History of the French language: origin and distinctive features, interesting facts. A brief history of the formation of the French language Write an article on the topic of the history of the French language

Modern French belongs to the group of so-called “Romance” languages. Derived from Latin, these languages can be said to represent living shadows of the ancient Roman Empire, reflecting the different histories of the regions formerly united under Roman rule.

The source of modern French (and other Romance languages) was an oral, vernacular version of Latin that was spread to other lands through the conquest of Roman legions, namely, in the case of French, the so-called "Transalpine Gaul" by the armies of Julius Caesar in the centuries preceding birth of Christ.

Invasion of Gaul in 400 AD Germanic tribes (including the so-called "Franks") fleeing from attacking nomads from Central Asia led to the loss of military control by Rome and the creation of a new ruling class of Franks, whose native language was, of course, not Latin. Their adaptation to speaking vernacular Latin sought to impose their language on the indigenous population by authoritative example; a pronunciation that carries the characteristics of Germanic languages - especially the vowel sounds that can be heard in modern French (modern French "u" and "eu", for example, are still very close to modern German "u" and " o" – sounds not found in other modern languages descended from Latin).

Changes in grammar gradually made Latin more difficult for modern speakers to understand, but Latin was still used in Christian religious services and in legal documents. As a consequence, a written codification of the developing spoken language was found, necessary for its current legal and political use. The earliest written documents in a language we can understand in "Francien" are the so-called "Oaths of Strasbourg", the oaths of two grandsons of Charlemagne in 842 AD.

This "French" language was actually one of a number of different languages descended from Latin, which was spoken in various parts of post-Roman Gaul. Others included in particular the so-called "Provençal" language (or "language d'oc"), spoken by a large part of the southern half of today's metropolitan France. However, the so-called "French" language acquired a special status as a result of its association with the dominant feudal military power - namely the court of Charlemagne and his successors, whose territorial reach and effective control of French life grew over time.

The return of the French court to Paris - after its transfer to Aachen (Aachen) under Charlemagne, and the eventual success of the army against the Anglo-Norman conquerors of the main parts of northern and southwestern France, led to territorial consolidation which guaranteed the future position of the "French "as the official language of a centralized monarchy (later the nation-state). French was approved by the Decree of Villers-Cottrets in 1539.

The poetic fertility of the medieval Provençal language, which had far surpassed the French language in the so-called period of the Troubadours, now gave way to the literary productivity of the language of the central court and the central institutions of justice and learning - the language of Paris and the surrounding region of Ile-de-France.

The grammar of spoken and written French today is essentially unchanged since the late 17th century, when official efforts to standardize, stabilize, and clarify the use of French grammar were organized at the French Academy. The purpose of this was political standardization: to facilitate the spread of court influence and smooth the workings of law, government and commerce throughout France, even beyond its borders, as colonial enterprises (like India and Louisiana) opened up new theaters of imperial growth.

Even today, after the decline of French imperial influence after World War II, French remains the second language of the overwhelmingly "French-speaking" population, spread far beyond the remaining French islands and dependencies (French Guiana, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tahiti, Seychelles, Mauritius and Reunion).

Brief answers to the French language theory course, Moscow State Pedagogical University, 3rd year.

1) Problems and methods of studying the history of the French language. Course on the history of the French language, its subject and objectives. External and internal history of the language. Problems of periodization of the history of the French language.

Neogrammatism and structuralism in historical studies of the French language. Chronological and aspectual principles of constructing a course on the history of language.

2) Background of the French language. Romanization of Gaul. The concept of folk (vulgar) Latin.3) The problem of the origin of the French language. French is one of the Romance languages. Existing classifications of Romance languages. Folk Latin as the source of the origin of the Romance languages. Gallo-Roman period (V -VIII centuries). The nature of bilingualism in Gaul and its consequences.

The main changes in the field of pronunciation in the folk Latin of Northern Gaul: diphthongization of stressed vowels, loss of unstressed vowels as an expression of the tendency towards oxytonic stress, development of affricates, simplification of consonant groups (a tendency towards openness of the syllable, characteristic of the sound system of the French language). 4) Historical conditions of education French language. The structure of Vulgar Latin: phonetics, morphology, syntax, vocabulary. Major changes in the field of grammatical structure: the development of analytical trends in the noun system, adjective system, pronouns and verb system.

The first historical evidence and monuments of the French language (Strasbourg oaths).5) Old French period. External history of France (IX-XIII centuries).

Feudal fragmentation. The concept of language and dialect in the Old French period. Old French dialects and their characteristics. Presence of dialect groups (western and northeastern). Place of Champagne and Picard dialects.

Bilingualism in the Old French period. The sphere of distribution of Latin and French languages in this period.

The first written monuments of the French language, their genre characteristics. Dialects and script. The contribution of scriptology to the history of the French language.6) The phonetic system of the Old French language. Basic phonetic processes in the Old French period. The concept of phonetic law. Features of graphics and spelling.

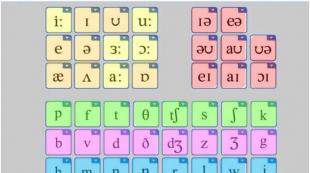

7) Sound structure. Vocalism. The appearance of qualitative differences in vowels. Timbre differences between vowels [e] and [o]. The question of the presence of the phoneme [u] in the system of vocalism (before the 13th century). Nasalized vowels as variants of pure vowels. System of diphthongs, primary and secondary diphthongs. Presence of triphthongs.

