter of complaint from Prince. Trubetskoy on Vaga, in January 1613, there are 25 signatures under it. Appendix No. 2 to the work of I. E. Zabelin “Minin and Pozharsky”. M., 1896, 278-283,

4) Approved letter of election to the Moscow state of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov. Publication of the Imperial Society of Russian History and Antiquities, first (1904) and second (1906). Previously published in the Ancient Russian Vivlioik, vol. V of the first edition and vol. VII of the second, and in the Collection of state charters and agreements, vol. I, No. 203. In the absence of a list of members of the council and news of their number, the signatures on it are the most important, albeit very imperfect, source of information about the composition of the cathedral.

This charter was made in two copies." The earlier one apparently (see “Approved Charter,” ed. 2, preface, p. 11) is now kept in the Armory Chamber; the second is in the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In both signatures are separated by blank spaces into 4 departments: 1) the ranks of the consecrated cathedral and the Duma; 3) the rest of the non-elected members; 4) the consistency in the distribution of signatures between departments is not always maintained due to the fact that the holder often signed not only for himself, but also. for other persons, on behalf, the number of persons named in the assaults is greater than the number of assaults: according to our calculation, 238 signatures of the first copy give 256 names; copies - 283, with the support of Duma clerk P. Tretyakov - 284. This figure does not coincide with the calculations of previous researchers (Prof. Platonov, Avaliani, etc.) The document was drawn up two months after the fact; signatures took even longer to collect; in addition, not all participants in the election could give their signatures, and on the other hand, signatures were given by persons who were not at the council during the election period.

5) Namely: 11 boyars, 7 okolnichikhs, 54 highest court ranks, at least 11 clerks, of which 1 was Duma. In this calculation, we mean the title that the signatories wore during the period of the royal election, and not at the time of signing the charter. From okolnichy books. Grigor. Petrov. Romodanovsky and Bor. Mich. Saltykov signed the charter after receiving the boyars, Mich. Mich. Saltykov - after receiving the title of kraychago. Among the highest court ranks who signed the charter there are 1 cup maker, 34 stewards, 19 solicitors. From the book's stolniks. Dm. Mikh, Pozharsky and Prince. Iv. Bor. Cherkassky signed after receiving the noble status. Prince Yves also signed up as a boyar. Andr. Khovansky, and the number of higher court ranks during the Tsar’s election increases with him by another 1. Stepan Milyukov, who signed himself as a solicitor, did not yet hold this title at the time of the Tsar’s election. Some of the attackers signed without indicating their rank; e.g., stolniks of the book. Iv. Katyrev-Rostovsky and Prince. Iv. Buynosov, solicitor Dementy Pogozhev, clerks, except Pyotr Tretyakov and Sydavnoy Vasiliev. At the time of the election of the tsar, only the latter of these two was the Duma clerk. See A v a p i a n i, Zemsky Sobors, part II, pp. 81 and 82.

6) On the charter of the Zemsky Sobor, Prince. Trubetskoy on Vaga in January 1613, Metropolitan Kirill was the first to sign, and there are no other metropolitan signatures on it (3 abelina, No. II, p. 282). The charter of the cathedral, sent to the elected Mikhail Feodorovich in March, begins: “To the Tsar and Grand Duke Mikhail Feodorovich of all Russia, your sovereign pilgrims: Metropolitan Kirill of Rostov, and archbishops, and bishops, and the entire consecrated cathedral, and your slaves: boyars, and okolnichy ...” He was one of the metropolitans indicated both in the correspondence between the cathedral and the ambassadors and in the royal letter notifying him of the day of his arrival in Moscow. Collection of state charters and agreements, III, No. 2-6; Palace Classes, I, 18, 24, 32, 35, 1185, 1191, P95, 1209, 1214, etc. Metropolitan Ephraim was in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra when the sovereign stopped there on his way to Moscow, April 27. Palace Discharges, I, 1199. Jonah was made metropolitan shortly after May 24, 1613. His Eminence Macarius, History of the Russian Church, vol. X, St. Petersburg, 1881, 169.

7) The discrepancy between the number of names and the actual number of members of the cathedral is explained mainly by the substitution practiced when signing the charter: when signing for other elected representatives from the same city and district, the appellant usually did not name them, but limited himself to the general indication that he was signing “and for his comrades, elected people , place,” sometimes he signed for representatives from another city. Let us add that even among the elected officials named in the assaults, the social and official status of many remains unknown.

8) Among the elected officials (secular and clergy) known to us by their social status, representatives of the middle strata of the service class make up 50% (42 out of 84), clergy - more than 30% (26); In an incomparably smaller number, elected members of the townspeople (7) and instrumentalities (5) are known by name. But regarding the townspeople, in the assaults themselves there are indications that they were present as electors from many cities. None of the representatives of the peasantry are named.

9) Named in the assault are: 38 elected from 15 cities in Moscow, 16 elected from 7 Ukrainian cities, 13 elected from 5 cities in Zaotsk, 10 elected from 3 cities in the Ryazan region, 12 elected from 5 cities in Niza, "9 elected from 2 cities in Severg, 4 elected from 4 cities of the Field. Among the elected from the cities of Niz we include 4 Tatar “princes”, they gave assault in the Tatar language. One of them is Vasily Mirza, obviously a Christian.

Who this “Vasily Mirza” is can be seen from his petition, stored in the Moscow Archives of the Ministry of Justice: “To the Tsar, Sovereign and Grand Duke Mikhail Fedorovich of all Russia, your servant, the sovereign of the Kadomsky district, Tatar Vaska Murza Chermenteev beats with his forehead. Merciful Sovereign Tsar and Grand Duke Mikhail Fedorovich of all Russia, please grant me, your serf, for my service and for the joy that I, your serf, have been sent to Moscow to fleece the Tsar; and I, your servant, beat you, the sovereign, with my brow, about the letters, and you, the sovereign, granted me, your servant, the order to give your royal letters. Merciful sir, let me be your slave, do not impose a stamp duty on me, your slave, to assume that I, your servant, sir, am ruined to the ground. Tsar Sovereign and Grand Duke Mikhail Fedorovich of All Russia, have mercy, perhaps.” Note: “The Sovereign granted it, did not order duties on documents, therefore it sits with the Sovereign’s affairs in the Ambassadorial Prikaz in the Tatar translation. Duma deacon Peter Tretyakov" (Preobrazhensky order, column No. 1, l. 56, no date on the document). We meet this Murza Chermenteev, according to Archive documents, also as a Kadom landowner looking for runaway serfs. “In the summer of March 7133 (1625), on the 11th day, the sovereign’s letter was sent to Kadom to the governor on the petition of Kadomskovo Vasily Murza Chermonteyev against fugitive people on Ivashka Ivanov and on the zhonok on Okulka and on Nenilka, a trial was ordered. Duties of half a half were taken” (Printing Office Duty Book, No. 8, l. 675). His first petition shows that foreigners participated in the electoral council, which rejects the widespread scientific position that they only gave signatures on the document, but were not at the council.

On the Approved Certificate of Election, this Mirza signed, on one copy of it (as we read in the translation, at our request, again made now, with the participation of Prof. F.E. Korsh, by teachers of the Tatar language at the Moscow Lazarev Institute): “For the elected comrades from the fortress (city) of Tyumen and from the fortress (city) of Nadym, I, Vasily Mirza, put my hand”; or on another copy: “For the Kadom (?)... Simbirsk (? translators’ questions) people (I), Vasily Mirza, put his hand.” By Tyumen, obviously, one should mean one of the fortified cities, on the lower defensive line, to which Kadom belonged. Therefore, although the above-mentioned letter of notification to the Novgorod Metropolitan spoke of writing “to Siberia,” Mirza Vasily’s assault was “for the city of Tyumen” and “for the Simbirsk (Tyumen?) people” ( according to the previous translation, in the notes to the Approved charter of the Society, 88, 90) cannot, contrary to the opinion we previously expressed, serve as evidence of representation at the council of Siberia, in particular Tyumen.