Consonantism. Affricates, interdental fricatives, consonants of Germanic origin.

The main development trends: contraction of diphthongs, elimination of consonant groups, vocalization of [l] before consonants, disappearance of [s] before a consonant and the final [t] after a vowel.

Features of graphics and spelling.8) The grammatical system of the Old French language. Inflectional and analytical morphology of the word.

9) Noun. Grammatical categories of gender, number, case. The beginning of the formalization of the categories of certainty and uncertainty. Choice of form and use of articles. The meaning of the so-called partitive article (del pain).

10) Adjective. Coordination categories of gender and number. Category of degrees of comparison, formation of analytical forms of comparison of adjectives.

11) Pronoun. Personal pronouns, declension paradigms. Features of the use of subjective pronouns.

12) Possessive pronouns. The main cases of using parallel (independent, non-independent) forms of possessive pronouns.

13) Demonstrative pronouns. Relative and indefinite pronouns.

14) Numeral. The formation of the numeral system in the Old French period.

15) Verb. Non-personal and personal forms. Development of personal verb forms. Analytical and inflectional forms of the verb. Categories of tense, aspect, mood and voice in Old French. Verb conjugation, infectious and perfect stems. Use of tenses and moods.

16) Adjective. Expression of grammatical gender by adjectives.17) Syntax of simple and complex sentences in the Old French period. Word order in Old French sentences. Development of means of composition and subordination in the Old French period.

18) Build sentences. The main syntactic units are simple and complex (complex) sentences.

A simple sentence, its structure. Word order as the main structural feature of a simple sentence.

Difficult sentence. Problems of development and its classification. Development of means of composition and subordination in the Old French period. The influence of coordinating conjunctions on word order.

Complex sentence and its types. Structural features of a complex sentence. Features of the structure of additional, temporary, conditional sentences. Subordinating conjunctions and methods of their formation in the 12th - 13th centuries. Relative clauses and their structural and semantic varieties. 19) Dictionary of the Old French language. Analysis of the structure of the dictionary by: a) etymological groups; b) word formation models; c) lexical-semantic groups. Word formation models. Suffixation and prefixation as the main methods of word formation in the Old French period. Poor development of word composition. The original fund of the French language of the early period, its constituent elements. The role of the Latin language in word formation and the formation of terminology in the Old French period.20) Middle French period (XIV-XV centuries). External history of the French language. Problems of bilingualism. Latin language in France in the XIV-XV centuries. Bilingualism in administrative correspondence and legal proceedings: the use of French along with Latin. 21) Specificity of sound, grammatical structure and sentence structure in the XIV-XV centuries.

Internal and external factors in the development of the phonetic system. Changes in the vowel system. Phonologization of qualitative vowel differences. Tendency to lose vowels in gape. Monophthongization. Denasalization.

Changes in the consonant system. Simplification of affricates. The beginning of weakening of final consonants in the flow of speech, emerging shifts in the nature of stress.

Spelling and principles of its construction. The first attempts to establish spelling norms for the French written language. The role of etymologization. False etymology. Morphological principle in spelling. Diacritics.

22) Grammar system. Morphology of the word in the Middle French period.

Changes in the noun system. Final loss of case inflection. Continuation of the process of formalizing the category of certainty/uncertainty. Development of a new category of countability/non-countability (change in the meaning of the partitive article).

23) Pronoun. Continuation and strengthening of the process of differentiation of pronouns-nouns and pronouns-adjectives.

24) Verb. Weakening the role of inflection as a way of expressing number and person: strengthening verb pronouns in this role. Category of time: differentiation of time relations. Mood category: continuation of narrowing the scope of use of subjonctif, displacing it from conditional sentences. Development of forms of collateral. Development of combinations of personal forms of the verbs aller and venir with the infinitive to express the beginning and completion of an action.

25) Build sentences. Increasing tendency to establish a fixed word order. The relative clause as the main obstacle to fixing direct word order (frequent inversion of the nominal subject). Complication of subordinating connections in the system of complex sentences, intensive process of formation of subordinating conjunctions, clarification of their meaning. 26) Early French period (XVI century). Place and role of the 16th century. like the century of the French Renaissance in the history of France. The formation of the French national written and literary language. The Villers-Cotterets Ordinance as a legal designation of the French language as the state language; their displacement of the Latin language.

27) The role of translators of the XIV-XVI centuries. in preparation for the French Renaissance. The first French grammars and the first projects of spelling reform (Jacques Dubois, Louis Maigret, Robert and Henri Etienne, Pierre Ramus) as the first attempts to codify the norms of the general French written and literary language. Social foundations of codification.

28) Activities of the Pleiades. Manifesto by I. Du Bellay. Italianization of society and language.

29) Vocabulary. Development of terminology. The role of Latin and Greek in this process. The phenomenon of relatinization.30) New French period (XVII - XVIII centuries). The 17th century in France is a period of absolutism and centralization, classicism, as well as normalization in language.

Language theories of F. Malherbe and C. Vozhla. Dictionary of the French Academy and A. Furetier's dictionary (Dictionnaire universel).

Purism and prezioznitsy. The role of writers in the formation of norms of the French written and literary language.

Diderot and Encyclopedia. Development of grammatical theory in the 18th century: rationalistic grammar of Port-Royal.

Revolution of 1789, language policy of the Convention.31) The French language system in the 17th-18th centuries. Grammatical structure. Dictionary. The growth of philosophical and political terminology.