Of the electives from Pomerania, only one “elected abbot Jonah from the Dvina Antonyev Monastery of Siisk” left his name on the charter, who, however, attested in his assault the presence of other electives from Pomerania. Of the lands stretching towards Pomerania, the representation of Vyatka (4) was relatively well reflected and the representation of Perm was not reflected at all. Of the cities from German Ukraine, only two cities were represented, lying in the southwestern corner of that region, Torzhok and Ostashkov. Of the cities from Lithuanian Ukraine, the presence of elected representatives from Vyazma and Toropets was certified; We learn about those elected from the latter not from the letter, but from another source - from reports about the ambassadors captured by Gonsevsky from Toropets (Archaeographic collection. Vilna, 1870, VII, No. 48, p. 73). - In the list made by P.G. Vasenko (note 27 to Chapter VI, “The Romanov Boyars and the Accession of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov.” St. Petersburg, 1913), cities, the presence of elected officials from which is certified by signatures on the charter, includes 43 cities; Staritsa, Kadom and Tyumen are not yet mentioned.

10) Among the elected representatives of 12 cities, the presence of “district people” was witnessed in assaults. Unfortunately, none of the latter are named. “District people” came to the council from almost all regions of the state; There are only no indications of their arrival from the German and Lithuanian Ukraine and from the Bottom. The “county people” from Pomerania included, of course, the peasants of the palace villages and black volosts, the elected representatives of whom were directly called to the council by a boyar charter to the Belozersk governor (Acts of the Moscow Region Militia, 99). However, in our opinion, the basis for the provision on calling peasants to the council in general cannot, in our opinion, be the second letter to Beloozero (ibid., 107), which refers to the previously named peasants, and the letter to Ostashkov (Arsenyev Swedish Papers, 19), as a translation , where there is no precision in the expressions, for example, instead of “county” there is “okrug”, etc. (See above, 14, note.) It is known that some researchers (for example, V. O. Klyuchevsky, Course of Russian history. M., 1908, III, p. 246): they mean “district people” who came from areas where there was no black peasantry, privately owned peasants. But it must be admitted that the presence at the council of 1613 of representatives of the privately owned peasantry would have little corresponded with the general situation of this peasantry at that time and would have been a sharp difference between the council of 1613 and subsequent zemstvo councils, at which there were undoubtedly no representatives of the privately owned peasantry.

Line UMK I. L. Andreeva, O. V. Volobueva. History (6-10)

Russian history

How did Mikhail Romanov end up on the Russian throne?

On July 21, 1613, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, Michael’s crowning ceremony took place, marking the founding of the new ruling dynasty of the Romanovs. How did it happen that Michael ended up on the throne, and what events preceded this? Read our material.On July 21, 1613, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, Michael’s crowning ceremony took place, marking the founding of the new ruling dynasty of the Romanovs. The ceremony, which took place in the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin, was carried out completely out of order. The reasons for this lay in the Time of Troubles, which disrupted all plans: Patriarch Filaret (by coincidence, the father of the future king), was captured by the Poles, the second head of the Church after him, Metropolitan Isidore, was in territory occupied by the Swedes. As a result, the wedding was performed by Metropolitan Ephraim, the third hierarch of the Russian Church, while the other heads gave their blessing.

So, how did it happen that Mikhail ended up on the Russian throne?

Events in the Tushino camp

In the autumn of 1609, a political crisis was observed in Tushino. The Polish king Sigismund III, who invaded Russia in September 1609, managed to split the Poles and Russians, united under the banner of False Dmitry II. Increasing disagreements, as well as the disdainful attitude of the nobles towards the impostor, forced False Dmitry II to flee from Tushin to Kaluga.On March 12, 1610, Russian troops solemnly entered Moscow under the leadership of the talented and young commander M. V. Skopin-Shuisky, the Tsar’s nephew. There was a chance of completely defeating the forces of the impostor, and then liberating the country from the troops of Sigismund III. However, on the eve of the Russian troops setting out on a campaign (April 1610), Skopin-Shuisky was poisoned at a feast and died two weeks later.

Alas, already on June 24, 1610, the Russians were completely defeated by Polish troops. At the beginning of July 1610, the troops of Zholkiewski approached Moscow from the west, and the troops of False Dmitry II again approached from the south. In this situation, on July 17, 1610, through the efforts of Zakhary Lyapunov (brother of the rebellious Ryazan nobleman P. P. Lyapunov) and his supporters, Shuisky was overthrown and on July 19, he was forcibly tonsured a monk (in order to prevent him from becoming king again in the future). Patriarch Hermogenes did not recognize this tonsure.

Seven Boyars

So, in July 1610, power in Moscow passed to the Boyar Duma, headed by boyar Mstislavsky. The new provisional government was called the “Seven Boyars”. It included representatives of the most noble families F. I. Mstislavsky, I. M. Vorotynsky, A. V. Trubetskoy, A. V. Golitsyn, I. N. Romanov, F. I. Sheremetev, B. M. Lykov.The balance of forces in the capital in July - August 1610 was as follows. Patriarch Hermogenes and his supporters opposed both the impostor and any foreigner on the Russian throne. Possible candidates were Prince V.V. Golitsyn or 14-year-old Mikhail Romanov, son of Metropolitan Philaret (former Patriarch of Tushino). This is how the name M.F. was heard for the first time. Romanova. Most of the boyars, led by Mstislavsky, nobles and merchants were in favor of inviting Prince Vladislav. They, firstly, did not want to have any of the boyars as king, remembering the unsuccessful experience of the reign of Godunov and Shuisky, secondly, they hoped to receive additional benefits and benefits from Vladislav, and thirdly, they feared ruin when the impostor ascended the throne. The lower classes of the city sought to place False Dmitry II on the throne.

On August 17, 1610, the Moscow government concluded an agreement with Hetman Zolkiewski on the terms of inviting the Polish prince Vladislav to the Russian throne. Sigismund III, under the pretext of unrest in Russia, did not let his son go to Moscow. In the capital, Hetman A. Gonsevsky gave orders on his behalf. The Polish king, possessing significant military strength, did not want to fulfill the conditions of the Russian side and decided to annex the Moscow state to his crown, depriving it of political independence. The boyar government was unable to prevent these plans, and a Polish garrison was brought into the capital.

Liberation from Polish-Lithuanian invaders

But already in 1612, Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, with part of the forces remaining near Moscow from the First Militia, defeated the Polish army near Moscow. The hopes of the boyars and Poles were not justified.You can read more about this episode in the material: "".

After the liberation of Moscow from the Polish-Lithuanian invaders at the end of October 1612, the combined regiments of the first and second militias formed a provisional government - the “Council of the Whole Land”, led by princes D. T. Trubetskoy and D. M. Pozharsky. The main goal of the Council was to assemble a representative Zemsky Sobor and elect a new king.In the second half of November, letters were sent to many cities with a request to send them to the capital by December 6 “ for state and zemstvo affairs"ten good people. Among them could be abbots of monasteries, archpriests, townspeople, and even black-growing peasants. They all had to be " reasonable and consistent", capable of " talk about state affairs freely and fearlessly, without any cunning».

In January 1613, the Zemsky Sobor began to hold its first meetings.

The most significant clergyman at the cathedral was Metropolitan Kirill of Rostov. This happened due to the fact that Patriarch Hermogenes died back in February 1613, Metropolitan Isidore of Novgorod was under the rule of the Swedes, Metropolitan Philaret was in Polish captivity, and Metropolitan Ephraim of Kazan did not want to go to the capital. Simple calculations based on the analysis of signatures under the charters show that at least 500 people were present at the Zemsky Sobor, representing various strata of Russian society from a variety of places. These included clergy, leaders and governors of the first and second militias, members of the Boyar Duma and the sovereign's court, as well as elected representatives from approximately 30 cities. They were able to express the opinion of the majority of the country's inhabitants, therefore the decision of the council was legitimate.

Who did they want to choose as king?

The final documents of the Zemsky Sobor indicate that a unanimous opinion on the candidacy of the future tsar was not developed immediately. Before the arrival of the leading boyars, the militia probably had a desire to elect Prince D.T. as the new sovereign. Trubetskoy.It was proposed to place some foreign prince on the Moscow throne, but the majority of the council participants resolutely declared that they were categorically against the Gentiles “because of their untruth and crime on the cross.” They also objected to Marina Mnishek and the son of False Dmitry II Ivan - they called them the “thieves’ queen” and the “thief”.