Phonetic system. Further development of qualitative differences in vowels. Completion of the formation of the modern nasal vowel system. Violation of the tendency towards openness of the syllable due to the penetration of numerous Latin and Italian borrowings. Competition between literary and colloquial pronunciations.

32) Grammatical structure. Analytical trends in various parts of speech. Final formulation of the categories of definiteness/indeterminacy, countability/uncountability of a noun. Development of a complex system of function words forming a noun and a verb. Inflectional forms in the system of verbs and nouns as survival phenomena. The final distinction between the forms of demonstrative, possessive and reflexive pronouns.

Completion of the process of unification of verb forms (disappearance of doublet forms). Completing the differentiation in the use of passé antérieur and plus-que-parfait. The relationship between the use of the forms passé simple and passé composé. Expanding the scope of use of super complex tenses.

A variety of means of expressing passive action (construction with the verb être, pronominal verbs, impersonal phrases). Distinction in the use of forms in -ant.

33) Build sentences. Complicating the ways of expressing a question (spreading the phrase est-ce que). Development of a complex sentence.

34) Dictionary. Development of terminology. Continuation of the formation of word-formation types on a book basis. The growth of borrowings from English in the 18th century.

35) Conclusion on the course on the history of the French language. Trends in the development of the French language in the 19th-20th centuries. Francophonie.

Description of the presentation by individual slides:

1 slide

Slide description:

Research project on the topic: History of the development of the French language Performers: Luzina Vladislava Igorevna 11 “B”, Kalashnikova Irina Olegovna 11 “A” Supervisor: Davydova A.A. French teacher 2

2 slide

Slide description:

Purpose: Acquaintance with the origin and development of the French language. Objectives: get acquainted with the origin of the French language and the stages of its development; establish ways to enrich the French language; learn about national characteristics of color perception in phraseological units; get acquainted with the language of French youth and youth slang; *

3 slide

Slide description:

French language French is a Romance language. It comes from the Latin language, which gradually replaced the Gaulish language in the territory of Gaul. Today, French is spoken by about 130 million people in the world. Latin group French language Moldovan language Italian language Spanish language Romanian language * 2

4 slide

Slide description:

Francophonie The concept of “Francophonie” was introduced in 1880 by the French geographer O. Reclus (1837-1916), who studied mainly France and North Africa. This concept has 2 main meanings: the fact of using the French language; the totality of the French-speaking population (France, Belgium, Switzerland, Canada, Africa, etc.) Regions with a large number of French speakers: Sub-Saharan Africa 76% Maghreb 70% Western Europe 20% Regions with an average number: North America 13% 3. Regions with a low by number: Near and Middle East 11% Eastern Europe 5% Latin America and the Caribbean 3% Regions with very low numbers: French-speaking Africa 2.6% Asia and Oceania 0.2% * 2

5 slide

Slide description:

Origins and stages of development of the French language In the 9th century, French territory was divided into 3 large regions: the region of the Provencal (Occitan) language, the Franco-Provencal region and the region of the Nangdoil language. In the 13th century, the French language emerged from the Francian dialect. In the 16th century, the most important government act prescribed the use of exclusively French in all court documents. In the 17th century, the French language was enriched with many layers borrowed from Greek and Latin: Bibliothecarius - bibliotheque (library) Spectaculum - spectacle (performance) Familia - famille (family) Studens, entis - etudiant (student) In 1635, the French Academy was founded; she was entrusted with an important mission: to create an explanatory dictionary and its grammar. Since the 17th century, French has become a universal language in Europe. * 2

6 slide

Slide description:

Ways to enrich the French language Borrowing words of Frankish origin. Foreign language contribution to vocabulary. modern French. Transferring proper names to common nouns. Youth slang. *

Slide 7

Slide description:

1. Borrowing words of Frankish origin. a) without changing the lexical meaning of the word: bleu, flot, trop, robe, salle, frais, jardin etc. b) with changes: batir “bastjan”, banc, trop “ro”, fauteuil c) creation of derivatives from Old Frankish words: “turner” – tourner, “graim” – chagrin, “glier” - glisser *

8 slide

Slide description:

2. Foreign language contribution to the vocabulary The French language has many words borrowed from other languages. The words used in French come from: Arabic: l"alcool, le café, ajouré; English: parking, humour, cinéma, sport; German: nouilles, joker; Greek: thermomètre, l"architecture, la machine; Italian: piano, d'un balcon, un carnaval; Spanish: chocolat, tomate, tabac, caramel; Russian: compagnon, un samovar, chalet, matriochka. The Russian language has a slight influence on French vocabulary: Beluga, le rouble, un manteau en peau de mouton, une grand-mère, un rouleau, boulettes de pâte, de résidence, la perestroïka, la glasnost. Borrowings from the French language are significant in Russian and are divided into different thematic groups: furniture (lampshade, wardrobe, dressing table); suit, corset, coat); accessories (bracelet, veil); politics (liberal, communism, federation); culture (impressionism, memoirs, actor, repertoire); cooking (broth, dessert, cutlet, marinade *). 2

Slide 9

Slide description:

3. Transfer of proper names to common nouns. a) family names: La Tour Eiffel, cadillac, soubise, fiacre b) transfer of geographical names to objects of material reality: fabric: tulle food: roquefort, plombieres plants: mirabelle * 2

10 slide

Slide description:

11 slide

Slide description:

Slang of modern French youth Examples of “fashionable” words among young people: pote – copain; bosser – travailler; For 15-17 year olds, “verlan” is typical: métro – tromé; musique – zicmu; “Largonzhi”: cher – lerche; prince –linspré; Abbreviations: a) “apokope”: graff – graffiti; Net – Internet; b) “apheresis”: blème – problème; dwich – sandwich; c) “alphabetisms”: M.J.C. – Maison des Jeunes et de la Culture; “acronyms”: la BU – la Bibliotheque Universitaire; Confluence: école + colle = écolle; Some words are borrowed from: Arabic: kawa = café; clebs = chien; Berber: arioul – idiot; Gypsy: bédo – cigarette de haschisch; Creole: timal – gars; African: gorette – fille; English: driver – chauffeur de taxi. * 2

12 slide

Slide description:

Peculiarities of color perception in phraseological units Blue: “sang bleu”, “reve bleu”, “l'oiseau bleu”, “peur bleu”, “contes bleus” Green: “temps vert”, “etre vert de froid”, “en dire” des verts” Yellow: “sourire jaune”, “jaune comme un citron” White: “boule blanche”, “carte blanche” Red: “rouge comme un tomate”, etre en rouge” Black: “humour noir”, “machines” noires” * 2

Folk Latin

Before the conquest by Rome, the Gauls, tribes of the Celtic group, lived on the territory of what is now France. When Gaul, as a result of the wars of Julius Caesar, became one of the Roman provinces (II-I centuries BC), Latin began to penetrate there along with imperial officials, soldiers and traders.

Gaul within the Roman Empire. The city of Lutetia, the “capital” of the Celtic tribe of Parisians, is the future Paris.

Over the five centuries that Gaul belonged to Rome, the local people gradually “Romanized”, i.e. assimilates with the Romans and switches to their language, which by that time is at a high level of development and dominates a vast territory. At the same time, the Gallo-Roman population retains in their speech the so-called Celtic substrate (i.e., traces of the disappeared ancient local language; a number of Celtic words can still be found in French today: charrue - plow; soc - opener; chemin - path, road, path; claie - wickerwork, fence). From this moment on, the conquered Gauls were already called Gallo-Romans. The Latin language itself is also enriched by languages that later disappeared without a trace into the conglomerate that was the ancient empire.

Gradually, the spoken language of the citizens of Rome moves away from the classical examples of Cicero and Ovid. And if before the beginning of the decline of Rome, the colloquial language (that same folk Latin) remained just a stylistic variety of the classical one, since official documents were still written in the correct, classical language, then with the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire and the invasion of the barbarians (approximately III- V centuries AD) dialectical differences began to multiply. And after the fall of the Roman Empire (476 AD), there was no single center, and the popular spoken language - folk Latin - in the “fragments” of the Roman Empire began to develop everywhere in its own way.

But all this did not happen in one day, year or even century. We can say that folk Latin turned from a single, more or less understandable language into separate - Romance - languages over 5-6 centuries, i.e. by the 9th century AD After the 9th century Vernacular Latin no longer exists, and from this point on individual Romance languages are considered.

But let's return to the era of the Empire.

Shortly before the fall of Rome, barbarians penetrate into the territory of what is now France, inhabited by Romanized Gauls, and the language of the Gallo-Romans for the first time encounters Germanic linguistic pressure. However, Latin, even if it is already folk, is winning.

After the fall of Rome (5th century AD), Gaul was conquered by Germanic tribes - the Visigoths, Burgundians and Franks.

It was the Franks who turned out to be the strongest, just remember their leaders - Clovis I or Charlemagne (thanks to him, by the way, the word king came into the Russian language - this is how his name was pronounced in Latin: Carolus).

It was they, the Franks, who ultimately gave the country its modern name.

The coexistence of the conquering Franks and the conquered Gallo-Romans led, naturally, to a serious linguistic confrontation that lasted four centuries (V-IX), and, at first glance, a historical paradox occurred: the popular Latin language, as a more developed dialect, turned out to be stronger than the sword of the Germans , and by the 9th century. from folk Latin in the north of France a new, common (for the indigenous population of the Gallo-Romans and the Franks who came here) language was formed - French (or rather, Old French), and in the south - Provençal.

From folk Latin to Old French (V - IX centuries)

During the period of popular Latin, which began with the decline of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. and before the formation of the Old French language in the 9th century, Latin vowels in open syllables were “diphthongized” under stress (recall that diphthongs are stable combinations of two letters, read the same in almost all cases; the pronunciation of a diphthong often does not coincide with the reading of its constituents letters in the alphabet), i.e. mel ⇒ miel (honey), fer ⇒ fier (proud), (h)ora ⇒ (h)uore (hour), flore ⇒ fluore (flower). In a number of words there is a transition a ⇒ e: mare ⇒ mer (sea), clare ⇒ cler (clear, clean, now spelled claire). The pronunciation of Latin u turns into French [ü] (as in the word tu - you). There is also a loss of unstressed vowels at the end of words - for example, the Latin camera turned into tsambre, and then into chambre (room).

It is interesting that during this period, c before i and e began to be read as Italian [c] (Latin cinque began to be read as [cinque], for example), and before the vowel a, the letter c began to be read as [h], i.e. from the Latin cantar (to sing) came [chantar]; Subsequently, this sound will begin to be read as [w], a will turn into e, and we will get the modern verb chanter - voilà!

It is noteworthy that during this period the combination s + another consonant is still preserved, but in other combinations of consonants - for example, pt and ct (the ancient Romans loved many consonants in words next to each other) - one of the letters tends to fall out, which is why septe turns into set ( seven), sanctu - in saint (holy).