Why did the Romanovs have an advantage? Kinship issues

Gradually, the majority of voters came to the idea that the new sovereign should be from Moscow families and be related to the previous sovereigns. There were several such candidates: the most noble boyar - Prince F. I. Mstislavsky, boyar Prince I. M. Vorotynsky, princes Golitsyn, Cherkassky, boyars Romanovs.Voters expressed their decision as follows:« We came to the general idea of electing a relative of the righteous and great sovereign, the Tsar and Grand Duke, blessed in memory Fyodor Ivanovich of all Rus', so that it would be eternally and permanently the same as under him, the great sovereign, the Russian kingdom shone before all states like the sun and expanded on all sides, and many surrounding sovereigns became subject to him, the sovereign, in allegiance and obedience, and there was no blood or war under him, the sovereign, - all of us under his royal power lived in peace and prosperity».

In this regard, the Romanovs had only advantages. They were in double blood relationship with the previous kings. The great-grandmother of Ivan III was their representative Maria Goltyaeva, and the mother of the last tsar from the dynasty of Moscow princes Fyodor Ivanovich was Anastasia Zakharyina from the same family. Her brother was the famous boyar Nikita Romanovich, whose sons Fyodor, Alexander, Mikhail, Vasily and Ivan were cousins of Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich. True, due to the repressions of Tsar Boris Godunov, who suspected the Romanovs of an attempt on his life, Fedor was tonsured a monk and later became Metropolitan Philaret of Rostov. Alexander, Mikhail and Vasily died, only Ivan survived, having suffered from cerebral palsy since childhood; because of this illness, he was not fit to be king.

It can be assumed that most of the participants in the cathedral had never seen Michael, who was distinguished by his modesty and quiet disposition, and had not heard anything about him before. Since childhood, he had to experience many adversities. In 1601, at the age of four, he was separated from his parents and, together with his sister Tatyana, was sent to Belozersk prison. Only a year later, the emaciated and ragged prisoners were transferred to the village of Klin, Yuryevsky district, where they were allowed to live with their mother. Real liberation occurred only after the accession of False Dmitry I. In the summer of 1605, the Romanovs returned to the capital, to their boyar house on Varvarka. Filaret, by the will of the impostor, became the Metropolitan of Rostov, Ivan Nikitich received the rank of boyar, and Mikhail, due to his young age, was enlisted as a steward. The future tsar had to go through new tests during the Time of Troubles. In 1611 - 1612, towards the end of the siege of Kitai-Gorod and the Kremlin by militias, Mikhail and his mother had no food at all, so they even had to eat grass and tree bark. The elder sister Tatyana could not survive all this and died in 1611 at the age of 18. Mikhail miraculously survived, but his health was severely damaged. Due to scurvy, he gradually developed a disease in his legs.

Among the close relatives of the Romanovs were the princes Shuisky, Vorotynsky, Sitsky, Troyekurov, Shestunov, Lykov, Cherkassky, Repnin, as well as the boyars Godunov, Morozov, Saltykov, Kolychev. All together they formed a powerful coalition at the sovereign’s court and were not averse to placing their protege on the throne.

Announcement of the election of Michael as Tsar: details

The official announcement of the election of the sovereign took place on February 21, 1613. Archbishop Theodoret with clergy and boyar V.P. Morozov came to the Place of Execution on Red Square. They informed Muscovites the name of the new tsar - Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. This news was met with general rejoicing, and then messengers dispersed to the cities with a joyful message and the text of the sign of the cross, which the residents had to sign.The representative embassy went to the chosen one only on March 2. It was headed by Archbishop Theodoret and boyar F.I. Sheremetev. They had to inform Mikhail and his mother of the decision of the Zemsky Sobor, obtain their consent to “sit on the kingdom” and bring the chosen ones to Moscow.

On the morning of March 14, in ceremonial clothes, with images and crosses, the ambassadors moved to the Kostroma Ipatiev Monastery, where Mikhail and his mother were. Having met at the gates of the monastery with the people's chosen one and Elder Martha, they saw on their faces not joy, but tears and indignation. Michael categorically refused to accept the honor bestowed on him by the council, and his mother did not want to bless him for the kingdom. I had to beg them for a whole day. Only when the ambassadors stated that there was no other candidate for the throne and that Michael’s refusal would lead to new bloodshed and unrest in the country, Martha agreed to bless her son. In the monastery cathedral, the ceremony of naming the chosen one to the kingdom took place, and Theodoret handed him a scepter - a symbol of royal power.