During the same period, the Latin combination qu before i and e lost the sound [u], i.e. The ancestors of the French had already stopped “croaking”: the Latin qui [qui] began to be pronounced as [ki] (who). By the 12th century, the “croaking” would cease before other vowels (quatre would become [quatre]). It is noteworthy that the Spaniards will stop “croaking” several centuries later, but the Italians are still “croaking”, they say qui [qui].

In the V-IX centuries. In the folk Latin language, two cases are still preserved - the nominative case and the case, which replaced all indirect forms (there were 6 cases in total in Latin).

Why is the history of the French language (and other Romance languages) counted from the 9th century? Because then the first document appeared in Old French - the “Strasbourg Oaths” - which was signed by the grandchildren of Charlemagne. Having analyzed the “Oaths,” linguists make an unambiguous conclusion that the new language is a “descendant” of Latin. At the same moment, a separate French nation began to form in France (as opposed to the ethnic group that was formed across the Rhine and spoke a Germanic dialect - the future Germans).

Old French

For a long time, the natural border between Old French and Provençal was the Loire River. And although, as we found out, Latin, albeit vulgar, won, and the new language was Romance, the close proximity of the northern, Old French dialect to the Germanic peoples led to the fact that the language of the north was more susceptible to changes than Provençal, where many Latin phenomena were conserved .

In Old French, most of the vowels were front (i.e., not formed in the throat); from the back, only closed and open [o] were present. After the transition of the Latin [u] to the sound [ü], the ordinary [u] did not exist for some time.

But from the end of the 9th century. the Latin sound [l] begins to be vocalized, i.e. turn into a vowel [u] (the transformation of a consonant into a vowel, incredible at first glance, can be visualized by the way small children who cannot pronounce [l] say “uapa” instead of “paw”). So the word alter (Latin - different, different) turns into autre.

In Old French, triphthongs were still fully readable. Let's say they talked about beauty using the word beaus, and not, as it is now (and there is again a vocalized [u], which came from [l]). Interestingly, the phenomenon of vocalization gave us in modern language such pairs of words as belle and beau, nouvelle and nouveau. According to the same scheme of transformation of [l] into [u], the combinations ieu/ueu appeared. Thanks to this, today we have a non-standard formation of the plural of a number of nouns (journal-journaux, animal-animaux, ciel-cieux). Another source of the appearance of the sound [u] was the transformation of the sound [o]: jor ⇒ jur (modern jour, day), tot ⇒ tut (modern tout, everything).

In the XII-XIII centuries. Old French, which had a rich system of diphthongs, is finally losing it. Step by step, ai and ei are contracted into [e], i.e. faire ⇒ fere (business), maistre ⇒ meste (teacher, leader). At the beginning of the 13th century. a new sound [ö] appears in the language as a result of contraction of the diphthongs ue, ou, eu, ueu, and the numeral neuf (nine) is now read as , in the word soul (one, lonely) - respectively. At the same time, nasal (that is, nasal) sounds are fixed in the language (they appeared during the period of folk Latin). The process of nasalization is generally gradual. It is noteworthy that from the 13th century. The nasals an and en are read the same way.

It is interesting that at that time affricates still existed in the language - they can be designated by Russian [ts], [ch], [j] and [dz], but by the end of the 13th century. they are simplified and become, respectively, [s], [w], [g] and [z]. In addition, at a certain period there were two interdental sounds that correspond to the English voiceless and voiced th.

They were designated accordingly: voiceless - th, and voiced - dh, but they were soon lost.

During the Old French period, spelling reflected the actual sound of words. Thanks to this recording, it is possible to trace, among other things, the movement of vowels in diphthongs (ai ⇒ ei ⇒ e). In particular, they wrote: set (modern sept, seven), povre (modern pauvre, poor), etc. However, gradually, with the development of the French language and the French people, with the growth of its self-awareness, culture and history, a romanizing principle of writing appears in orthography, i.e. they tried to reduce the words to the Latin original and use spelling (even if in unreadable letters) to indicate the original basis to which the word went back.

During the same period, in written monuments, at first hesitantly, but still, a function word begins to appear, which poses a big problem for all Russian speakers studying Western European languages. We are talking about the article (in Latin itself - at least in classical Latin - there were no articles!). And while there is no single form for all dialects, no forms of the partial article, and its use is not clearly regulated, this “word” will no longer leave the language!

In the Old French period, the two-case declension system became obsolete. At the same time, it is interesting to note: the forms of the nominative and oblique cases sometimes gave rise to words, albeit similar to hearing, but often with different semantic or stylistic connotations. Modern language words: gars and garçon; copain and compagnon - in Old French, both pairs were forms of the nominative and oblique cases, respectively.

The system of verbal conjugation in writing was very similar to that which exists in the modern language - with the only difference that at first all endings of personal forms were read. This made it possible to construct impersonal one-part sentences without a subject pronoun. For example, this is what the conjugation of the regular verb porter looked like:

However, from the end of the 11th century. t disappears after the vowel (this principle affected not only verbs), and from the end of the 13th century. The pronunciation of s also became optional, which is why the forms of the 1st and 2nd persons coincided, they simply began to end in –e, and then this –e penetrated into the 1st person singular (this is how we got the modern spelling je porte), thanks to which the forms je, tu and il began to be pronounced the same. These changes have not yet affected the plural number of verbs, so for forms with “living” endings it was allowed to construct a sentence without a subject pronoun.