Sources:

- Morozova L.E. Election to the kingdom // Russian history. - 2013. - No. 1. - P. 40-45.

- Danilov A.G. New phenomena in the organization of power in Russia during the Time of Troubles // Questions of history. - 2013. - No. 11. - P. 78-96.

Results of the Troubles were depressing: the country was in a terrible situation, the treasury was ruined, trade and crafts were in decline. The consequences of the Troubles for Russia were expressed in its backwardness compared to European countries. It took decades to restore the economy.

№11 The main trends in the socio-economic and political development of Russia inXVIIV.

After the Time of Troubles, Russia underwent a restoration process for almost three decades. Only from the middle of the 17th century. New, progressive trends begin to appear in the economy. As a result of the defeat of the Golden Horde, the fertile lands of the Black Earth Center and the Middle Volga region were brought into economic circulation. Due to their relatively high yield, they produce some surplus grain. This surplus is sold to less fertile regions, allowing their population to gradually move on to other occupations that are more appropriate to the local climatic conditions. Process in progresszoning- economic specialization of various regions. In the north-west, in the Novgorod, Pskov, and Smolensk lands, flax and other industrial crops are cultivated. The northeast - Yaroslavl, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod lands - begins to specialize in cattle breeding. Peasant crafts are also developing noticeably in these regions: weaving in the northwest, leather tanning in the northeast. The increasing exchange of agricultural and commercial products, the development of commodity-money relations lead to the gradual formation of the internal market (the process is completed only by the end of the 17th century). Trade in the 17th century. was mainly of a fair nature. Some fairs were of national importance: Makaryevskaya (near Nizhny Novgorod), Irbitskaya (Southern Urals) and Svenskaya (near Bryansk). A new phenomenon in the economy has becomemanufactories- large-scale production with division of labor, still mostly manual. Number of manufactories in Russia in the 17th century. did not exceed 30; the only industry in which they arose was metallurgy.

Socially The nobility is becoming an increasingly significant force. By continuing to give land to service people for their service, the government avoids taking them away. Increasingly, estates are inherited, i.e. are becoming more and more like fiefdoms. True, in the 17th century. this process has not yet been supported by special decrees. The peasantry in 1649 was finally attached to the land by the Council Code: St. George's Day was canceled forever; the search for fugitives became indefinite. This enslavement was still of a formal nature - the state did not have the strength to actually attach the peasantry to the land. Until the beginning of the 18th century. They wandered around Rus' in search of a better life for a gang of “walking people”. The authorities are taking measures to support the “merchant class”, especially its privileged elite - the guests. In 1653 it was adoptedTrade charter, replacing many small trade duties with one, in the amount of 5% of the price of the goods sold. Competitors of Russian merchants - foreigners - had to pay 8%, and according to the New Trade Charter of 1667 - 10%.

In terms of political development of the 17th century. was the time of formation of the autocratic system. The tsarist power gradually weakened and abolished the class-representative bodies that limited it. Zemsky Sobors, to whose support after the Time of Troubles the first Romanov, Mikhail, turned almost every year, under his successor Alexei stop convening(the last council was convened in 1653). The tsarist government skillfully takes control of the Boyar Duma, introducing Duma clerks and nobles into it(up to 30% of the composition), unconditionally supporting the king. Proof of the increased strength of tsarist power and the weakening of the boyars was the abolition of localism in 1682. The administrative bureaucracy, which served as a support for the tsar, strengthened and expanded. The order system becomes cumbersome and clumsy: by the end of the 17th century. there were more than 40 orders, some of them were functional in nature - Ambassadorial, Local, Streletsky, etc., and some were territorial - Siberian, Kazan, Little Russian, etc. An attempt to control this colossus with the help of the Secret Affairs order was unsuccessful. On the ground in the 17th century. Elected governing bodies are finally becoming obsolete. All power passes into the hands ofto the governors, appointed from the center and livingfeedingat the expense of the local population. In the second half of the 17th century. In Russia, regiments of a new system appeared, in which “willing people” - volunteers - served for a salary. At the same time, the Eagle was built on the Volga - the first ship capable of withstanding sea voyages.

№12 Church reform of the second half of the 17th century, the split of the Russian Orthodox Church (causes and consequences).

SplitleftonbodyRussiadeep, non-healingscarring. INresultstruggleWithsplitdiedthousandsof people, VvolumenumberAndchildren. Carried overheavyflour, distortedfatethousandsof people.

In general, the split movement is a reactionary movement. It hindered progress and the unification of Russian lands into a single state. At the same time, the split showed the resilience, courage, of large groups of the population in defending their views, faith, (preservation of the ancient way of life, orders established by their ancestors).

Schism is part of our history. And we contemporaries need to know our history and take everything good and decent from the old days. And in our time, especially in recent years, our spirituality is under threat.

OccasionForemergencesplit, Howknown, servedchurchly- ritualreform, whichV 1653 yearbeganconductpatriarchNikonWithpurposefortificationschurchorganizationsVRussia, ASosameliquidateAlldisagreementsbetweenregionalOrthodoxchurches.

ChurchreformbeforeTotalstartedWithcorrectionsRussiansliturgicalbooksByGreekAndOld SlavonicsamplesAndchurchrituals.

Next heenteredonplaceancientMoscowunison (one-voice) singingnewKievpolyphonic, ASosamestartedunprecedentedcustompronounceVchurchessermonsownessays.

These orders from Nikon forced the believers to conclude that they had hitherto neither known how to pray nor paint icons, and that the clergy did not know how to perform divine services properly.

Onefromcontemporariestells, HowNikonactedagainstnewiconography.

Although the reform affected only the external ritual side of religion, but in conditions of great importance of religion in the public life of the population, everyday life, etc. These innovationsNikonpainfulwere acceptedtops, especiallyrural, patriarchalpeasants, Andespeciallygrassrootslinkclergy. The ritual of “three fingers”, the pronunciation of “Hallelujah” three times instead of two, bows during worship, Jesus instead of Jesus were never accepted by all the elites. Definitely, although the innovations were adopted not only on Nikon’s initiative, but also approved by church councils of 1654-55.

Discontentinnovationschurches, ASosameviolentmeasurestheirimplementationappearedreasonToschism. Firstbehind « oldfaith» againstreformsAndactionspatriarchspokearchpriestHabakkukAndDaniel. They submitted a note to the king in defense of two fingers and about bowing during worship and prayers. Then they began to argue that making corrections to books based on Greek models desecrates the true faith, since the Greek Church apostatized from “ancient piety”, and its books are printed in Catholic printing houses. Ivan Neronov, without touching on the ritual side of the reform, opposed the strengthening of the power of the patriarch and for a simpler, more democratic scheme for governing the church.

№13 Sophia's reign. Reform projects by V. Golitsyn.

INgoverning bodySophiawerecarried outmilitaryAndtaxreforms, developedindustry, was encouragedtradeWithforeignstates. Golitsyn, becamerighthandprincesses, broughtVRussiaforeignmasters, famousteachersAndartists, encouragedimplementationVcountryforeignexperience.

The princess appointed Golitsyn as military leader and insisted that he go on the Crimean campaigns in 1687 and 1689.

Having grown up and having a very contradictory and stubborn character, Peter no longer wanted to listen to his domineering sister in everything. He contradicted her more and more often, reproached her for excessive independence and courage, not inherent in women, and listened more and more to his mother, who told her son the long-standing story of the accession to the throne of the cunning and insidious Sophia. In addition, the state papers stated that the regent would be deprived of the opportunity to govern the state if Peter came of age or got married. By that time, the heir already had a young wife, Evdokia, but his sister, Sofya Alekseevna Romanova, still remained on the throne.

Seventeen-year-old Peter became the most dangerous enemy for the ruler, and she, as the first time, decided to resort to the help of the archers. However, this time the princess miscalculated: the archers no longer believed either her or her favorite, giving preference to the young heir. INendSeptemberTheyswore allegianceonloyaltyPetru, AThatorderedto concludesisterVNovodevichymonastery. So the thirty-two-year-old princess was removed from power and forever separated from her lover. VasilyGolitsynadeprivedboyartitle, propertyAndranksAndexiledVlinkVdistantArkhangelskvillage, Whereprincelivedbeforeendtheirdays.

Sophia was tonsured a nun and took the name Susanna. She lived in the monastery for fifteen long years and died on July 4, 1704. Her lover, favorite and beloved friend outlived the former princess and ruler of the Russian State by ten years and died in 1714.