It is interesting that verbs that today belong to group II (of the finir type) had the ending s in all persons:

|

nous fini-ss-on |

|

Today, as is known, the suffix iss is pronounced as much in plural forms.

The third group of verbs even then united heterogeneous verbs that originated in various conjugation paradigms of the Latin language or folk Latin. Since then, this group has not been replenished.

With the development of the language, Old French literature began to appear. One of the most significant works is “The Song of Roland”. In the 12th century. courtly literature and poetry are born (by the way, it is most often possible to determine how a particular combination of letters was read in ancient times by a poetic monument, more specifically, by rhyme - what is associated with what; works on language with transcription appeared much later). However, as a business language, Old French is coming into use slowly, and it is used in parallel, and certainly not instead of Latin.

Middle French period (XIV-XV centuries)

Since the 14th century in France, after a period of fragmentation, monarchical power is strengthened and the royal lands - Paris, together with the Ile-de-France region - become the economic and political center. Because of this, the French (Parisian) variant begins to occupy a leading position in the set of dialects. At the same time, the scope of use of the language noticeably expanded: in the Middle French period, new works of literature appeared - drama, morally descriptive novels, and there was a flourishing of lyric poetry, which was represented both by the works of court poets and by examples of folk art. Spoken French is increasingly penetrating into the official environment of the state - parliament meetings are held in it, and it is used in the royal office. However, Latin did not want to give up its position, in particular, official decisions were still based on it. In the XIV-XV centuries. translation into French of works by ancient authors begins, which revealed the absence of certain terms and contributed to the formation of new words in the national language. The successes of France in the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) only further strengthened the state. The political and territorial unification of the country was finally completed under Louis XI (1461-1483, from the Valois dynasty), after which royal power continued to strengthen.

In phonetics, during this period there is a weakening and loss of unstressed vowels. So seur turns into sur (modern sûr - confident), and the word “August” has lost the initial letter “a”: the folk Latin has decreased to (modern août, the first letter is not readable, but written). The weak e, located in a word between consonants, also begins to disappear (contrerole –> controle - modern control). However, this unstable sound turned out to be tenacious. It began to behave like a chameleon: in some places it persisted, returned, and over time began to be pronounced as [ə] and so has survived to this day - now we know it as a dropped e [ə], for example, in the word carrefour (crossroads) or in the name Madelaine (Madeleine).

At the same time (in the XIV-XV centuries) the French stopped pronouncing the sound [r] in endings -er. This principle applies mainly to long words. This selectivity has continued today (let me remind you that -er is still read here and there in a number of short words, such as mer (sea), hier (yesterday), etc.). One explanation is that [r] is awkward to pronounce after a closed [e], whereas in monosyllabic lexemes [ɛ] is always open.

In the Middle French period, the final formation of nasal vowels took place: they absorbed the consonants –n and –m located after them (previously, the pronunciation of nasals was similar to the English endings –ing, i.e. the consonants –n and –m could be heard). The Old French diphthong –oi, which was read like this: , is now pronounced as [ɛ] or , i.e. the transcription of the word moi became not what it was before, but or.

This sound will change during the New French period.

In general, throughout the history of France until modern times, voices were constantly heard that French was the wrong Latin. During the formation of the state (Gallo-Romans, Germans, feudal fragmentation), the language became clogged. And now, when the new nation has strengthened, it is necessary to create its own, “correct” language. But no one fully knew where this correctness lay. Not many people in medieval France knew how to read and write, but the written language was recorded either in office work or in books, which were rarely published at that time.

In short, everyone wrote as they saw fit, and what was written down on paper was in fact the norm.

In the Middle French period, further ordering of article forms occurs. In particular, the combined form was given by the combination of the masculine singular definite article le and the preposition de. And until the XIV century.

the continuous form del was used (as in Spanish), but now it was transformed into du (remember the vocalization l), as in the modern language (the form dou was also found). A merged form with a definite article was also given by the preposition en - in the singular: en + le = eu (or ou); in the plural - en + les = es. In modern language, the preposition en does not give fused forms, and the forms au and aux are now considered as a merger of the preposition à with the masculine definite article le or the plural les.

In texts of the Middle French period, along with the singular indefinite article un/une, the form des for the plural begins to appear. At first it is often replaced and alternates with the preposition de.

From the 16th century French becomes the main means of communication in the state. In 1539, King Francis I (1515-1547) signed a decree - the Ordonnance of Villers-Cotterêts, which prescribed the use of French in office work and the official sphere. This decision not only consolidated the departure from Latin, but contributed to the further consolidation of the linguistic variant of the royal capital - Paris and Ile-de-France - thus dealing a serious blow to regional dialects.

The changing role of the French language again raised the question of developing canonical norms. “Conservative” grammarians still considered the language of France as a spoiled Latin, but gradually linguists came to the conclusion that it was impossible to return the existing dialect to Latin, and the main task was to enrich and develop the already established language. Proof of its high level of syntactic and lexical coherence can be seen in the fact that in the middle of the 16th century. The most famous work of French literature appears, “Gargantua and Pantagruel” by Francois Rabelais.

The most important phonetic change of the 16th century. can be called a transition to phrasal stress (words merged into one phrase in meaning, and the emphasis was placed only on the main word). Within the framework of this continuous phrase, a phenomenon appears that we now call “ligament” (unreadable consonants at the end of words now seemed to be in the middle and “came to life,” i.e., began to be read (cf. modern vous êtes, where the copula between words gives the sound [z]).