№14 Reforms of the early 18th century. and the birth of the Russian Empire

In 1611, Patriarch Hermogenes, calling on the sons of the church to defend the fatherland, insisted on electing a Russian tsar, convincing him with examples from history; but he was starved to death for this call, his life expired on February 17, 1612, but he died with the name of Michael, indicating who should be king.

- By the end of 1612, Moscow and all of central Russia, notified by the leaders of the people's militia, celebrated their salvation and, triumphantly, remembered the dying testament of Patriarch Hermogenes - on February 21, 1613, the unanimous choice for king fell on Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov, the son of the former Rostov Metropolitan Filaret Nikitich, who was still languishing in captivity among the Poles and returned from there only in 1619.

— The first act of the great Zemsky Sobor, which elected sixteen-year-old Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov to the Russian throne, was to send an embassy to the newly elected tsar. When sending the embassy, the cathedral did not know where Mikhail was, and therefore the order given to the ambassadors said: “Go to Sovereign Mikhail Fedorovich, Tsar and Grand Duke of All Rus' in Yaroslavl.” Arriving in Yaroslavl, the embassy here only learned that Mikhail Fedorovich lives with his mother in Kostroma; without hesitation, it moved there, along with many Yaroslavl citizens who had already joined here.

— The embassy arrived in Kostroma on March 14; On the 19th, having convinced Mikhail to accept the royal crown, they left Kostroma with him, and on the 21st they all arrived in Yaroslavl. Here all the residents of Yaroslavl and the nobles who had come from everywhere, boyar children, guests, trading people with their wives and children met the new king with a procession of the cross, bringing him icons, bread and salt, and rich gifts. Mikhail Fedorovich chose the ancient Spaso-Preobrazhensky Monastery as his place of stay here. Here, in the archimandrite’s cells, he lived with his mother nun Martha and the temporary State Council, which was composed of Prince Ivan Borisovich Cherkassky with other nobles and clerk Ivan Bolotnikov with stewards and solicitors. From here, on March 23, the first letter from the tsar was sent to Moscow, informing the Zemsky Sobor of its consent to accept the royal crown. The warm weather that followed and the flooding of the rivers detained the young tsar in Yaroslavl “until it dried out.” Having received information here that the Swedes from Novgorod were going to Tikhvin, Mikhail Fedorovich from here sent Prince Prozorovsky and Velyaminov to defend this city, and sent an order to Moscow to detach troops against Zarutsky, who, having robbed Ukrainian cities, with a crowd of rebels and Marina Mnishek was going to Voronezh . Finally, on April 16, having prayed to the Yaroslavl Wonderworkers and accepting a blessing from Spassky Archimandrite Theophilus, accompanied by the good wishes of the people, with the bells of all churches ringing, Mikhail Fedorovich left the hospitable monastery in which he lived for 26 days. Soon after his arrival in Moscow, in the same 1613, Mikhail Fedorovich sent three letters of grant to the Spassky Monastery, as a result of which the welfare of the monastery, which suffered a lot during the Polish defeat, improved. And throughout his reign, the sovereign constantly had affection for Yaroslavl and remembered the place of his temporary stay. Proof of this is 15 more letters of grant given to the same monastery.

- In the first years after the accession of Mikhail Fedorovich, before the final conclusion of peace with Poland, Yaroslavl with its environs and neighboring cities often had to endure great disturbances from the Poles, and in 1615 Yaroslavl again became a rallying point for troops equipping themselves against Lisovsky, who was then troubling Uglich, Kashin, Bezhetsk, Romanov, Poshekhonye and the surrounding area of Yaroslavl. In 1617, Yaroslavl was in danger from the Zaporozhye Cossacks, sent here from near the Trinity Lavra by the Polish prince Vladislav, who again decided to seek the Russian throne. Boyar Ivan Vasilyevich Cherkassky drove them away from here “with great damage.”

— Filaret Nikitich, who returned from captivity in 1619, was installed as patriarch of the Russian church, and the following year the tsar undertook a “prayer journey” through the cities, and visited Yaroslavl.

K. D. Golovshchikov - "History of the city of Yaroslavl" - 1889.