The diphthongs and triphthongs are finally contracted, thanks to which the words acquire their modern phonetic form. Interestingly, the French language has the word château (castle), which probably combines all the phonetic transformations that occurred in French. It was originally the Latin word castellum (castella). During the period of folk Latin, it lost s in the position before the consonant (a circumflex, or “house”, was drawn above the front vowel), before the front-lingual sound [a], the consonant [k] was transformed into [h], then this affricate was simplified to [w], then, during vocalization, [l] turned into [u], which is why the triphthong eua was formed at the end, then it turned into the triphthong eau and contracted into the monophthong [o]: castella -> câtella -> châtella -> châteua -> château. According to the same scheme camel -> chameau (camel), alter -> autre (other, different) were transformed.

In the modern French period, the conversation about spelling continues. A number of well-known linguists expressed an opinion on the need to bring spelling and pronunciation closer together, but the majority remained conservatives. One of the arguments (which, by the way, was also guided by the tsarist government in Russia when the issue of abolishing the letter “yat” was discussed) was this: spelling can distinguish a commoner from an educated person. In addition, the French language, which had already undergone a number of phonetic movements, lacked graphic signs to represent sounds. ![]() Not everyone knows that in the Latin alphabet, since Roman times, for a long time the letters V and U were not distinguished in writing. Now this seems incredible, because everyone can see that the “V” has a pointed squiggle, and the “U” has a smooth one, but Such a simple solution did not come immediately. And to distinguish the sounds [v] and [u] in writing, they came up with some tricks, in particular, if it was the sound [u], then after this most unstable grapheme they also wrote the letter l (since it itself was vocalized in a number of words and also gave the sound [u]) - and so we got Renauld.

Not everyone knows that in the Latin alphabet, since Roman times, for a long time the letters V and U were not distinguished in writing. Now this seems incredible, because everyone can see that the “V” has a pointed squiggle, and the “U” has a smooth one, but Such a simple solution did not come immediately. And to distinguish the sounds [v] and [u] in writing, they came up with some tricks, in particular, if it was the sound [u], then after this most unstable grapheme they also wrote the letter l (since it itself was vocalized in a number of words and also gave the sound [u]) - and so we got Renauld.

In the middle of the 16th century. to denote the sound [s], another letter was borrowed from Spanish - ç (by the way, the inventors of this letter, the Spaniards, quickly abandoned it, but it has taken root in French).

In the New French period, the formation of the article system was completed, and it acquired its modern form. In addition, in vocabulary and spelling, a distinction is made between masculine nouns (which have a zero ending) and feminine ones (which have an e ending, which is still poorly read). A system of independent personal pronouns (moi, toi, etc.) is finally formed, and the forms are je, tu, etc. can no longer be used without a verb. The formation of a number of possessive adjectives is completed, and we can rightfully sing a song about mon-ma-mes, ton-ta-tes...

In the 16th century the endings of verbs in the forms I, you, he/she, they finally and irrevocably die out (linguists did not dare to remove them from spelling, again acting within the framework of the historical principle - etymology and relatedness of word forms). This forever excluded the possibility of constructing impersonal sentences with one predicate, since without a subject it is not clear who or what is performing the action. As a result, the language acquired one of the most important features of the analytical system - a fixed word order in a sentence.

A lyrical digression - about analytical and synthetic languages.

There are synthetic languages, where the function of words in a sentence is expressed by changing the word itself (adding or truncation of endings, prefixes, etc.) and analytical, where function words (prepositions or auxiliary verbs, as well as the very arrangement of words) are unique markers.

In practice, it can be described as follows: in a sentence there is always a subject, which performs the action, and an object, which is the object of the action. The most important thing to understand is to determine who is who. In Russian, which is a synthetic language, the main indicator is the case: if it is nominative, then it is the subject, if indirect it is the object (let’s say that 5 indirect cases allow us to more accurately express the nature of the object). Another indicator is the number, which agrees with the verb (and it becomes clear who performs the action), gender, as well as rich verbal inflection (when each person and number has its own unique form). The second task in the sentence is to determine where whose definition is, because. both a subject noun and an object noun can have an attributive adjective. “Synchronization” in case, number and gender of adjectives and nouns allows us to figure this out. The main advantage of such a system is the possibility of free word order, because we will still determine who is who using the algorithm described above.

The main disadvantage is that you have to constantly change words with precision, literally go inside the word, and speakers don’t really like this. Remember how difficult it is for many people to declension of numerals, because... they are used less often than nouns, and the paradigm of their declension is more complex than usual.

A distinctive feature of the French language is also the fact that even the number of a noun (with rare exceptions) is expressed using external attributes - articles. In other words, a noun depends on who surrounds it. Among the disadvantages of this system are a clear word order (you cannot deviate), the impossibility of one-part - impersonal - sentences, inversions; in terms of understanding, you always need to hear the entire sentence or phrase. Among the advantages is the ease of constructing sentences: there is no need to go inside the words, you just need to add one “cube” next to it.

The question of uniform norms of written and oral language arose again at the beginning of the 17th century. The establishment of absolutism became a new milestone in the development of France. Royal power concentrates political and economic potential in its hands; a single language is perceived as an integral part of the state machine. In 1636, on the initiative of Cardinal Richelieu (the one who plotted d’Artagnan), the French Academy was formed, designed to regulate issues of the national language. It included conservative representatives of Parisian society who believed that the language should be freed from “pollution” - i.e. vernacular. The principle of correct usage (bon usage) was also emphasized by the purist Claude Vaugelas (author of the rule of the same name, which requires replacing the article des with de if the adjective comes before a plural noun).

Changes in phonetics continue. In the middle of the 18th century. the combination oi (let me remind you that in Old French it was pronounced as and then turned into the sounds [ɛ] or, depending on the dialect) begins to transform into . At first it was considered colloquial, but then it became firmly established in the language. Thus, the executed queen of France became Antoinette (and not Antenette), and the pronoun moi became , not .

The transformation did not affect only a number of words where, as before, they said [ɛ], and there they simply changed the spelling (replacing oi with ai): françois -> français, foible -> faible, the old [ɛ] is also retained by the second largest ( after Paris) the French-speaking city of the world is Montreal. It received its name from the royal mountain on which it is said to be located, and according to the old pronunciation royal was read as . After phonetic changes, the mountain began to be called Monroyal, but by that time they had already gotten used to the name of the city and decided not to change it.

In the 18th century The unstable sound [ə] continues to transform. As in modern language, it is no longer pronounced at the end, but in the middle it still exists and in some places is replaced by é (décevoir - to disappoint). The system of nasal vowels is being streamlined - in particular, according to the new rule, if a vowel is closed by a pronounced nasalizing consonant, then the sound remains clear. In modern phonetics we know this, as a rule, that a sound remains clear when it is followed by "nn" or "mm".

In XVII-XVIII, the disappearance of endings continues, but later we will see how, for the first time in history, letters were made to be read again! But first things first.

In addition, the French began to “drop” the [k] in the word avec from time to time. The loss of consonants would have continued, but linguists intervened. In the word avec, the pronunciation of the last letter was mandatory. Also, thanks to the “volitional decision”, final –r in verbs of group II and words in -eur began to be read again. In addition, we restored the pronunciation of the sound [s] in the words piusque (since), presque (almost) (once upon a time they were formed by merging puis+que and près+que, respectively, and, as is known, s in the position before a consonant was not read from the 13th century). After all, the Richelieu Academy did its job! Even if not very consistently.

In the XVII-XVIII centuries. palatalized sound, which is expressed in writing as ill(e) and was previously pronounced as Italian gli or classical Spanish ll (in Russian the sound is rendered as [l], for example, in the word Seville), transformed into [th] (which is considered a further degree palatalization of the already soft [l]) and acquired its modern sound. Exceptions, as you know, are mille, ville, tranquille, as well as the city of Lille.

It can be especially noted that over the last 2-3 centuries, a number of French tenses (complex in structure) cease to be used in colloquial speech. In particular, the Passé Composé form has practically supplanted the Passé Simple, and in the speech of native speakers the principle of tense coordination is little observed (which again requires the use of complex, compound relative tenses).

This is how the French language acquired its current phonetic and grammatical structure. However, human speech is a very living tissue, so new changes will not keep you waiting. And as we master the language, we will begin to notice them ourselves.

This article has an author, Artem Chumakov. Here is his page on Google+. Copying the text of the article is possible only with his consent!This article uses photographs from Wikimedia Commons, as well as photographs produced by the author of this site. If you would like to use these photos please check out

Gallo-Romance language The Gauls were a small part of the Celts. Before the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (58-52 BC), their language was the main one. Modern French retains a few Gaulish nouns, mostly relating to rural life ( chemin - road, dune - dune, glaise - clay, lande

- lands...).

The Latin language, which the Gauls mastered by constantly communicating with Roman soldiers and officials, gradually changed and was called folk Latin, or the Romance language.

France took its name from the Franks, the last conquerors of Germanic origin. But they did not have a strong influence on the language.

What remains from them are words related to the war ( blesser- to injure, guerre- war, guetter- guard, hache- ax,..), feelings associated with it ( haïr- to hate, honte- shame, orgueil- pride...), as well as to agriculture ( gerbe- bouquet, haie- hedge, jardin- garden...).

Old French and Middle French

The Romance language was divided into dialects: northern- he was influenced by the Franks (“ oui" yes it was pronounced oïl), southern- he was influenced by the Romans (“ oui" yes it was pronounced OS). Starting from the 15th century, all dialects were replaced by French, which was spoken by the inhabitants of Ile-de-France. It lies at the heart of the French language. The Capetians, a dynasty of French kings, were the owners of the Ile-de-France, and Philip Augustus turned Paris into the capital of his state.

Renaissance

As a result of the Italian wars of the late 15th century and the reign of Marie de' Medici, many Italian words related to military affairs appeared in the French language ( alarme- anxiety, embuscade- ambush, escadron-squadron, sentinelle- sentry...) and art ( arcade- arcade, balcony- balcony, sonnet- sonnet, fresque- fresco...).

The French Academy, founded by Richelieu in 1634, was responsible for the regulation of the French language and literary genres.

In 1694, the first academic dictionary was published.

Since 1714, the date of the signing of the Treaty of Rastatt (drawn up in French), French has become the language of international diplomacy.

In the 18th century, the French language was enriched with many English words ( meeting- rally, budget- budget, club-club, humor- humor...).

Changes in pronunciation and spelling

Until the Revolution of 1789, the number of French people who could read and write was small. Spoken French, without having strict rules, changed, in particular, pronunciation changed.

As for spelling, it depended on the printers. Since the written language was not available to the general public, no one bothered to systematize it. After 1789, especially in the 19th century, the number of schools increased. French spelling is becoming a necessary discipline in the school curriculum. Since 1835, the rules of French spelling, as formulated by the Academy, are mandatory throughout the French Republic.